CPS Unit Number 108-01

Camp: 108

Unit ID: 1

Operating agency: AFSC

Opened: 6 1943

Closed: 12 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 515

-

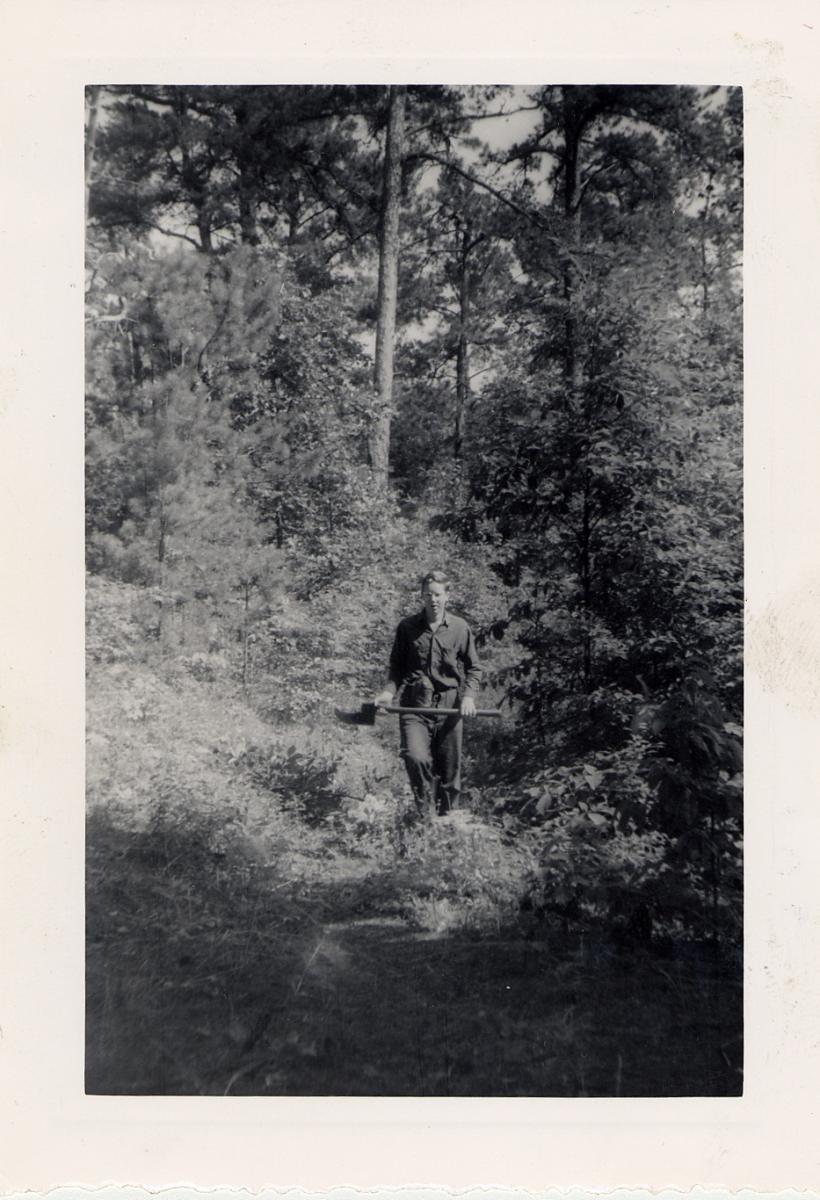

CPS Camp No. 108, Gatlinburg, TennesseeJack Wright cutting firewoodDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945

CPS Camp No. 108, Gatlinburg, TennesseeJack Wright cutting firewoodDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945 -

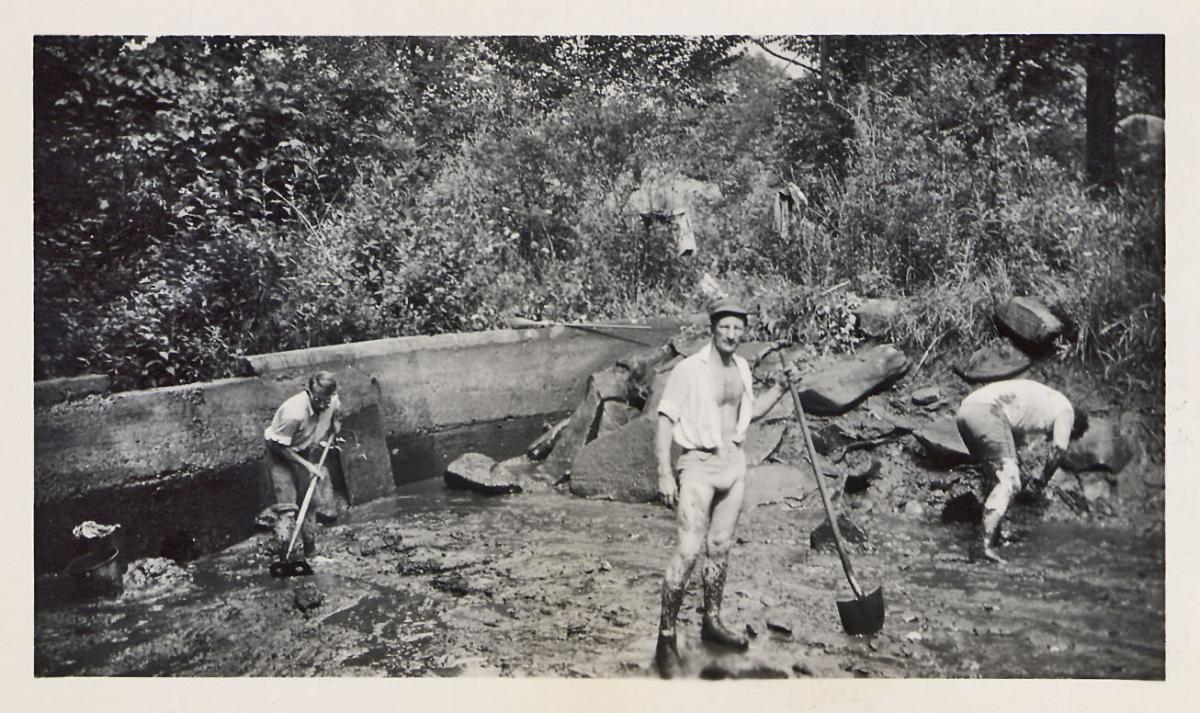

CPS Camp No. 108, Gatlinburg, TennesseeJ. Wasched, C. Fenton and G. Fosch cleaning water reservoirDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 108, Gatlinburg, TennesseeJ. Wasched, C. Fenton and G. Fosch cleaning water reservoirDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

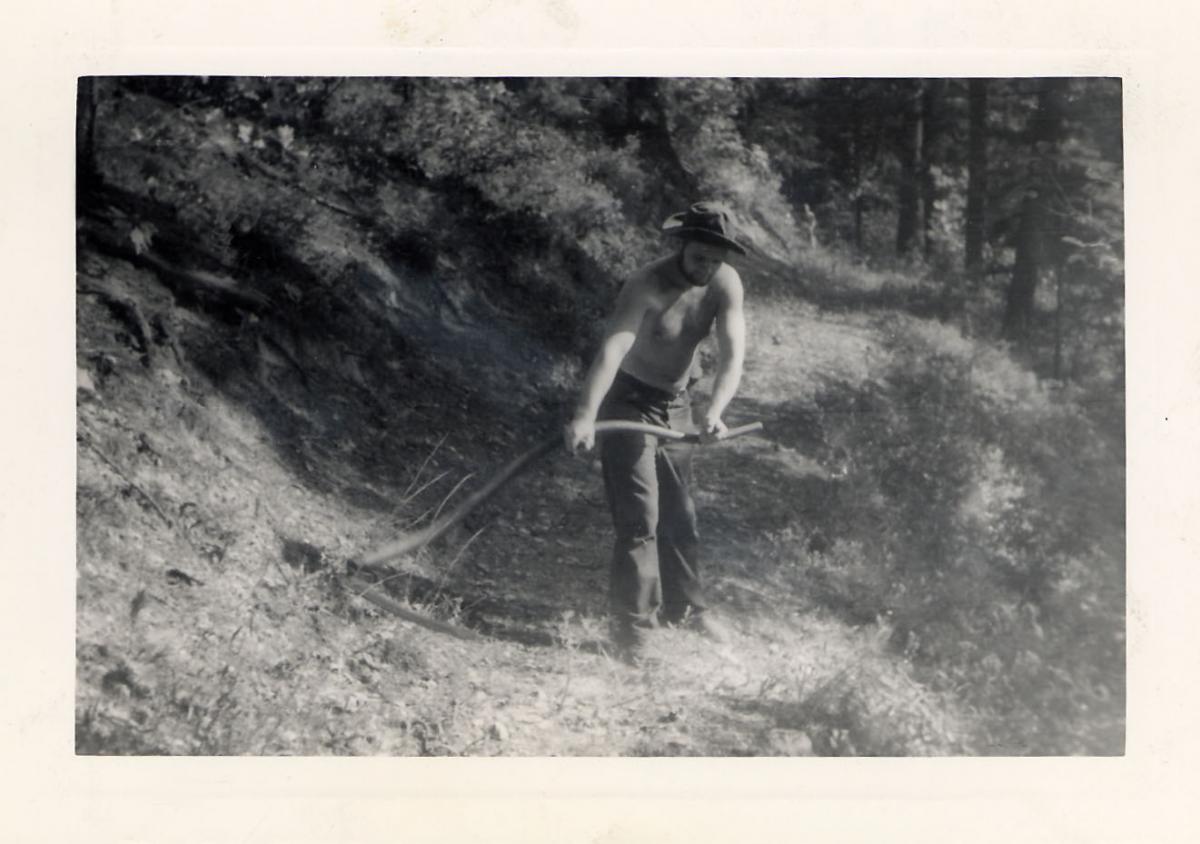

CPS Camp No. 108, Gatlinburg, TennesseeFrank Miles clearing trailDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 108, Gatlinburg, TennesseeFrank Miles clearing trailDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

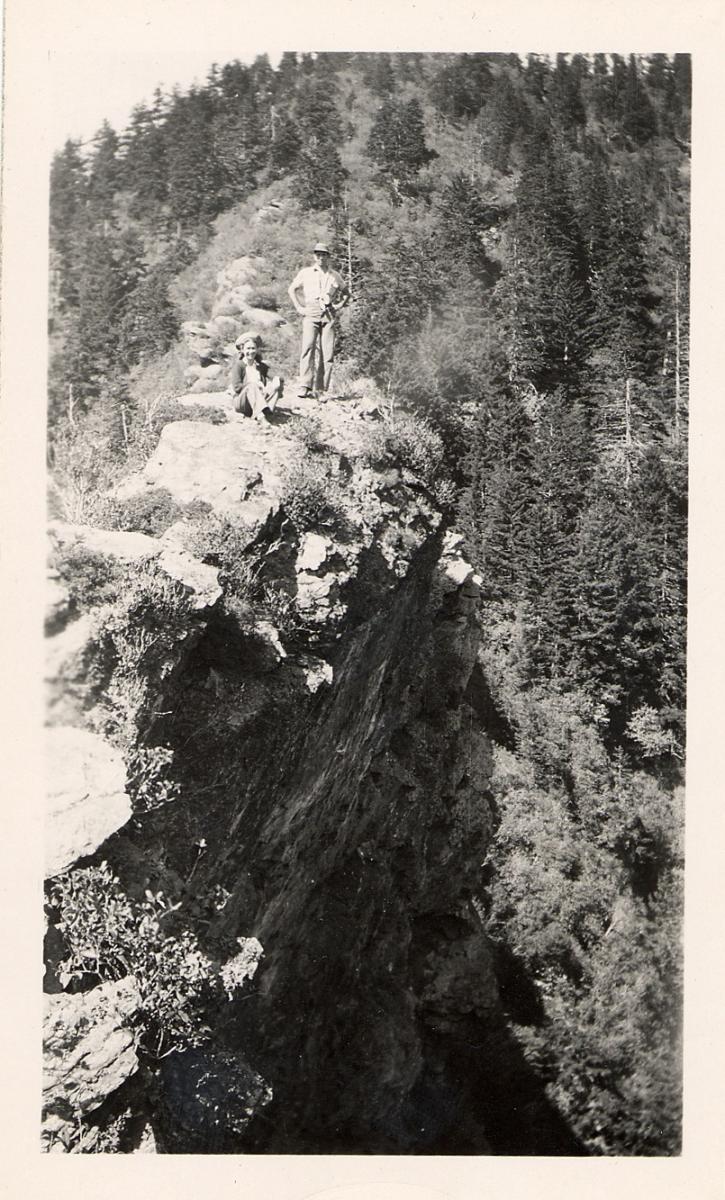

CPS Camp No. 108Unknown and Ralph Garrett atop Peregrin Ridge.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 108Unknown and Ralph Garrett atop Peregrin Ridge.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

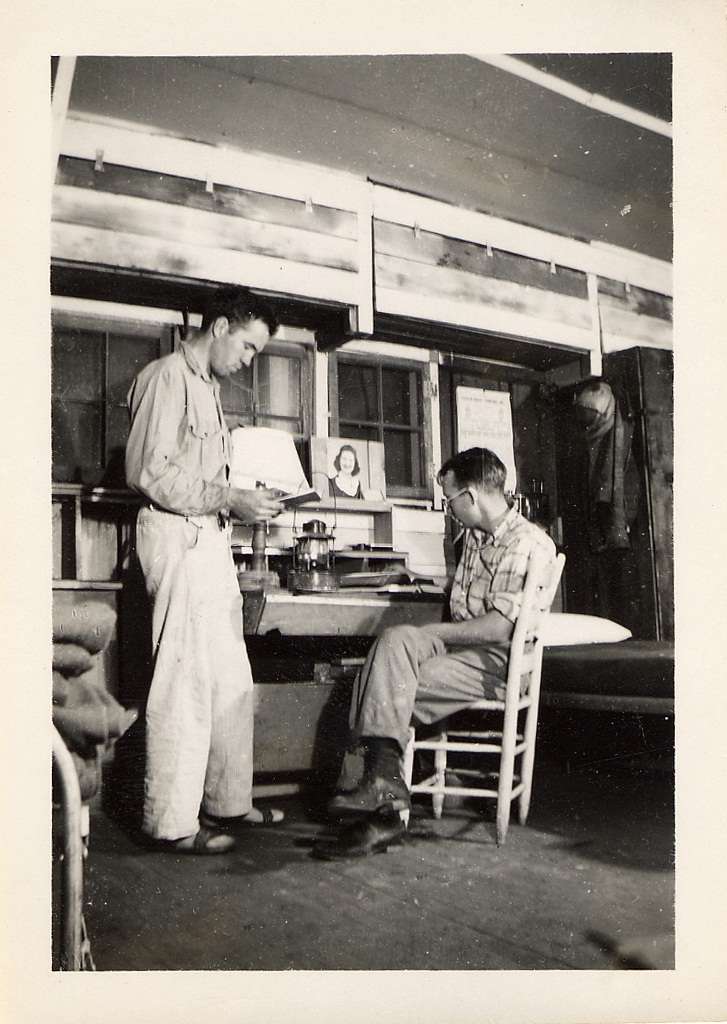

CPS Camp No. 108Bill Newlin and John Washeck in the dorm.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 108Bill Newlin and John Washeck in the dorm.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 108Cassius Fenton in the camp office.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 108Cassius Fenton in the camp office.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 108Ed Nicholson clearing trail.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 108Ed Nicholson clearing trail.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 108Lloyd Massey, Jacob Rudisill, Green, Joseph Allred, Oliver Horn making signs for park use.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 108Lloyd Massey, Jacob Rudisill, Green, Joseph Allred, Oliver Horn making signs for park use.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 108, a National Park Service camp located near Gatlinburg, Tennessee and operated by the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), opened in June 1943. When the AFSC withdrew from the CPS Program in March 1946, Selective Service operated the camp until it closed in December 1946. Men in the unit fought fires, repaired trails, maintained roads as well as other duties. The men organized a School of Race Relations at the camp.

This National Park Service camp located near Gatlinburg, Tennessee was also referred to as Camp Rufus Jones, named after one of the founders of the American Friends Service Committee.

Directors: Raymond Binford, John Ferguson, Felix Greene

Dietician: Mary Lydon

Men in Friends units tended to represent the greatest diversity with respect to religious identification. Few men in AFSC camps and units reported Friends denominational affiliation when entering CPS and it was not uncommon for the group to include men from a variety of religious groups, in addition to COs reporting no religious affiliation.

In Friends projects, men on average brought 14.27 years of educational experience, with forty percent having completed both college and at least some post graduate education. Forty-three percent of men in Friends camps and units entered with technical and professional work experience, as opposed to eighteen percent among men at Brethren and twelve percent in Mennonite projects. Men in the Friends projects tended to report more urban than rural experience. (Sibley and Jacob pp. 170-172)

The men fought fires, repaired trails, maintained roads and performed other duties.

Adorned in spruce green trousers, T-shirts, sack coats, and caps, the men at CPS 108 at Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee worked nine –hour days six days a week, repairing roads, fixing telephone lines, planting nurseries, clearing trails, managing fire strikes, and eradicating white pine blister rust, a destructive disease that is lethal if allowed to spread from branch to trunk. (Grange p. 3)

“Some COs rose before their 6:15 am wake-up call to attend matins (early morning prayer service), practiced an evening prayer service of vespers, and held a church service on Sunday.” (Grange pp. 3-4)

Some locals called the COs cowards or “yellow bellies” and occasionally roughed them up. Camp Director John Ferguson expressed no doubts about their work, writing to the AFSC about their contribution.

There is a big satisfaction in watching the men respond to the opportunity to help. Considering that none of the CCC units stationed in this area are left and that the present ranger and warden staff are only half as large as they should be, it can be seen that the camp is indispensable to the maintenance of the park.

COs also managed oil and gas records. (Grange p. 4)

CPS program leaders encouraged development of special schools at camps, and persuaded Selective Service on the merits of allowing men to transfer into those camps based on their interests. Gatlinburg developed a School of Race Relations, which permitted men to take courses and participate in activities and events pertinent for those working and living in the South.

For the most part, CPS operated as an interracial community accepting men without concern for ethnicity or national origin. The program assumed operation without discrimination in any aspect of camp work and life. That said, camps operating below the Mason-Dixon Line faced conflicts between CPS views on interracial association and local norms coupled with written or “unwritten” laws.

A crisis occurred at Gatlinburg when an African-American professor from Fisk University classified as IV-E deliberately requested assignment to the camp, knowing the existence of the “unwritten law” banning blacks in the county overnight. The camp vigorously debated its response, with a strong majority taking the position that the camp should be closed if the man was denied acceptance while some of the men, for a variety of reasons, felt he should be assigned to a camp above the Mason-Dixon Line. The Friends C.P.S. Committee took up the issue, and decided to assign him to Gatlinburg without making any note of his race. Selective Service refused, finally sending him to Big Flats.

The results led to the Friends C.P.S. Committee debating the introduction of a policy that all camps would be operated on the basis of racial equality and where the standard could not be met, the camp or unit withdrawn. While the matter was studied, no action was taken, with the end result that the Friends did not consider opening any unit which could not be interracial.

A few men at Gatlinburg volunteered as guinea pigs for research on respiratory diseases. (See CPS 115.33)

Hugh Bustin commented on his time at Gatlinburg. “It was a brotherhood. I learned more as a 19-year-old at the CPS camp than if I’d been at college. I discovered you don’t have to share the same faith to be friends.” (Grange p. 6)

The men published a paper called Calumet from July 1943 through March 1945. George Hogle wrote in an issue Calumet, “The CPS has been a great experience. It opened up new vistas of religion which were unexplored territory for me . . . and I realize only too well the importance of having spiritual companionship and an environment where the world cannot press in so hard on all sides.” (in Grange p. 5)

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

See also Sarah Lewis Armstrong, "The Good War: Life in Civilian Public Service Camp #108." University of North Carolina at Asheville. April 2012.

Kevin Grange, “In Good Conscience”, National Parks 85 (Winter 2011): 26-32.

Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.