CPS Unit Number 075-01

Camp: 75

Unit ID: 1

Title: Medical Lake Hospital

Operating agency: AFSC

Opened: 2 1943

Closed: 5 1945

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 36

-

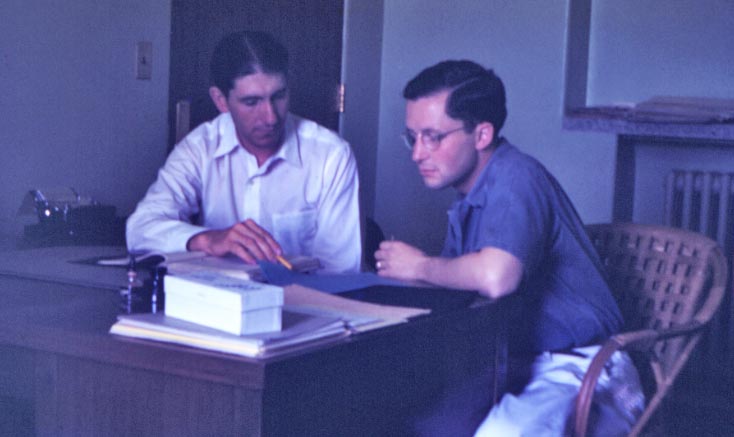

CPS Camp No. 75Medical Lake Hospital StaffDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 75Medical Lake Hospital StaffDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 75Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington.Washington State Archives, Box 9, 02A701

CPS Camp No. 75Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington.Washington State Archives, Box 9, 02A701 -

CPS Camp No. 75Medical Lake Building.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 75Medical Lake Building.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 75Medical Lake Farm.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 75Medical Lake Farm.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Unit No. 75, a Mental Hospital unit located at Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington operated by the American Friends Service Committee, opened in February 1943 and closed in May 1945. The men served in the wards.

Eastern State Hospital was located in Medical Lake, Washington, less than twenty miles southwest of Spokane.

Directors: Joseph Coffin, Clarence Angell, Samuel Stellrecht

When entering CPS, men in Friends camps and units reported the most diversity in religious affiliation, including those who reported no affiliation. When compared with men in other CPS camps and units, the men in AFSC camps reported have completed an 14.27 years of education, a significant number with graduate level education. Forty-three percent reported technical and professional occupational experience at point of entry into CPS. (Sibley and Jacob pp. 171-72)

Several of the men at Medical Lake were married.

The majority of the men worked in the wards covering both day and night shifts. Wives also assisted at the hospital, receiving pay for their work as they were not subject to Selective Service regulations.

In a 1988 survey, one man recalled the extent of hostility toward the unit. “During the second year of our stay at Medical Lake State Hospital, several wives of the CPS men who had been hired to fill staff vacancies were dismissed because they refused to buy war bonds”. (in Sareyan p. 241)

The hospital provided space for a CPS office as one of the doctor’s offices was not in use.

One CO, in a 1988 survey, reflected back on his experience at the hospital and in the community.

At the opening of our unit at the Medical State Hospital in Washington, there was a great deal of opposition, even enmity, directed at our CPS unit by both the hospital staff as well as the community. We were socially rejected, both at the hospital as well as the community. The Methodist minister who was supportive and friendly to us lost his post because of his support for us. . . . By the end of two years the unfriendly climate in which we found ourselves turned to nearly cordial. (Sareyan p. 240)

Another CO, responding to the same survey, recalled his experience.

This was a time of personal growth for me. Before my arrival at the Medical Lake unit, I had had little contact with the real world of pain, illness, deprivation, and emotional turmoil. Within the first month of my arrival at the hospital I was ambushed and beaten by two patients. Through the support of others in our CPS group and sympathetic patients, I lost my fears. By not retaliating against my attackers, I became in, as well as theory, a nonviolent person. (in Sareyan pp. 251-52)

In the same survey another man reflected, “In a real sense, I grew up during my stay as an attendant at Medical Lake. I moved away from being a protester, and instead became an agent for social change”. (Sareyan p. 251)

From November 1943 through June 1944 the men published the Journal of Unitology. In an undated one-page issue from Vol. 1, Phil Gifford, substituting for the regular editor, notified the men of recent materials received, magazines ordered, and reported news on the opening of the School of Fine Arts at Waldport as well as a Big Flats proposal for a representative policy making body for CPS men.

The men appreciated that the hospital was not far from Spokane where they could “get away”.

They published a unit paper called The Ex-Change beginning in February 1944 and continued through March 1945. Ex-Change reported on a series of issues related to unit morale. Vol. I:4 (undated) reported on a visit from Dick Reuters of American Friends Service Committee (AFSC). In it the men shared their feelings of isolation since it appeared that the AFSC leaders were “too far away” and “too busy” to maintain contact with them. Reuters urged the men to make their feelings known to Philadelphia.

The July 8, 1944 issue headlined homework for an upcoming meeting about the wisdom of and motives behind the Friends decision to become involved in CPS. The men were asked to review twelve pages on reserve in the CPS library on how the Friends became involved in CPS, as well as additional reading on the development of pacifism in the western world, and on the mental hygiene program of CPS.

The October 14, 1944 of X-Change reported on a sense of complacency in the unit and that the men needed to be doing more for the patients. The summary outlined an approach to addressing the concern at an upcoming meeting.

Why do we feel we should be doing more?

What do the patients need?

What can we do?

What problems are involved?

It closed with the announcement of two times for unit members to discuss the issue on the following Saturday, with wives invited to join in discussion of bettering the lives of the patients.

The October 19 X-Change opened by framing an issue for debate: “The Friends should have no part in any alternative service program under a peace-time conscription act”. Chuck McEvens, Dale Porter, Bob Morgan and Clarence Angell each summarized their view in advance of two meetings, one for Day Men on Wednesday night and the other on Thursday morning for Night Men.

After a visit by Mr. Weaver of the National Service Board for Religious Objectors (NSBRO), the December 4, 1944 X-Change summarized issues regarding the future of the unit. Superintendent Perry had hired a few more regular employees, and the men, AFSC and NSBRO . . . “all agreed that our maintenance based labor would not displace nor compete with people for wages”. Since the unit was created to address acute staff shortage, then the unit “should be withdrawn when a supply of labor reappeared”. Dr. Perry desired an orderly reduction and transition plan that would reduce the unit to fifteen. The March 6, 1945 issue reported that seven men were transferring out and the unit would be reduced further to ten. The unit closed two months later.

The men published one issue of High Time in July 1945. The Swarthmore College Peace Collection holds the 25th issue of House Organ published July 17, 1945.

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

The Exchange (also X-Change) Vol. I No. 4 undated; unnumbered (July 8, 1944); unnumbered (July 9, 1944); unnumbered (October 14, 1944); unnumbered (October 19, 1944); unnumbered (December 4, 1944); unnumbered (March 6, 1945) in Swarthmore College Peace Collection, American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Section 3, Box 14.

Journal of Unitology Vol. 1 unnumbered (June 16, 1944) in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Section 3, Box 14.

See also Alex Sareyan, The Turning Point: How Persons of Conscience Brought About Major Change in the Care of America’s Mentally Ill. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1994.

For an in depth history of conscientious objection in the United States, see Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-1947. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.

For a more in depth treatment of the mental health and training units, see Steven J. Taylor, Acts of Conscience: World War II, Mental Institutions, and Religious Objectors. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2009.