CPS Unit Number 003-01

Camp: 3

Unit ID: 1

Title: Patapsco

Operating agency: AFSC

Opened: 5 1941

Closed: 9 1942

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 154

-

CPS Camp No. 3, Group PhotoCPS Camp No. 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, Maryland. Group Photo.Digital image from Civilian Public Service Records (DG056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania.

CPS Camp No. 3, Group PhotoCPS Camp No. 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, Maryland. Group Photo.Digital image from Civilian Public Service Records (DG056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania. -

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandMen playing softball/baseballDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandMen playing softball/baseballDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942 -

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandOlder man & CPSer talkingDigital Image from Paul wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandOlder man & CPSer talkingDigital Image from Paul wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942 -

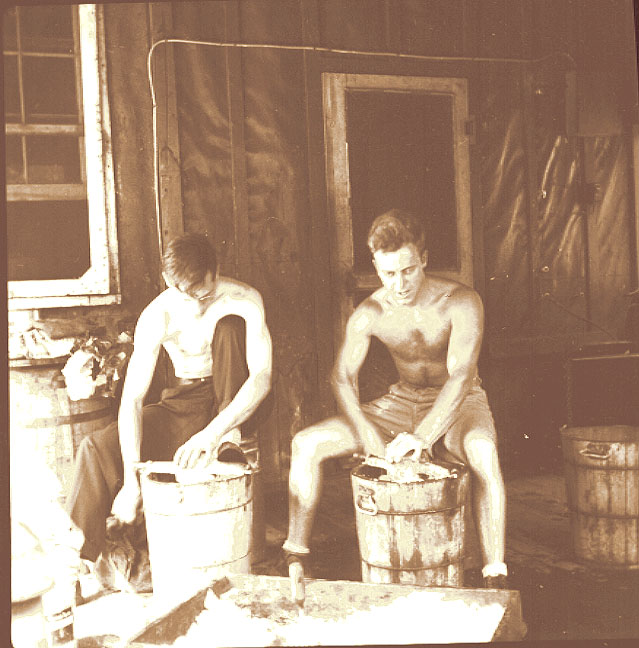

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandTwo men churning ice creamDigital Image from Paul wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandTwo men churning ice creamDigital Image from Paul wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942 -

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSers shelling peasDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSers shelling peasDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942 -

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSers trying out newly (?) constructed privy for a laugh.Digital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSers trying out newly (?) constructed privy for a laugh.Digital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942 -

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSer & older man outdoorsDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSer & older man outdoorsDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942 -

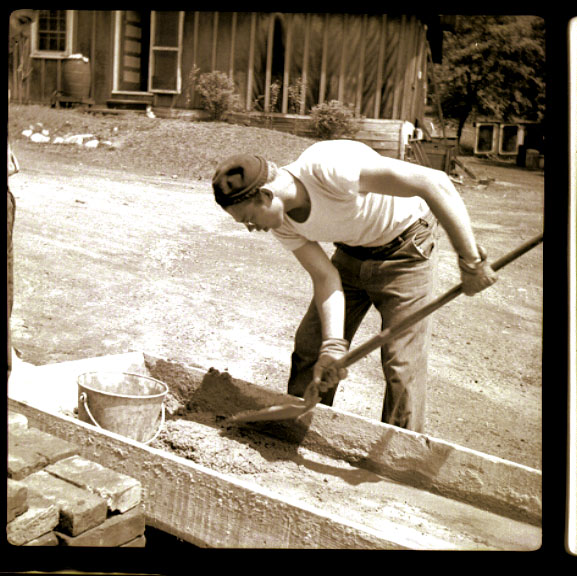

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSer mixing cementDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSer mixing cementDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942 -

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandBulldozer at partially cleared siteDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandBulldozer at partially cleared siteDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942 -

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSers inside and outside of trucksDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSers inside and outside of trucksDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942 -

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSer & woman with puppy, outside cabin,Digital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSer & woman with puppy, outside cabin,Digital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942 -

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSers singing around the pianoDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandCPSers singing around the pianoDigital Image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942 -

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandTwo CPSers digging ditch in woods to lay water pipeDigital image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers (CDGA), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

CPS Camp # 3, Patapsco, Elkridge, MarylandTwo CPSers digging ditch in woods to lay water pipeDigital image from Paul Wilhelm Collected Papers (CDGA), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1942

-

-

1942

1942 -

1942

1942 -

1942

1942 -

1942

1942 -

1942

1942 -

1942

1942 -

1942

1942 -

1942

1942 -

1942

1942 -

1942

1942 -

1942

1942 -

1942

1942

CPS Camp No. 3, a National Park Service base camp located in an abandoned CCC camp in the Patapsco State Forest near Baltimore, and operated by the American Friends Service Committee, opened in May 1941 and closed in September 1942. Men in the National Park Service camps fought fires and performed park maintenance.

This National Park Service base camp was located in an abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camp in the Patapsco State Forest. . .”wedged precariously between the main freight line of the B & O [railroad] on the north and the gently flowing Patapsco River on the south, approximately eleven miles from Baltimore. . ..” (Freeman, p. 1) Operated by the American Friends Service Committee, the camp opened on May 15, 1941 and closed in September 1942.

Directors: Gordon Foster, Russell Freeman, Arthur Gamble, William Mackensen, Ernest Wildman, Dan Wilson

Dietician: Nancy Foster

“The first twenty-six conscientious objectors arrived with fifty-four reporters and photographers in tow.” (Keim p. 39) This first CPS camp was often called “the gold fish bowl”. Reporters first focused on the peculiarity of CO beliefs.

Unlike many Friends camps, the population at Patapsco was relatively homogeneous. Approximately one-third reported their denominational affiliation when entering CPS as Friend, another third reported affiliation with mainstream Protestant denominations, and the final third listed other Protestant denominations (Chistadelphians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, etc.) or non-affiliate. Typical of Friends camps, most men entered CPS from urban backgrounds.

As one of the camp directors noted,

Patapsco had color and variety. Tony Carnevale, a second generation Italian firebrand who had joined the Jehovah’s Witness sect, tap-danced, scrapped, and quoted scripture with torrential velocity in those early days . . .. John “meat” Yanger was an Allentown, Pennsylvania, ex boxer and wrestler who retired from the big time because he “didn’t want to hurt nobody, and besides it ain’t Christian.” . . .”Doctor” Fran Marburg, was long on “theoretically speaking,” incurably inquisitive about words like “God,” “Christian,” and “sacrifice,” while being constantly concerned and ready to act upon matters of common interest. Arle Brooks, tall Texan parolee from Danbury, possessed a great gift for friendship and gave the camp a strong, Thoreau-like religious leader. (Freeman p. 9)

Relatively well educated, more than half had some college education or beyond and many were oriented toward the professions or preparing for them. Only twenty-five percent had worked in technical, skilled or unskilled jobs. (Sibley and Jacob p. 172)

Men in the National Park Service camps fought fires and performed park maintenance. At Patapsco they reconditioned the camp, built picnic tables and cleared forest among other maintenance and fire fighting duties.

Nancy Foster, a Swarthmore College educated school teacher from Ohio was able to negotiate a release from her school contract to join CPS as a dietician. Enduring delays and difficulties in opening the Patapsco camp and furnishing the kitchen, she persevered and helped colleagues open the camp. Over the next few years she worked as dietician in five camps, and became keenly aware of the problems of trying to maintain harmony in them. (Goossen pp. 84-85)

Since the camp was only eleven miles from Baltimore and was served by a regular suburban bus, the men in the camp did not experience the isolation common in many other camps. “During the early months . . . we engaged in considerable visitation, mostly to nearby church groups. Baltimore proved to have a warm heart and we were generously entertained and visited by Friends and non-Friends, pacifists and others during the entire period of stay.” (Freeman p. 9)

The men established a camp government almost immediately. Initially, camp meetings were held weekly and decisions were made based on “the sense of the meeting”. As the population grew and became more diverse, consensus decision-making became unworkable and camp decisions were made by two-thirds majority vote. A Steering Committee established initially to review issues and channel them to the camp meeting, eventually became more of an executive committee making many decisions itself.

“The stable elements of Patapsco life were much the same as those in all CPS camps . . . project work, meditation for a small group, crowded evening hours for classes, meetings, letters, sports and relaxation.” (Freeman p. 9)

Then the men in the camp learned of a plan to have them build a road to a new air raid tower, they protested vigorously that they should not be asked to work on any project of possible military significance. An appeal to General Hershey resulted in an important policy clarification upholding the camp’s position.

Corbett Bishop, one of the COs, owned a bookstore prior to his induction. After serving three months he asked for a furlough because his business was heading into foreclosure. He had insufficient time from notice of induction to reporting to wind up his affairs. After no response to his appeal for a furlough, he began fasting to protest, not only non response to his furlough request, but also the system of forcing CPS men to work without pay. His protest continued for two months, including hospitalization prior to his being transferred to West Campton, New Hampshire CPS Camp No. 32. He became a leader among “absolutists” in CPS who believed that at some point, law or regulation needed to be breached as a matter of principle on issues of conscience. (Sibley and Jacob pp. 401-410; see also "Bishop Ends 44 Days" under "Other Materials")

As the camp size increased and the war began, the men began to deal with the realities of work without pay on “uncongenial projects”, financial worries, diminished sympathies toward conscientious objectors, and individual rights within a rapidly changing group of men, generally with limited skills in group techniques.

The men published a camp paper The Patapsco Peacemaker, beginning in July, 1941 and continuing through December 1942.

A first-hand account of CPS #3 by Russell Freeman, “In the Beginning: The Story of the First C.P.S. Camp” appeared in the CPS magazine The Compass, Vol. 1 No. 3 (Spring 1943): 8 ff.

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

See Kevin Grange, “In Good Conscience”, National Parks (Winter 2011) http://www.ncpa.org/magazine/2011/winter/in-good-conscience.html?

For stories from men who, as COs, walked to a different drummer during World War II, see Mary R. Hopkins, Editor, Men of Peace: World War II Conscientious Objectors. Caye Caulker, Belize: Producciones de le Hamaca, 2010, Roger D. Way, pp. 212-216.

For more information on Work of National Importance including National Park Service Camps see Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. Intercourse, PA: Good Books 1990, 39-57.

For more information on CPS #3 at Patapsco State Park see Edward Orser, “Involuntary Community: Conscientious Objectors at Patapsco State Park During World War II,” Maryland Historical Magazine 72 (1), (Spring 1977): 132-146.

For more information on absolutists in CPS see Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-1947. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952, 401-418.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.