CPS Unit Number 063-01

Camp: 63

Unit ID: 1

Title: New Jersey State Hospital

Operating agency: MCC

Opened: 11 1942

Closed: 10 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 179

-

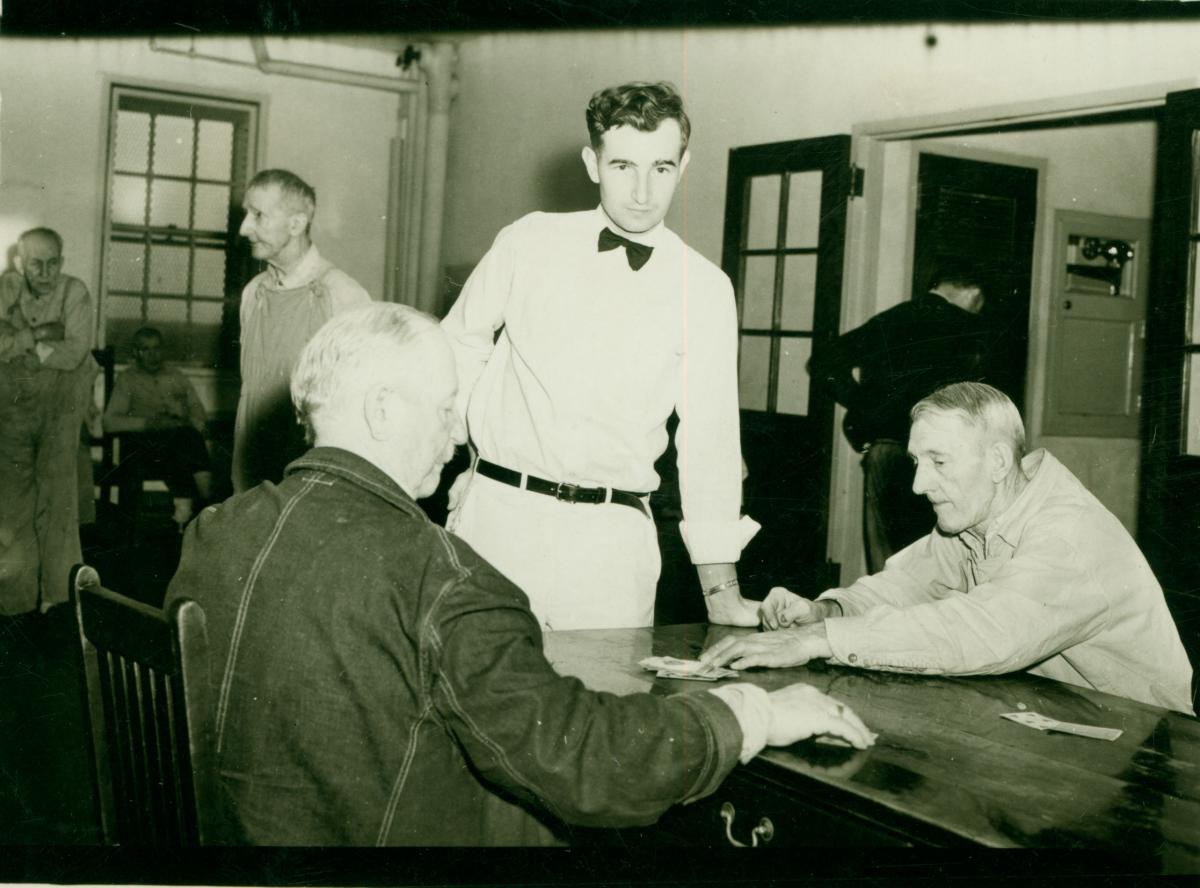

CPS Camp # 63, New Jersey State Hospital, Marlboro, New JerseyAfternoon relaxation, Harold Martin looking in during card game.Digital Image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansasca. 1945

CPS Camp # 63, New Jersey State Hospital, Marlboro, New JerseyAfternoon relaxation, Harold Martin looking in during card game.Digital Image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansasca. 1945 -

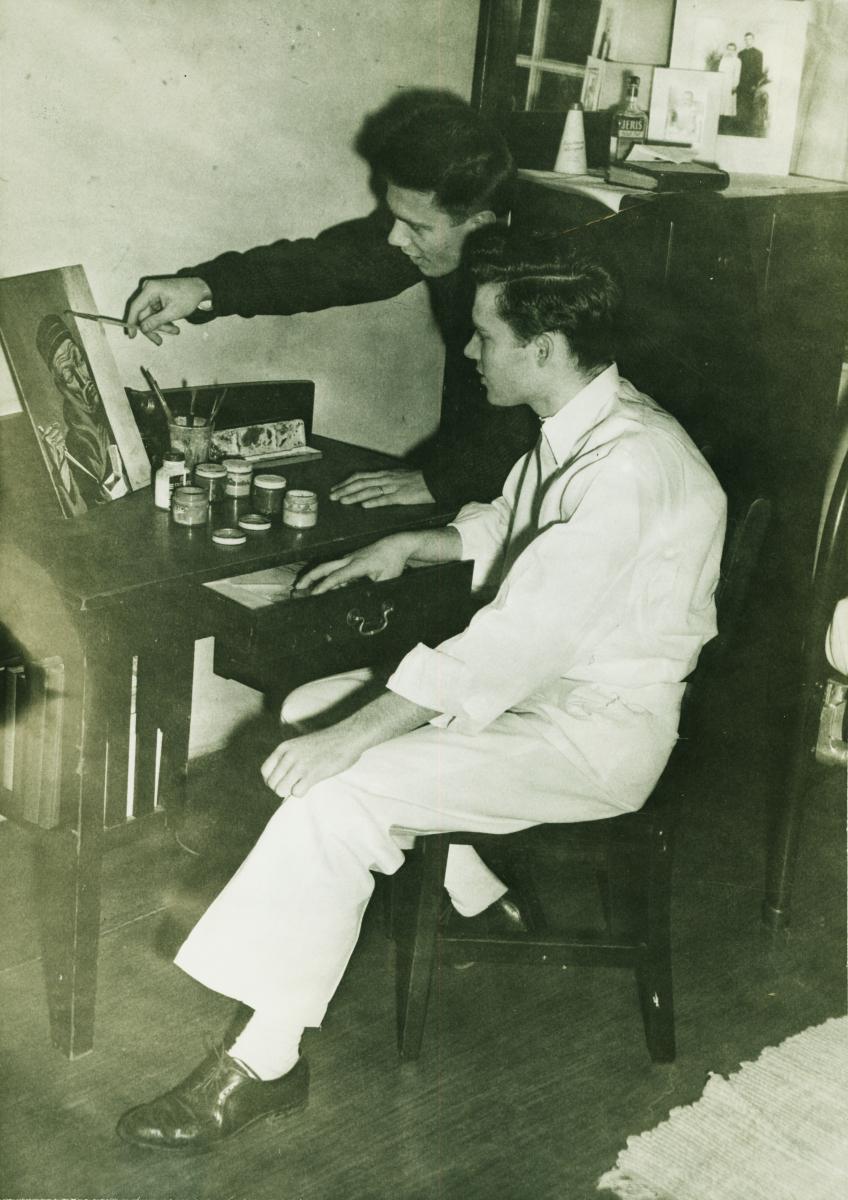

CPS Camp # 63, New Jersey State Hospital, Marlboro, New JerseyDon Jones and Paul Klassen doing art work, paintingca. 1945

CPS Camp # 63, New Jersey State Hospital, Marlboro, New JerseyDon Jones and Paul Klassen doing art work, paintingca. 1945 -

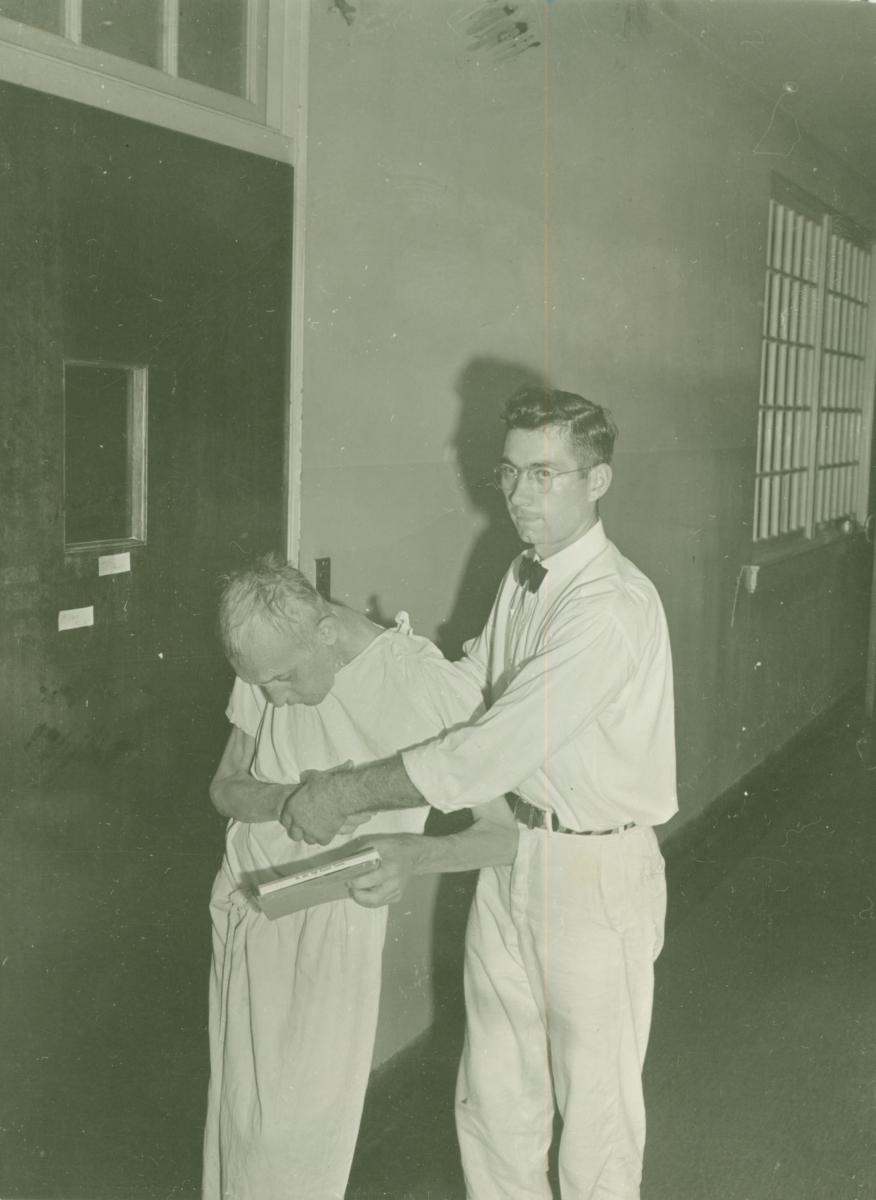

CPS Unit # 63, New Jersey State Hospital, Marlboro, New Jersey"Hospital II," Eric Kindy assisting patient to bedDigital Image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansasca. 1945

CPS Unit # 63, New Jersey State Hospital, Marlboro, New Jersey"Hospital II," Eric Kindy assisting patient to bedDigital Image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansasca. 1945 -

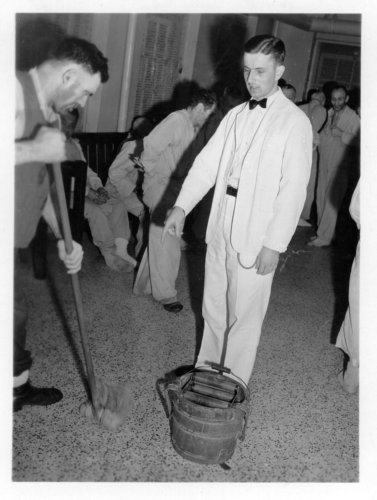

CPS Camp No. 63, New Jersey State Hospital, Marlboro, New Jersey.CPS Volunteer Paul Lichty directs clean-up at the mental hospital, circa 1945.Digital image, Photo #2225. Box 2, folder 3. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 63, New Jersey State Hospital, Marlboro, New Jersey.CPS Volunteer Paul Lichty directs clean-up at the mental hospital, circa 1945.Digital image, Photo #2225. Box 2, folder 3. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

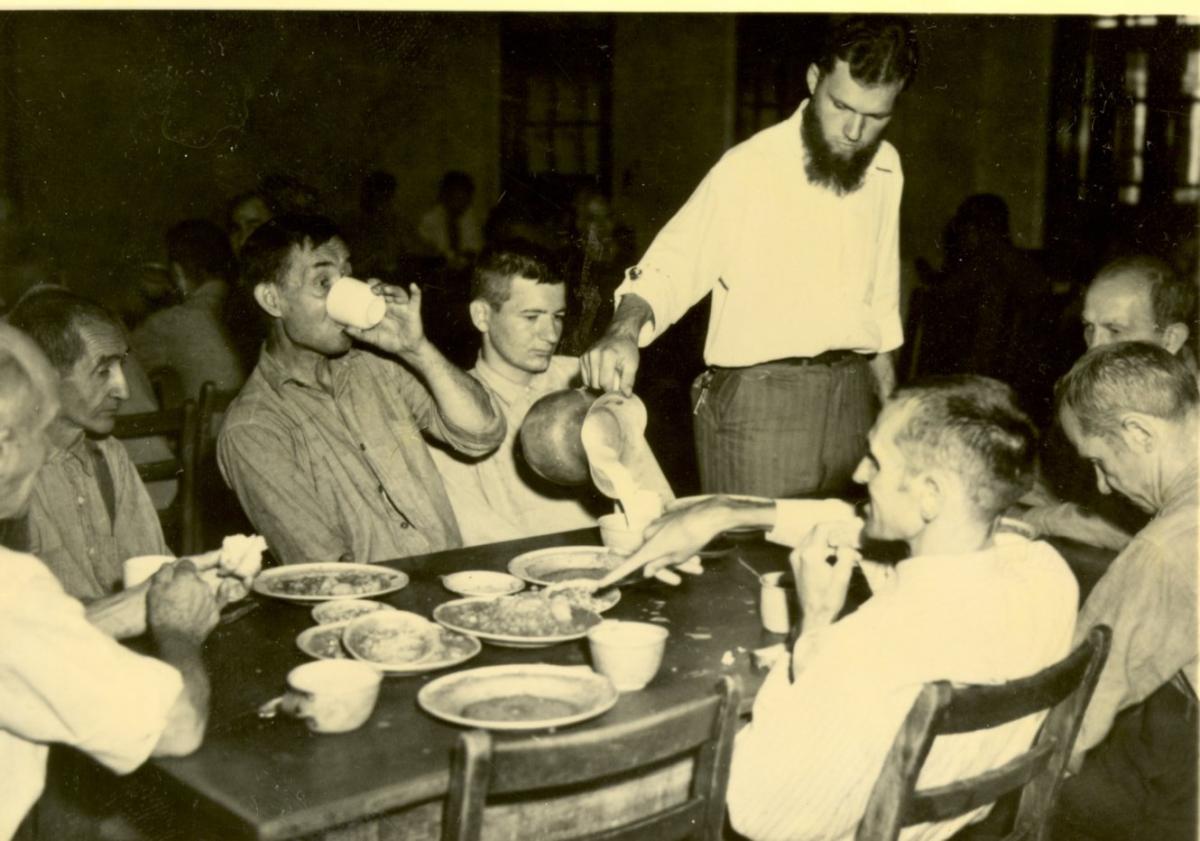

CPS Camp No. 63, New Jersey State Hospital, Marlboro, New Jersey.CPS worker serves patients at the mental hospital, circa 1945.Digital image, Photo #672. Box 2, Folder 3. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 63, New Jersey State Hospital, Marlboro, New Jersey.CPS worker serves patients at the mental hospital, circa 1945.Digital image, Photo #672. Box 2, Folder 3. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

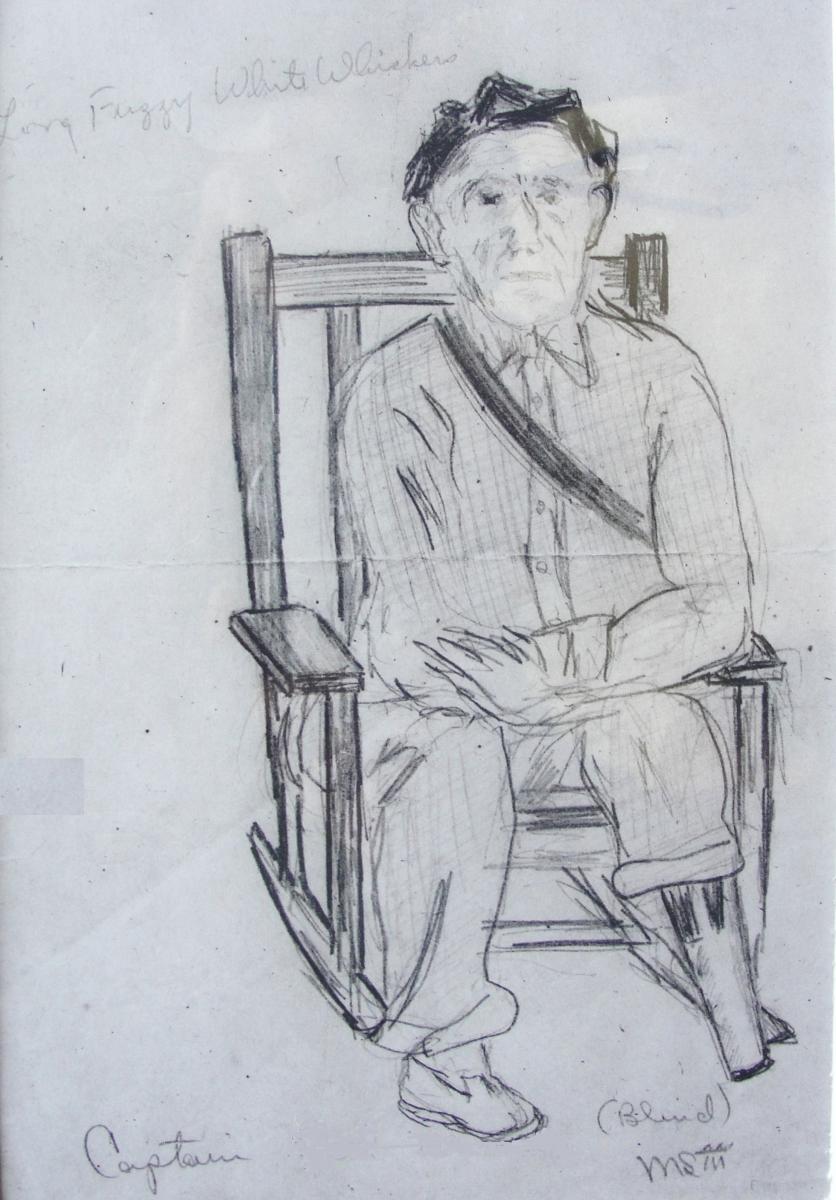

Captain ________*In the "day room" at New Jersey State Hospital. See "The Infestation: a reflection by Paul Klassen." *name withheld to protect confidentialityDrawing by Paul KlassenBetween 1943 and 1946

Captain ________*In the "day room" at New Jersey State Hospital. See "The Infestation: a reflection by Paul Klassen." *name withheld to protect confidentialityDrawing by Paul KlassenBetween 1943 and 1946 -

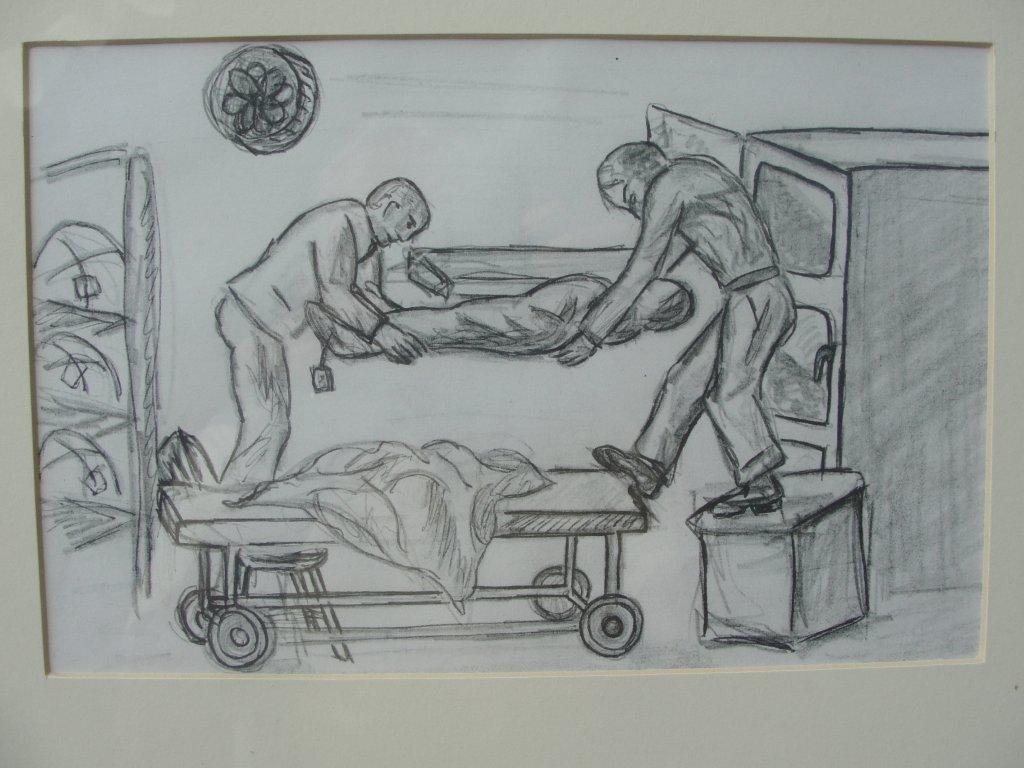

The MorgueTwo attendants placing the body of a deceased patient into the drawer in the morgue. We did this quite often, after tying a tag with the patient's name around his big toe and bundling his clothing into a sheet.Drawing by Paul Klassen

The MorgueTwo attendants placing the body of a deceased patient into the drawer in the morgue. We did this quite often, after tying a tag with the patient's name around his big toe and bundling his clothing into a sheet.Drawing by Paul Klassen -

Marie Martin checking weightMarie Martin checking weight at CPS Camp # 63, Marlboro, New Jersey. Marie Martin is probably the spouse of Harold Martin, Blue Ball, PA, or Landis Martin, Mountville, PA.Mennonite Central Committee Archival Photoca. 1945

Marie Martin checking weightMarie Martin checking weight at CPS Camp # 63, Marlboro, New Jersey. Marie Martin is probably the spouse of Harold Martin, Blue Ball, PA, or Landis Martin, Mountville, PA.Mennonite Central Committee Archival Photoca. 1945 -

Irene chuppIrene Chupp at her correspondence in the Marlboro State Hospital.Mennonite Central committee Archival Photoca. 945-1946

Irene chuppIrene Chupp at her correspondence in the Marlboro State Hospital.Mennonite Central committee Archival Photoca. 945-1946

-

ca. 1945

ca. 1945 -

ca. 1945

ca. 1945 -

ca. 1945

ca. 1945 -

-

-

Between 1943 and 1946

Between 1943 and 1946 -

-

ca. 1945

ca. 1945 -

ca. 945-1946

ca. 945-1946

CPS Unit No. 63, a Mental Hospital unit at New Jersey State Hospital in Marlboro, New Jersey operated by Mennonite Central Committee, opened in November 1942 and closed in October 1946. Most of the men served as ward attendants.

New Jersey State Hospital in Marlboro, New Jersey accepted the first CPS mental hospital unit in New Jersey.

In an effort to ensure favorable reception, prior to the arrival of the men, hospital leaders contacted the state American Legion along with local posts, as well as the state Civil Service Commission, to communicate the nature and purpose of the CPS unit.

Directors: Loris Habegger, Leonard Lichti, Roland Brown, Leo Miller

The medical director of the hospital personally selected the first twenty-five men from Medaryville, Indiana CPS Camp No 28 and Henry, Illinois CPS Camp No. 22. According to Selective Service regulations, men could not apply for transfer to detached service units until they had served ninety days at a base camp. The church committees and the National Service Board of Religious Objectors (NSBRO) first approved transfers, with final decision made by Selective Service.

Over the four years the unit grew to one hundred and three men, many married.

The majority of the men served as attendants, but a considerable number served in specialized jobs. As an example one of the men, Dr. Clarke T. Case, a graduate of Harvard Medical School, attended to sick patients. According to the hospital medical director Dr. J. Berkeley Gordon, Case “proved himself a well trained, competent man of sound judgment”. (Gingerich p. 222)

In general, CPS men were far more committed to patients and their care than were the war-time attendants staffing mental hospitals. Many of the regular attendants moved from place to place, and were not always dependable.

In a 1988 survey, one CPS man recalled that at the time of his arrival at Marlboro State Hospital, “the nursing staff was so distrustful of our presence that contrary to usual practice, no passkeys were issued to us for a period of six weeks after our arrival. . . . Finally, when they saw we could be trusted, we were given keys”. (in Sareyan p. 239)

Victor Goering, writing more than sixty years after his service at Marlboro, recalled the work.

We did not receive very much orientation but were put to work on the wards almost immediately. The hospital was grossly understaffed since the wages were very low. When the first CPS men arrived, some of the patients were carrying keys. There were a total of 3,000 patients scattered throughout the many wards. There were two buildings for patients who were considered dangerous and these patients were locked in prison-like cells. Most of the patients were housed in cottages that had beds for approximately 150 persons. African-Americans were segregated in two cottages – one for men and one for the women. . .

We worked seven days and then had the eighth day off. When your day off was on Saturday, you also got Sunday off. This gave us one day off each week. The daily shift was from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. with a two-hour break and thirty minutes off for two meals. This made a workday of nine hours and a work week of fifty-four hours. Our work consisted of keeping order, reporting illnesses, taking patients to the dining hall, and similar duties. . . . Those of us who were married and whose wives worked in the hospital were given living quarters above the patient’s wards. Elizabeth joined me in May after the school term was over and she also worked on the wards. A few wives were fortunate enough to get jobs as secretaries which, of course, was less strenuous than the ward work. (The Eden Peace Witness: A Collection of Personal Accounts pp. 104-110)

In the mental hospital units, the hospital superintendent was in charge of the CPS unit. In the case of the New Jersey State Hospital, Dr. Gordon, a former Navy official, was known for “running a tight ship”. Loris Habegger, the MCC unit assistant director did not always agree with Gordon’s manner but learned to offer his perspective in a deferential and diplomatic manner on decisions with which he disagreed.

While COs worked without pay, men in the unit were given the same consideration as regular hospital employees with respect to food, housing, facilities use, vacations and other compensation. This unit provided complete medical care to the assignees, their wives and children, including major operations, dental care, and replacement of glasses broken while on duty.

Marlboro, to help with the shortages in the women’s wards, employed fifty-eight CO wives in the unit. As they were not subject to Selective Service regulations, they received the regular pay for their work.

A Day Nursery project, established with some misgivings within the hospital administration, assisted the married men with children to provide care for babies while both parents worked. Twenty-nine children of COs from a few months to three years of age participated in the program partly staffed by CO wives. Goossen found in interviews with some of the women that after spending grueling twelve-hour shifts at the hospital, mothers rarely remained on the payroll more than a few months since they had so little time with their children. The arrangement did not lead to major difficulties for the hospital and proved helpful to the CPS men. (p. 61)

A major event in the life of the unit occurred when Eleanor Roosevelt visited on January 14, 1943. She inspected the hospital and visited with the CPS men.

The men published P.R.N., not unlike a college yearbook. It described the life of the patient as well as the work of the CPS men.

Richard (Dick) Hunter, a member of the unit, went on to work with associations that provided leadership in mental health care.

For more information on this unit and other mental health and training school units, see Melvin Gingerich, Service for Peace: A History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service. Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee printed by Herald Press, Scottdale, PA 1949, Chapter XVI, pp. 213-251.

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

See The Eden Peace Witness: A Collection of Personal Accounts edited by Jeffrey W. Koller. Moundridge, KS: Jebeko Publishing, 2004.

See also Alex Sareyan, The Turning Point: How Persons of Conscience Brought About Major Change in the Care of America’s Mentally Ill. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1994.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp publications database.

For more in depth treatment on CPS mental health and training school units, see Steven J. Taylor, Acts of Conscience: World War II, Mental Institutions, and Religious Objectors. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2009.