CPS Unit Number 090-01

Camp: 90

Unit ID: 1

Title: Ypsilanti State Hospital

Operating agency: MCC

Opened: 3 1943

Closed: 10 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 137

-

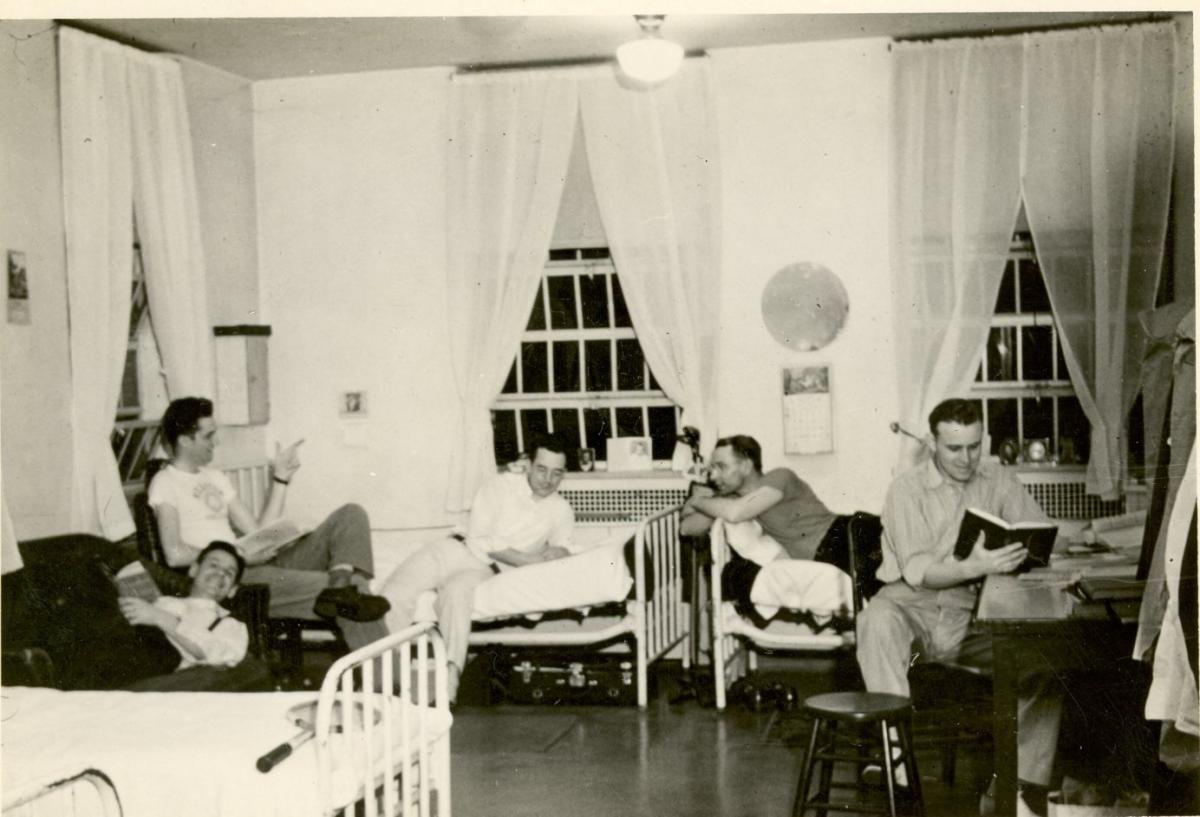

CPS Camp No. 90, Ypsilanti, MichiganCivilian Public Service, camp 90, Ypsilanti, Michigan. Bull-session in dormitory in the single men's quarters on A 2-1. Left to right: Daniel Diener, Ralph Buckwalter, Lloyd Conrad, Lawrence Hilty, Lawrence Greaser.Photo 267a Box 2, Folder 13. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 90, Ypsilanti, MichiganCivilian Public Service, camp 90, Ypsilanti, Michigan. Bull-session in dormitory in the single men's quarters on A 2-1. Left to right: Daniel Diener, Ralph Buckwalter, Lloyd Conrad, Lawrence Hilty, Lawrence Greaser.Photo 267a Box 2, Folder 13. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 90Civilian Public Service, camp 90, Ypsilanti, Michigan. Vincent Kraybill, Mrs. Waldo Janzen, Roman Slabaugh.Box 2, Folder 13. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 90Civilian Public Service, camp 90, Ypsilanti, Michigan. Vincent Kraybill, Mrs. Waldo Janzen, Roman Slabaugh.Box 2, Folder 13. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

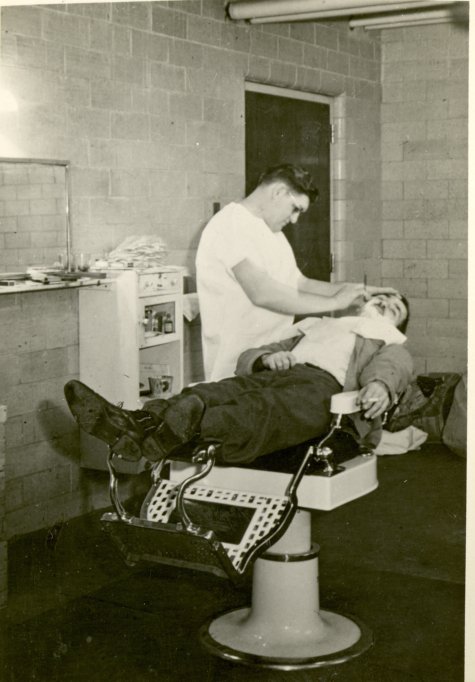

CPS Camp No. 90Civilian Public Service, camp 90, Ypsilanti, Michigan. Ralph Pletcher shaving patient.Box 2, Folder 13. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 90Civilian Public Service, camp 90, Ypsilanti, Michigan. Ralph Pletcher shaving patient.Box 2, Folder 13. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 90Civilian Public Service, camp 90, Ypsilanti, Michigan. A group picture showing most of the girls in the unit.Box 2, Folder 13. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 90Civilian Public Service, camp 90, Ypsilanti, Michigan. A group picture showing most of the girls in the unit.Box 2, Folder 13. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Unit No. 90, a Mental Hospital unit at Ypsilanti State Hospital near Ypsilanti, Michigan operated by Mennonite Central Committee, opened in March 1943 and closed in October 1946. The majority of the men served as ward attendants.

Ypsilanti State Hospital, with a capacity of thirty-three hundred patients, was located eight miles south and west of Ypsilanti and ten miles south of Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Built in 1931 and located on twelve hundred acres, the hospital provided well equipped kitchens, cafeterias, bakery, laundry, warehouses, dairy, orchards, and farm land. The recreational facilities included men’s and women’s gymnasiums, athletic, music and motion picture equipment, golf courses, and tennis and shuffleboard courts.

Patients, supervised by members of the unit, performed much work at the hospital. “Many worked in the occupational therapy department weaving, sewing, repairing furniture, and engaging in a variety of other manual arts.” (from the Mennonite Central Committee News Letter, June 22, 1943, p. 1, 2 in Gingerich p. 234)

Directors: Lotus Troyer, Lloyd Conrad, John Fisher, John Juhnke

Summer Service Leader: Lois Gunden

Fifty men were selected from Mennonite Central Committee base camps at Fort Collins, Colorado CPS No. 33, Downey, Idaho CPS No. 67, Hill City, South Dakota CPS No. 57, and Belton, Montana CPS No. 55. Another twenty-five men arrived later.

Typically in Mennonite camps and units, the majority reported affiliation with a variety of Mennonite and Amish groups when entering CPS. On average, men had completed 10.45 years of education, with nearly twenty-two percent having attended some college or graduated, and some completing graduate and postgraduate work. Fifty-nine percent reported occupations on entry into CPS as farming or other agricultural work while twelve percent reported technical or professional work. (Sibley and Jacob pp. 171-72)

According to Gingerich, an average of thirty-five wives and friends of the assignees worked at the hospital as well. Goossen reports that more than one hundred women joined the CPS community as employees, volunteers and participants in foreign relief training. (p. 58)

In 1944 and 1945, two summer service units of thirty-six women and fifteen women respectively, worked at the hospital. Lois Gunden of Goshen College led the units. In August 1943, a CO girls group formed at Goshen College. Known as “COGs”, the women expressed their convictions on peace and war, and sought to support the stands taken by young men. The women committed to relieve human need, sought locations and opportunities to act on their commitments.

The unit size reached seventy-five men. An average of fifty men worked as ward attendants; fourteen worked in the three kitchens preparing patient food; the remaining assignees filled roles as electrician, occupational therapist, farm helper, warehouse attendant, grocer, laundryman, barber, recreational therapist and hospital driver.

The length of the work week varied according to role, with ward attendants working a fifty-four hour work week with the sixth day off. Kitchen personnel worked forty-eight hour weeks, and those in office roles worked a forty hour work week.

John J. Fisher, Jr. wrote about his experiences at the hospital.

Here the assignment on the wards gave me at first hand a real sense of daily constructive service. Here I gained another kind of invaluable education, from bed pans and epileptic seizures to the dilemmas of a short-staffed state institution.

There was also an inevitable tension with state employees, many of whom had little knowledge of our legal status or agreed with our conscientious scruples about the patients in our care. At one time there appeared The Buttercup News which savagely ridiculed us as “yellow bellies” and self-righteous interlopers on patriot turf.

At the same time, however, a number of “staties” became our friendly co-workers under often demanding circumstances. (“Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories p. 15)

Single men lived in comfortable living quarters in a former patient ward. Married couples lived in the employees’ building.

Selective Service Directive # 3 specified compensation and benefits for those working in hospital units. Assignees were to receive food, living quarters, laundry service, uniforms or work clothes, or a cash equivalent not to exceed five dollars, a maintenance allowance of ten dollars per month, the same medical and dental attention offered to regular employees, transportation by the most direct route possible to and from camp, and worker’s compensation insurance provided by state law. At Ypsilanti the men received no salary, but rather a maintenance allowance of fifty dollars per month from which was deducted thirty-five dollars for food, living quarters and laundry.

Hospital superintendent Dr. O. R. Yoder, a former Mennonite and graduate of Goshen College, was both supportive of the CPS unit and also was recognized as running a progressive hospital. He regularly made himself available to both unit leadership and members. He also expressed gratitude that the unit “came quietly into the hospital and accepted their assigned duties”, even though the unit was frowned upon by labor organizations and veterans groups.

The men formed unit committees (athletic, music, library, shop, religious life) to plan activities. A Unit Council with representatives of each of the committees and staff not only brought matters to the men for discussion and action, but also held men in the unit accountable.

Lawrence Greaser, who served as an attendant on the violent ward during his service at Ypsilanti, “sang in quartets in all of the units and while at Ypsilanti our quartet traveled many weekends with Lotus Troyer, our camp director. We visited Mennonite, Brethren and Friends congregations in Indiana, Michigan and Ohio.” (“Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories p. 19)

In mental health hospital units, the CPS unit director served as an assistant director reporting to the hospital superintendent. Assistant directors, in addition to being in direct charge of unit personnel, prepared reports for MCC, the National Service Board of Religious Objectors (NSBRO) and the Selective Service.

The educational program focused on relief training. A group of twenty-five men took evening courses in preparation for foreign relief, including French, Spanish, mental hygiene, international relations and Mennonite relief work, Mennonite history, social work and Bible. Women from the summer service program, as well as those who participated in a year-round program, took courses in foreign relief work as well.

With the larger number of women active in the CPS unit at the hospital, a “C. O. Girls” unit formed. As Congress was debating the Austin-Wadsworth proposal to draft women, men and women in CPS units did as well. At Ypsilanti, Amanda Ediger, a student working as a ward attendant to earn college tuition, wrote to her parents: “You know if they are going to conscript women, they will surely be able to take me. The only thing that could keep me out would be working in a mental hospital. They aren’t making any provisions for C.O.s, either.” (Goossen p. 102-03)

Church officials valued the contributions of summer interns and C. O. Girls, primarily since they contributed greatly to increase in unit morale. Doris Miller, a Goshen student who served at Ypsilanti, noted her motivations as being more complex. “I was challenged to become a part of mental health work because of my own deep convictions. My motivation: to support CPSers and to contribute to peace.” (Goossen p. 104)

Ruby Martin Zook worked at the hospital beginning in January 1944 as part of the CO women’s unit.

My first assignment was to accompany a number of patients to the dentist who was located in another part of the hospital. The patient group was large and I was the lone attendant and our route took us through a closed tunnel. The experience was frightening but all went well. Another first day duty was to hold the legs of patients while they were given electric shock treatment. This too was frightening. (“Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories pp. 104-105)

Lucille Graber Swartzendruber worked during the summers of 1944 and 1945 on the bed wards. “Taller women in the unit were assigned to wards that had more potential for violence.”

Those summers were the first and best opportunity I had as a young woman to identify with the message of non-resistance and commit myself to seek peaceful solutions to conflict. It moved me from theory to practice, to be a part of a peace process which sought negotiation and understanding rather than militant conflict. (“Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories pp. 102-103)

Thelma Miller Groff worked on Ward C.

To give patients my listening ear and to keep believing in the humanity of each was part of the challenge. I remember how good I felt when I was able to affirm Mr. Thompson for his faithful visits to his wife each week. He had not realized that his wife was much quieter in her padded cell after his visits.

Our unit leader, Lois Gunden, arranged for us to attend two summer classes all summer. Both gave meaning to the experience. One class taught by the hospital superintendent dealt with how to better understand mental illness. Lois taught a class for those who were preparing to do relief work after the war.

(“Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories pp. 98-99)

Florence Nafziger worked as a staff nurse on a disturbed women’s ward. “I was fortunate to have a supervisor who was kind and treated patients like people. Even if their behavior was abnormal they were to be treated as normally as possible. . . .One impression that has stayed with me is what was significant and truly profound about the service the Mennonite Church was giving through its young people: Those young people were the Church in that situation.” (“Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories p. 99)

Women participated in many of the activities including the CPS choir, which frequently presented programs for patients.

Men actively participated in softball games with others in the unit and with patients.

With respect to interaction with church communities, since Mennonite communities existed near Ypsilanti, many Mennonite speakers and ministers visited the camp and contributed to the program. The unit held Wednesday evening prayer services, Sunday morning Sunday school, and Sunday evening services. Sunday offerings averaged $30 dollars and were contributed to the MCC War Sufferers relief fund.

Near the end of the unit some employees, presumed to be returning servicemen, circulated “an abusive printed sheet” among employees. The Buttercup News reported on “indiscreet words and behavior” of a few assignees. Later, in their weekly publication, patients in the recreational therapy department defended the CPS men, referring to the writer as “a hothead letting off steam”. (The Weekly Slants, April 23, 1946, pp. 1, 2, 6 in Gingerich p. 235-36)

In a 1988 survey reflecting back on his CPS experience, one man responded:

While working at the Ypsilanti unit, I came to understand that Mennonites could make an impact on society and on institutions. The CPS unit at this hospital was, in itself, a power-block and proved it could be effective in bringing about positive changes in institutional life. . . . We were respected for our work performance and this might have been the beginning of helping me to become less timid and actually start feeling good about being a Mennonite. (in Sareyan p. 249)

The men published Ypsi, much like a yearbook, which contained photos and a history of the unit.

For more information on this unit and other mental health and training school units, see Melvin Gingerich, Service for Peace: A History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service. Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee printed by Herald Press, Scottdale, PA 1949, Chapter XVI, pp. 213-251.

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

For personal stories of CPS men, see Peace Committee and Seniors for Peace Coordinating Committee of the College Mennonite Church of Goshen, Indiana, “Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories. Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1995, 2000.

See also Alex Sareyan, The Turning Point: How Persons of Conscience Brought About Major Change in the Care of America’s Mentally Ill. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1994.

For an in depth history of conscientious objection in the United States, see Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-1947. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.

For more in depth treatment of mental health and training school units, see Steven J. Taylor, Acts of Conscience: World War II, Mental Institutions, and Religious Objectors. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2009.