CPS Unit Number 049-01

Camp: 49

Unit ID: 1

Title: Philadelphia State Hospital

Operating agency: AFSC

Opened: 8 1942

Closed: 10 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 187

-

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaCPS man bathing arm of patient, 1943. Ministering to the mentally ill. This is one of 1400 CPS men who are serving in 40 different hospitals throughout the country. CPS attendants work at the humblest of tasks--bathing ulcerated limbs of patients, changing soiled linens, feeding, quieting.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1943

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaCPS man bathing arm of patient, 1943. Ministering to the mentally ill. This is one of 1400 CPS men who are serving in 40 different hospitals throughout the country. CPS attendants work at the humblest of tasks--bathing ulcerated limbs of patients, changing soiled linens, feeding, quieting.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1943 -

CPS Camp # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaPhil Steer, Leonard Edelstein, Willard Hetzel, Harold Barton, founders of the Mental Hygiene Program of the Civilian Public Service and the National Mental Health FoundationDigital image from the Harold Barton Collected Papers (CDGA), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaPhil Steer, Leonard Edelstein, Willard Hetzel, Harold Barton, founders of the Mental Hygiene Program of the Civilian Public Service and the National Mental Health FoundationDigital image from the Harold Barton Collected Papers (CDGA), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

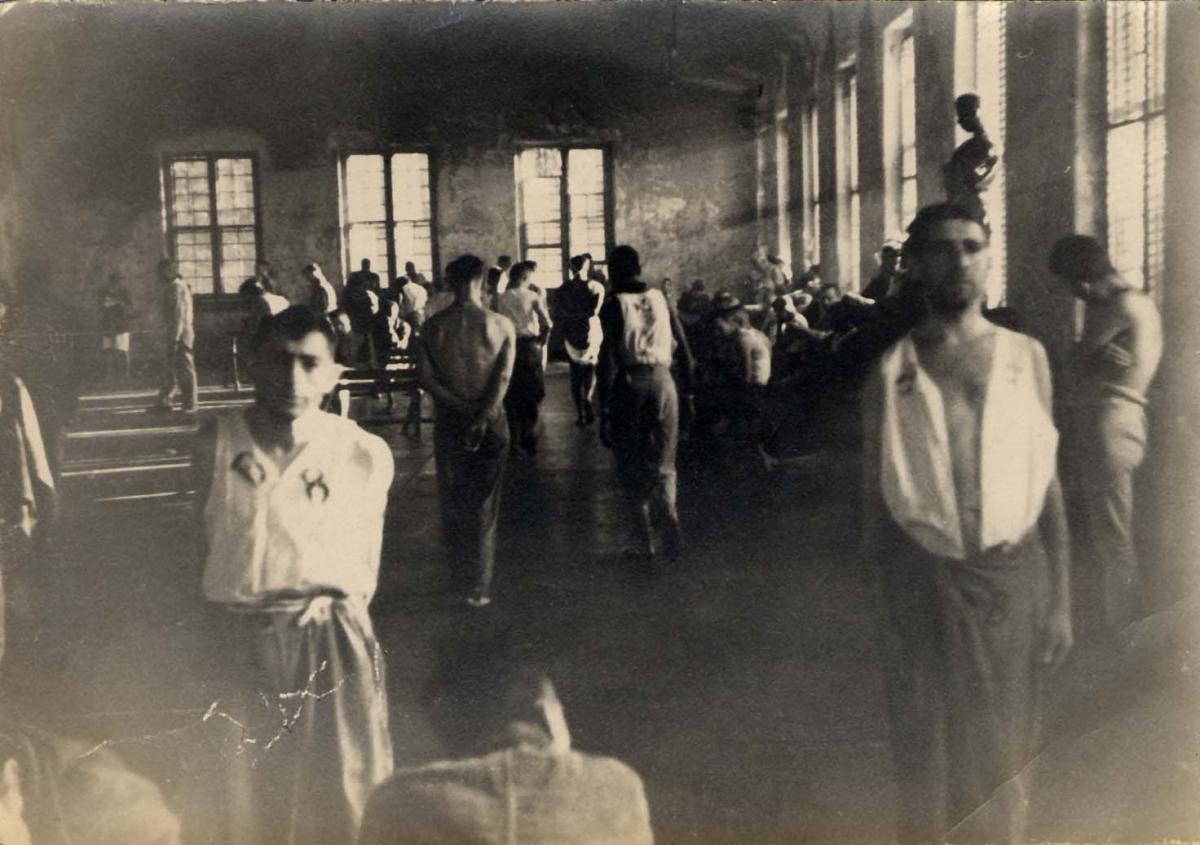

Byberry B Building, Violent Ward Day RoomImage by Charles Lord, from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056) Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

Byberry B Building, Violent Ward Day RoomImage by Charles Lord, from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056) Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

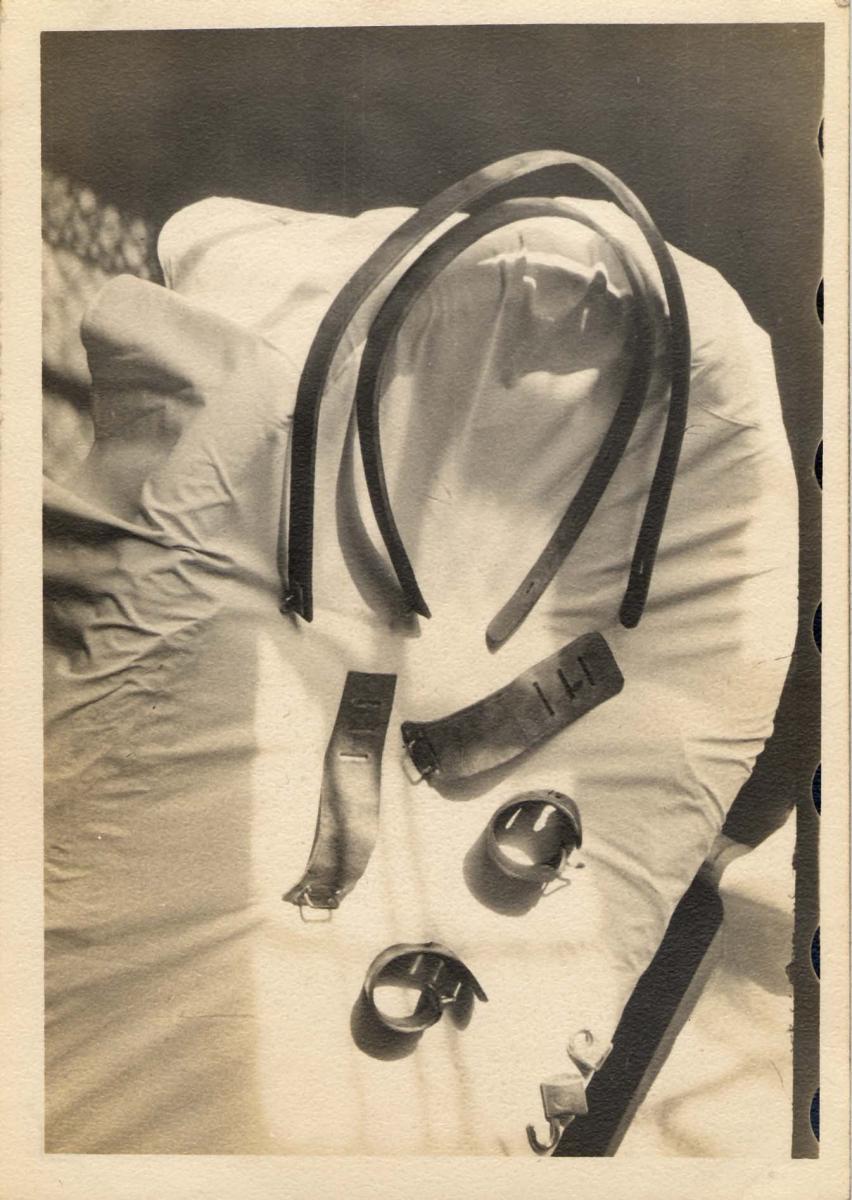

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaRestraintsImage by Charles Lord, from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056) Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaRestraintsImage by Charles Lord, from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056) Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaCPS Annual PicnicDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1944

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaCPS Annual PicnicDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1944 -

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaBarbecueDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1944

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaBarbecueDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1944 -

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaMental Health ClassDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaMental Health ClassDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaJaundice Unit, Shot in armDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaJaundice Unit, Shot in armDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaChorus, Bob Steele conductingDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1944

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaChorus, Bob Steele conductingDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1944 -

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaRadio Program WCPS. Cottage 1, Mrs. L Rankin, D. Perrone, R. Lyon, Phil Steer, D. RiggsDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PennsylvaniaMarch, 1944

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaRadio Program WCPS. Cottage 1, Mrs. L Rankin, D. Perrone, R. Lyon, Phil Steer, D. RiggsDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PennsylvaniaMarch, 1944 -

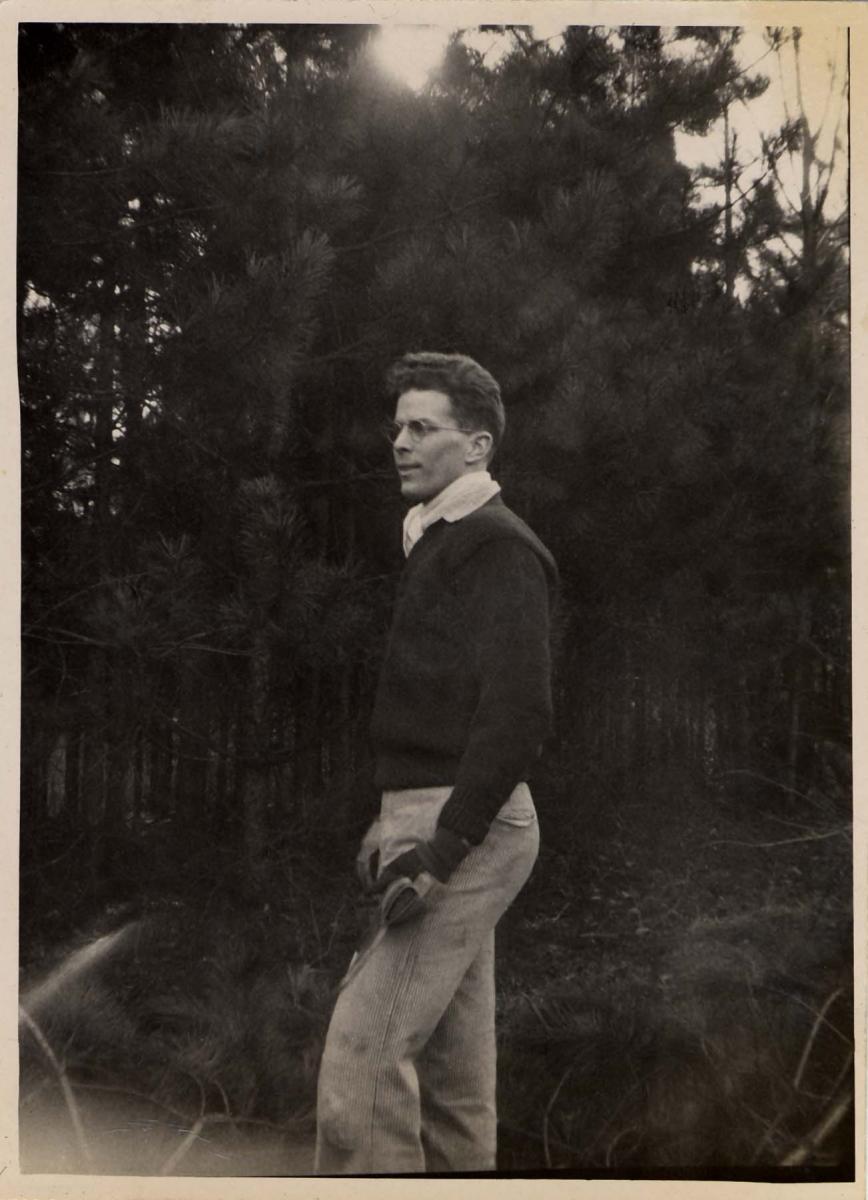

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaWarren SawyerDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PennsylvaniaNovember, 1945

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaWarren SawyerDigital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PennsylvaniaNovember, 1945 -

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaChorus, Summer 1944. Walter Kirk, Tom Riggs, Charlie Lord, Bernard Lehman, Don Riggs, me, Harold Barton, Roy Simon (?), Jane Terhume (?), Marjorie Levissy (?), Ruth Wandt (?), Bob Reuman (?) Bob Steele, Ann Martin, Jean Riggs, Margarette (?) Riggs, Harriet Frakie (?), Edith Farley, Grace G. Riggs, Ruby Kirk, Elann (?)Shrine.Digital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PennsylvaniaSummer, 1944

CPS Unit # 49, Philadelphia State Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaChorus, Summer 1944. Walter Kirk, Tom Riggs, Charlie Lord, Bernard Lehman, Don Riggs, me, Harold Barton, Roy Simon (?), Jane Terhume (?), Marjorie Levissy (?), Ruth Wandt (?), Bob Reuman (?) Bob Steele, Ann Martin, Jean Riggs, Margarette (?) Riggs, Harriet Frakie (?), Edith Farley, Grace G. Riggs, Ruby Kirk, Elann (?)Shrine.Digital Image from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PennsylvaniaSummer, 1944

-

1943

1943 -

-

-

-

1944

1944 -

1944

1944 -

-

-

1944

1944 -

March, 1944

March, 1944 -

November, 1945

November, 1945 -

Summer, 1944

Summer, 1944

CPS Camp No. 49, a mental hospital unit at Philadelphia State Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, opened in August 1942. Known as Byberry, the unit was operated by the American Friends Service Committee until it withdrew from CPS in April 1946. Selective Service operated the unit until it closed in October 1946. Most of the men worked as orderlies and ward attendants.

Philadelphia State Hospital was located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, its patient population about six thousand one hundred. The American Friends Service Committee opened the unit in August 1942.

The city of Philadelphia had run Byberry as the Philadelphia Hospital for Mental Diseases. Investigated by panels and commissions, it was turned over to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and officially named Philadelphia State Hospital in 1938. World War II created severe staff shortages and deteriorated conditions for patients.

Director: Robert Blanc, Giles Zimmerman

Dr. Charles Zeller, Superintendent of Philadelphia State Hospital personally went to CPS Camp No. 23 at Coshocton, Ohio to recruit the first group of COs to work at the hospital. In April 1944, ninety-five men made up the unit at Byberry. Eventually, nearly one hundred and thirty-five comprised the unit. Many were married.

Some wives worked at the hospital for pay. Dr. Zeller worked with AFSC officials to establish a women’s unit at the hospital to address staff shortages in women’s wards. Eight women opened the women’s unit in June 1944. From June 1943 to October 1944, twenty-nine women worked at Byberry. Five were married to Byberry COs, three would marry unit men. Several had started work before the women’s unit was formed. The women included college students, teachers and secretaries. Women were recruited by American Friends Service Committee pamphlets and by word of mouth.

With respect to denominational affiliation, a minority of men in the American Friends Service Committee camps and units when entering CPS reported denominational affiliation with Friends. The Friends camps and units included the most diverse array of religious and philosophical experiences of all the camps and units, including COs with no religious affiliation. At Byberry around August 1944, of one hundred men, twenty-two were Friends, twenty-eight Methodists and eighteen had declared no denominational affiliation when entering CPS. (Taylor p. 181)

Forty-three percent of men in Friends camps reported their occupation as technical or professional when entering CPS. This was more than double that of men in Brethren and Mennonite camps. On average, the men had completed 14.27 years of education when entering CPS, with sixty-eight percent having completed some college, having graduated or completed postgraduate work. (Sibley and Jacob, pp. 171-72) They more frequently arrived from urban rather than rural areas of the country.

Of the women, eight identified Friends affiliation, while others reported Methodist, Episcopal, Lutheran or other denominational affiliations.

Conscientious objectors worked as orderlies, ward attendants and technical or support staff. At the time the CPS unit was established, Byberry had one hundred ten vacancies in a male attendant staff of one hundred seventy-three positions. According to Charles Zeller, Superintendent of the hospital, the ratio of attendant to patients was one attendant per shift for one hundred forty-four patients. After the COs arrived usually one to four attendants worked with three hundred fifty patients in the “violent” building. When the unit grew to nearly one hundred thirty-five COs, usually six to seven attendants worked during the early day shift in that ward, while five attendants staffed the 2 pm to 11 pm shift. More than three hundred patients in some of the buildings spent their days in rooms forty feet by seventy feet.

The hospital paid COs room, board, laundry, and a personal maintenance fee, originally $2.50 per month. That was later increased to $10-15 per month.

For the women’s wards, staff shortages were even more severe. One attendant staffed a two-story building housing two hundred forty-three patients; two attendants covered the first shift of a semi-violent ward of over two hundred fifty patients, and only one attendant staffed each of the second and third shifts.

Women attendants worked for $66.50 per month, plus room and board, including laundry for a fifty-four hour work week. CPS wives received that wage as they were not subject to Selective Service regulations.

Both the men and the women reported receiving some training, although not before they began their work as attendants. Orientation by the nurse on the women’s ward was described as “useless” by Alice Calder; as “no real preparation for our work as attendants” by Lois Barton. Classes on mental illness and therapies were offered. Hal Barton reported, “It was over a month before I received an orientation or training course planned by the hospital for new employees”. (Taylor pp. 201, 229) Hal Barton went on to say,

We were presented with the latest insights into the nature, the care, the treatment of mental illness. Our instruction was on a high and idealistic level. The contrast between the ideal and the practical day-to-day ward situation was so striking as to be upsetting to say the least. (Taylor p. 202)

The men lived in dormitories in former patient cottages. Men slept in bunk beds placed about eighteen inches apart, and used lockers in a separate cramped room for their personal belongings.

Women lived in the Female Attendants’ Home along with regular employees.

Some COs at Byberry helped form a CPS union. They addressed a number of issues, including employment of African Americans as attendants. Superintendant Zeller was favorable toward introducing “colored employees into the wards” as part of a CPS unit, but not as regular attendants due to prevailing attitudes among regular employees. COs anticipated the kinds of issues they would need to address should an African American be assigned to the unit, in their commitment to help that person do a good job as attendant. CO Warren Sawyer wrote that the first black CO arrived at the mental hospital in February 1945. When interviewed in 2007, he did not recall any problems or incidents. (Taylor p. 100-01)

With overcrowding of patients and staff shortages, the unit men and women ward attendants experienced shock and depression over the conditions for patients. They changed much soiled clothing and bedding, bathed, shaved and fed patients, attempted to control violent patients, keep them from harming themselves or others, and even prepared dead bodies for the morgue.

The quality of attendant care varied greatly. At Byberry, some tried to do a conscientious job even though attitudes and methods seemed outdated and harsh. An exceptional attendant in A Building modeled the care patients deserved, but he was viewed as a rare exception. Other attendants were themselves outcasts, some transients and drifters, and used to violence as a way of resolving difficulties with others.

A Building was known for its incontinent patients with its accompanying stench. Patients suffered lesions, lice and other health problems. B Building, often in disrepair, housed the “violent” ward, where gangs struggled for control with weapons, including razors and knives. Patients often responded with predictable behaviors in reaction to the conditions of the institutions themselves. Regular attendants used clubs, or a hose filled with buckshot to beat difficult patients. Some patients were required to do the dirtiest of work in both men’s and women’s wards. Pacifists struggled to find non-violent methods to bring patients under control.

The COs generally tried to avoid the use of force with patients, even when challenged by blows from patients. They also tried to limit use of physical restraints—cuffs, straps and straightjackets. When COs were provoked or lost control with a difficult patient they felt badly. Some COs were not suited for work in the wards.

“Philadelphia State Hospital, Byberry, was the birthplace of the national movement to reform state mental hospitals and training schools through the Mental Hygiene Program of the CPS and then the National Mental Health Foundation.” (Taylor p. 260) COs collected reports of abuses and conditions at state mental hospitals and training schools for years.

Four COs created the national movement, forcing the National Committee for Mental Hygiene and the American Psychiatric Association to take note of conditions and address them. Len Edelstein and Phil Steer from upstate New York held undergraduate degrees from Syracuse University. Will Hetzel, a lawyer and Hal Barton, a mining engineer prior to CPS joined the effort. All were appalled at the conditions. Hetzel came from Cleveland State Hospital where he had given an account of abuses there for the report that began to expose conditions. Steer, after a month on the wards, transferred to a clerical position. Edelstein started a recreational program for patients in his off-duty hours. Barton worked in the “violent” B Building.

Barton and Edelstein believed that the men were not using their experiences enough to address conditions for patients. Barton focused on exposing conditions at Byberry, by gathering statements from COs. In conversations among the four men, they began to plan how they might contact COs at other hospitals and collect reports to be used in a Summary Statement. The four engaged other interested men and women in the CPS unit at Byberry to work with them.

In March 1944 Edelstein attended the AFSC meeting of mental hospital and training school personnel directors, raising the idea of having the Byberry unit take responsibility for coordinating activities and communications among the various units. The personnel directors expressed support.

Edelstein contacted Superintendent Charles Zeller about the idea, since Zeller had welcomed the CO effort to raise awareness of mental hospital conditions and the need for change. He approved the creation of a mental hygiene program as long as the COs agreed not to try to expose individual mental hospitals or officials. He made an office available for CO use in off-duty hours and put them in contact with reformist psychiatrists and mental hygiene leaders.

Paul Furnas of AFSC provided a monthly $80 stipend that included $10 for expenses associated with a summary and $70 for a newsletter. The Mental Hygiene Program was established in May 1944, Edelstein as coordinator with Steer responsible for publications focused on an inter-unit newsletter, and Barton responsible for a “Summary Statement of Conditions” at mental hospitals and training schools. Hetzel joined the program later.

The Summary Statement would later become Out of Sight, Out of Mind, compiled by Frank Wright and published three years after the initial call for reports.

The first issue of the Mental Hygiene Program’s inter-unit publication The Attendant appeared in June 1944 with a feature article by George S. Stevenson, medical director of the National Committee for Mental Hygiene. It attracted favorable attention from Eleanor Roosevelt and Paul Comly French of the National Service Board for Religious Objectors, who discussed it with Colonel Kosch and Mr. Imrie of Selective Service, both of whom felt it would serve extremely useful purposes. The work begun at Byberry would end up being instrumental in not only calling attention to inhumane conditions in the mental hospitals and training schools, but also generating the public support and awareness that would help convert custodial care to mental health care.

Zeller not only appreciated the work of the COs, but also served as an adviser to, and strong supporter of men who started the Mental Hygiene Program. He believed that an exposé should not be focused on individual institutions, but rather unveil the data COs had been collecting from mental institutions across the country.

The goal of the COs was to rally support through exposing conditions so that state legislators would fund the institutions and urge reform. By early 1946, Zeller had announced his resignation and a pending move to direct Michigan’s newly formed Department of Mental Health.

On Sunday February 10, 1946, the Philadelphia Record carried a front-page article headlined “Head of Byberry Says B Still is Disgrace: Dank, Overcrowded Building Gets Dregs of Mental Cases”, including Zeller’s candid appraisal. COs wrote letters to the editor and one wrote letters for relatives of patients to sign when they visited.

S. M. R. O’Hara, Secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Welfare, visited Byberry to inspect Building B. She was critical of the COs for writing letters rather than cleaning up the wards on their own.

In mid-April, Deutsch published a series of articles in the magazine PM which appeared a week before the exposé at Cleveland State Hospital. Less than three weeks later, Maisel published his exposé of conditions in state mental hospitals in Life Magazine, “BEDLAM, 1946: Most Mental Hospitals Are a Shame and Disgrace”. The feature included photographs of Byberry patients with the captions “Idleness”, “Nakedness” and “Crowding”. (See article here: Bedlam 1946)

Even then O’Hara and the Republican governor Edwin Martin denounced the articles as prejudicial. O’Hara took aim at the National Mental Health Foundation, just established by the Byberry COs. She accused them of presenting a distorted picture of Byberry and she wrote the foundation in dispute of its account.

Hal Barton responded to O’Hara on behalf of the Foundation, summarizing the efforts by superintendents to secure funding to improve facilities and staffing, with negative results. The Foundation believed that if citizens knew the effects of neglect and lack of support, then states would no longer withhold support. He then asked that O’Hara forward plans from her department for remedying the difficult personnel situation and the manner “to achieve a human standard of care and an enlightened standard of treatment for the mentally ill”.

The Governor made a well publicized tour of Byberry; O’Hara, to save face, came out with her own report; Pennsylvania advocated $80 million for new mental hospital construction the following year. Zeller was unscathed by the reports and retained his reputation as a public official who acknowledged the failings of the institution.

With Life Magazine’s wide circulation, readers began to connect the exposé of inhumane conditions with the honesty and sincerity of COs, who, through their service in mental hospitals were “doing work of national importance” that would have lasting value for the country.

A group of the Byberry COs participated in jaundice experiments at the University of Pennsylvania as part of CPS Unit No. 140, (previously CPS Unit No. 115 under the Office of Scientific Research and Development). The experiments grew out of problems during the war, particularly in Italy where more men contracted hepatitis than were killed or wounded in combat. Superintendent Zeller supported their participation. The Office of Surgeon General, the American Friend Service Committee and the Brethren Service Committee sponsored the hepatitis experiments. Other volunteers in the experiment lived in the CPS quarters at Byberry or in a former fraternity house on the University of Pennsylvania campus.

Some men participated since “it got them away from Byberry”; others because they believed the experience to be an opportunity “to serve mankind”. Neil Hartman’s reason for participation reflected another motivation: “We were called yellow bellies and things like that. I wanted to prove that I wasn’t afraid to take risks if it did good. I would not take risks to kill people, but if it would save people. . . . Actually I was happy that I had the opportunity to show the world I was willing to take risks”. (from 2007 interview reported in Taylor p. 85.)

The Byberry COs, well known at local Friends meetings, participated in educational and social activities.

The men published an inter-unit camp paper called The Attendant which reported on abuses in mental health units. Volumes 1 No. 1 through Volume 2 No. 12 (June 1944 – December 1945) are archived in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection on CPS. The men also published a unit paper The Dope Sheet from July 1944 through April 1946, also archived in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection on Civilian Public Service.

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

For stories from men who, as COs, walked to a different drummer during World War II, see Mary R. Hopkins, Editor, Men of Peace: World War II Conscientious Objectors. Caye Caulker, Belize: Producciones de le Hamaca, 2010, John Bartholomew pp. 79-84; Neil H. Hartman pp. 178-184; Warren D. Sawyer pp. 32-44.

For general information on CPS see Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 1990.

See Albert Q. Maisel, “Bedlam 1946: Most U.S. Mental Hospitals are a Shame and a Disgrace,” Life (May 6, 1946), 102-118.

See also Alex Sareyan, The Turning Point: How Persons of Conscience Brought About Major Change in the Care of America’s Mentally Ill. by Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1994, including Chapter 3, A View from the Lion’s Den, a collection of excerpts from Warren Sawyer’s letters about his service at Byberry, pp. 37-58.

For an in depth history of conscientious objection in the United States, see Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-1947. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.

For more in depth treatment of mental health and training school units, see Steven J. Taylor, Acts of Conscience: World War II, Mental Institutions, and Religious Objectors. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2009. For the impact of the Life Magazine expose on the appreciation of CO work, see in particular pp. 290-95.