CPS Unit Number 046-01

Camp: 46

Unit ID: 1

Operating agency: AFSC

Opened: 8 1942

Closed: 10 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 824

-

CPS Camp No. 46, Big Flats, New YorkProject lunch (outside) at Painted Post Nursery, March 1944Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PennsylvaniaMarch, 1944

CPS Camp No. 46, Big Flats, New YorkProject lunch (outside) at Painted Post Nursery, March 1944Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PennsylvaniaMarch, 1944 -

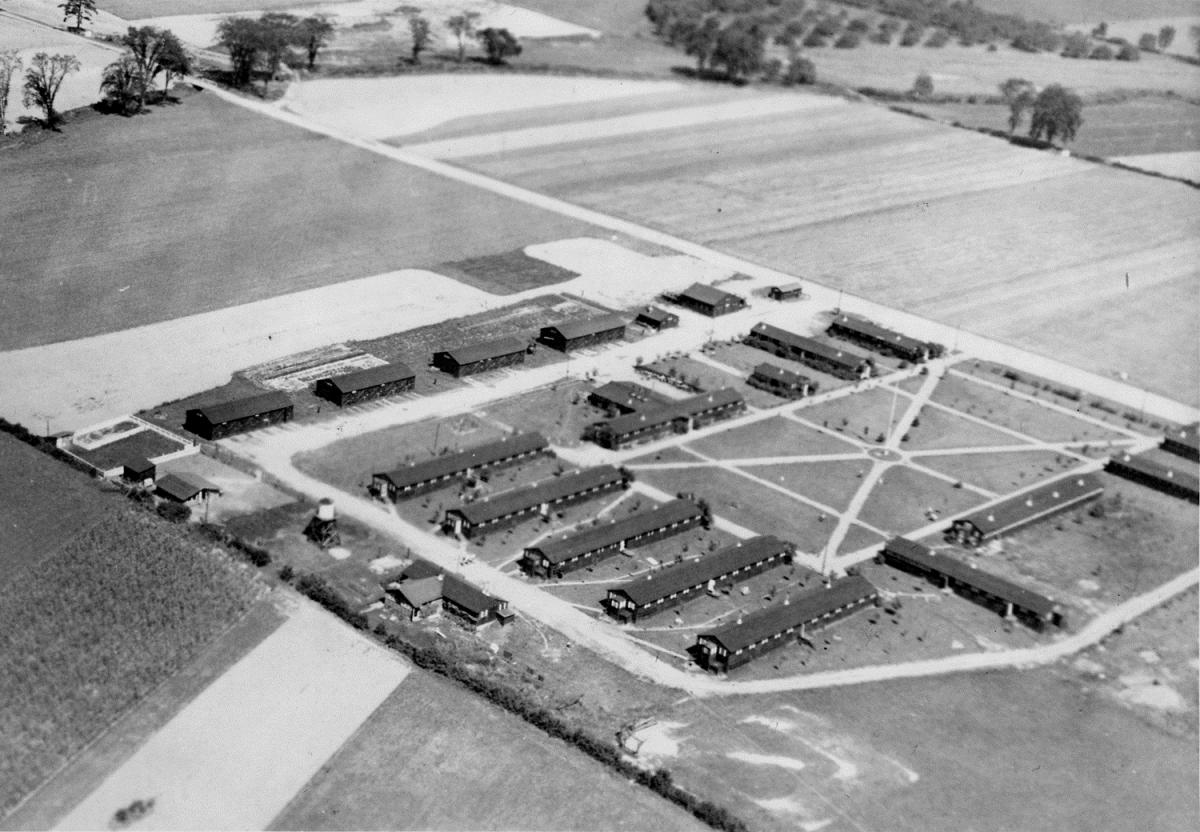

CPS Camp No. 46Aerial photograph of camp locale, Big Flats, New York. 1944.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 46Aerial photograph of camp locale, Big Flats, New York. 1944.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

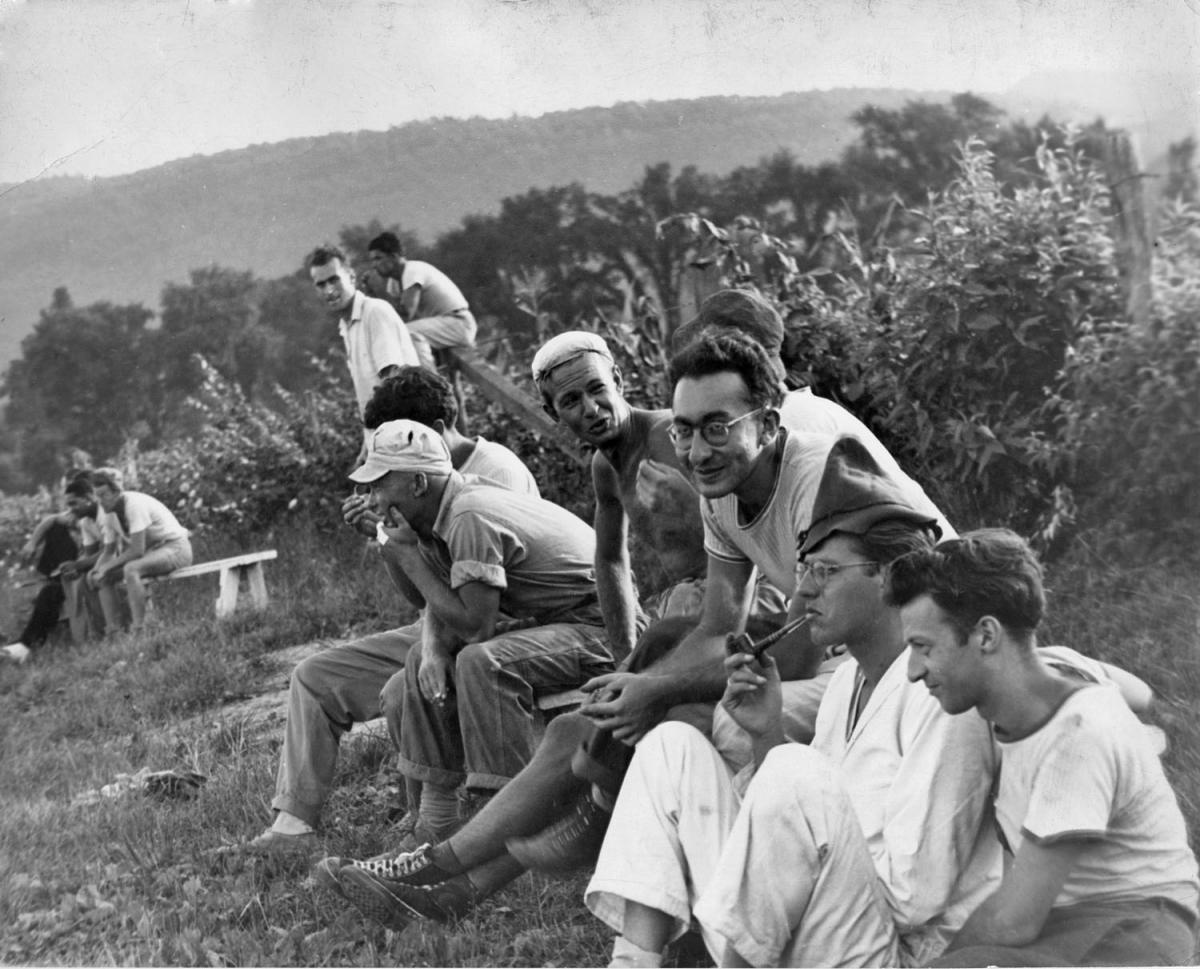

CPS Camp No. 46Group of men watching a ball game. Big Flats, New York. Man in center of photo with glasses is Max Kampelman; he later became chief arms control negotiator for President Reagan.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 46Group of men watching a ball game. Big Flats, New York. Man in center of photo with glasses is Max Kampelman; he later became chief arms control negotiator for President Reagan.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 46Soil conservation – seedlings against erosion. Big Flats, New York. A major project at Big Flats Camp, N.Y., is the preparation of grass seeds and tree seedlings which are distributed along the eastern seaboard by U.S. Forest Service to prevent soil erosion. Here CPS men are harvesting grass from which seeds will be extracted.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 46Soil conservation – seedlings against erosion. Big Flats, New York. A major project at Big Flats Camp, N.Y., is the preparation of grass seeds and tree seedlings which are distributed along the eastern seaboard by U.S. Forest Service to prevent soil erosion. Here CPS men are harvesting grass from which seeds will be extracted.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 46, a Soil Conservation Service base camp at Big Flats, New York operated by the American Friends Service Committee, opened in August 1942. When the American Friends Service Committee withdrew from CPS in March 1946, the Selective Service operated the camp until it closed in October 1946. The men worked to control soil erosion.

The camp was located in a former Civilian Conservation Corps camp near the village of Big Flats, New York in the Chemung River Valley along Route 17. Chemung County bordered Pennsylvania. The area supported agriculture, including tobacco.

Directors: Stephen Cary, Roger Davison, John Hollister, Win Osborne, Tom Potts, Clarence Angell

Men in Friends units tended to represent the greatest diversity with respect to religious identification. Few men in AFSC camps and units reported Friends denominational affiliation and it was not uncommon for the group to include men who reported affiliation with a variety of religious groups, as well as COs reporting no religious affiliation.

In Friends projects, men on average brought 14.27 years of educational experience, with forty percent having completed both college and post graduate education. Forty-three percent of men in Friends camps and units entered CPS from technical and professional work experience, as opposed to eighteen percent among men at Brethren and twelve percent in Mennonite projects. Men in the Friends projects tended to report more urban than rural experience. (Sibley and Jacob pp. 170-172)

A number of the men were married, their wives living in neighboring communities, including Elmira, New York.

Since many campers had dependents and were strapped for cash, at Big Flats, they worked afternoons for the Empire Foods Company in Elmira, in custodial jobs at St. Joseph’s Hospital, or unloading freight cars for the Delaware, Lackawana and Western Railroad.

Men performed hard, menial and often tedious work in soil erosion control. They dug postholes, built fences around pasture land, dug diversion ditches, and grubbed out weeds, as examples.

Men weeded rows of experimental grasses and trees in a 250-acre nursery at Big Flats and at a smaller nursery at nearby Painted Post. After the spring thaw, they uprooted the saplings and packaged them for shipment to thirteen northeastern states where they were planted to reduce soil erosion.

During the winter at Big Flats, men cultivated the forests and cleared fire hazards on state land. In addition, “they constructed two small bridges, built a seed drying shed, renovated an old farmhouse that was used as a nursery manager’s home, and built a dike that prevented heavy property damage to farms west of Big Flats during the floods of January 1943”. After a heavy snow in 1945, crews shoveled out blocked roads. They planted and harvested vegetables on neighboring farms and pruned fruit trees. (Robinson p. 185)

Some COs performed emergency farm labor on dairy farms as many young farmers were away at war.

The American Friends Service Committee designated Big Flats as a “reception center” for new assignees from east of the Mississippi, after it became clear that entering men were often somewhat confused and disoriented about expectations and the nature of the base camp experience. New draftees spent three months with forty seasoned men in an orientation course to CPS. They heard speakers on each of the main CPS projects, and the philosophy and role of each of the administrating agencies. A personnel director interviewed each man on arrival, remained in contact during orientation and conferred with him at the conclusion to help determine an appropriate assignment. Colonel Lewis Kosch, Selective Service Director of Camp Operations, usually presented information on Selective Service policies as well.

In the early years of the program, the religious committees encouraged camp programs devoted to international issues as well as to the challenges of living pacifism. AFSC sponsored an Institute of International Relations at Big Flats. Norman Thomas discussed the future of Germany and a former German government official along with other speakers presented on the topic. Nearly two hundred people, both campers and visitors attended sessions focusing on the question, “Must there Be a Third World War?”

Big Flats organized a School of Non-Violence which lasted two to three months. Organized around week-long visits, leaders such as A. J. Muste, Douglas Steere and Richard Gregg spent time with the men.

The camp director encouraged visitors to the camp as they helped boost morale—wives, girlfriends, students from Cornell and Wells College. At one point, the American Legion Post in Corning objected to Congressman Sterling W. Cole that the camps had “practically no Government supervision”. The Elmira Heights legion post chimed in objecting to men who refused to serve their country as wasting time in insignificant work, “consuming food necessary to severely rationed war workers and others engaged in the war effort. . .while American boys were upholding this democracy on the field of battle”. (Robinson, p. 193) Cole toured the camp, and at the conclusion objected to the visits of wives and girlfriends, protocols for which were addressed in Selective Service policy. This resulted in an investigation by Lt. Colonel Franklin McLean, a field inspector for Colonel Kosch’s Camp Operations Division in Selective Service. Following his visit, he was able to convince Cole that all was in order.

Men at Big Flats, when required to perform emergency farm labor on dairy farms without pay, joined other COs in objecting to the practice of farmers paying Selective Service for their labor. Their concern was that the money was theirs and should not be used to support war efforts. Representative Sterling W. Cole, a Republican, at first incensed at COs, was reported to have visited with the men at Big Flats; however, he came to understand that they were not slackers but were sincerely concerned that their earnings would be directed to war efforts.

As a result, after many efforts to secure Congressional action on behalf of COs who had objected to not being paid when they were assigned to work for farmers and other private employers, Representative Cole consulted with the National Service Board of Religious Objectors (NSBRO) and Selective Service before introducing a bill to turn over the CO earnings held in a “frozen fund” to the Office of Foreign Relief. However, each attempt was ultimately blocked by influential persons in the Military Affairs Committees, the House and the Senate, or maneuvers by Selective Service. The fund was never released to be directed to CPS causes and interests.

Men at Big Flats objected to the nature of other assignments as well. Richard Sterne wrote to the Providence Friends Meeting in Wallingford, Pennsylvania on May 22, 1943 about work duties as “senseless, routine, without goal. It deadens initiative and makes no use of talent. One comes to feel that every moment spent on work on the project is waste.”

Stephan Cary wrote to AFSC on July 29, 1942. “How can we be content day after day to manicure mountains when the world has such crying need for practical real help and help that we want to give”? (reported in Sibley and Jacob p. 259).

Soil Conservation Service supervisors did not help the situation, apparently lacking understanding of the COs, and also supervisory skills. That coupled with a general discontent with the nature of the work created difficulty early on.

On the second anniversary of the Selective Service Act, October 16, 1942, Stanley Murphy and Louis Taylor walked out of Big Flats as they did not believe they could continue to do work that seemed insignificant to them. Both were highly respected by camp men and leaders. On February 12, 1943, they began serving a two and a half year sentence in Danbury Federal Correctional Institution and began a “fast unto death” against the conscription system. After an eighty-two-day fast, they were offered parole to charitable institutions. However, confusion over the terms and conditions of the parole resulted in their transfer to the Prison Medical Center in Springfield, Missouri, a prison for “psychoneurotics, psychotics and other unusual cases”. During their time at Springfield, they exposed conditions of mistreatment of inmates that resulted in several investigations. (See Sibley and Jacob pp. 412-416)

In a protest of conscience, as increasing numbers of COs objected to infringement of freedoms as well as well as military implications of the program, David Metcalf walked out of camp in repudiation of CPS as he believed it was not a true alternative to military service.

In May, 1946, more than half a year after the war’s end, thirty-five men stopped work in an attempt to force action on accumulated grievances of CPS men. At the same time seventy men at Glendora in California took the same action. This occurred after the Selective Service had taken over administration of the camp. The grievances included “arbitrary transfer of assignees, the imposition of unjust penalties, the lack of dependency allotments, slow demobilization, forced labor without pay”, and even the system of conscription in general. (Sibley and Jacob p. 272)

With all the pressures of camp life and work, several men found the time to volunteer in the community as hospital orderlies. Others played in a city baseball league while forty-two men assisted in the renovation of a local youth recreation center. Musicians in a camp orchestra, a Glee Club, and the “Four Big Flats” quartet performed throughout the area for churches, the Grange and Elmira YMCA. (Robinson p. 193)

The men published a camp paper Weekly Safety Bulletin during 1943-44. Additional camp publications included Big Flats Bulletin, published from May 1945 through October 1945; Big Flats Newsletter/News and Views, published from February 1943 through March 1944; Grass Roots, with five issues published from September 1942 through March 1943, and Vol. 2 No. 1 published in August 1943; Tree Haven Times, with Vol. 2, no. 1 (August 1943) listed in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection Camp publications.

For stories from men who, as COs, walked to a different drummer during World War II, see Mary R. Hopkins, Editor, Men of Peace: World War II Conscientious Objectors. Caye Caulker, Belize: Producciones de le Hamaca, 2010, Samuel P. Hays pp. 193-202; Charles R. Lord pp. 149-158; Harlan Smith pp. 162-173.

For general information on CPS camps see Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. Intercourse, PA: Good Books 1990.

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

For information on protests over the use of funds resulting from CPS labor, see Steven M. Nolt, “The CPS Frozen Fund: The Beginning of Peace-time Interaction Between Historic Peace Churches and the United States Government.” Mennonite Quarterly Review, 67 (April 1993), 201-224.

For additional information on the Big Flats camp, see Mitchell Robinson, “Men of Peace in a World at War: Civilian Public Service in New York State, 1941-1946”, New York History 78:2 (April 1997): 174-210.

For additional information on protests of conscience, see Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952 pp. 257-279.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.