CPS Unit Number 054-01

Camp: 54

Unit ID: 1

Operating agency: ACCO

Opened: 10 1942

Closed: 2 1943

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 71

-

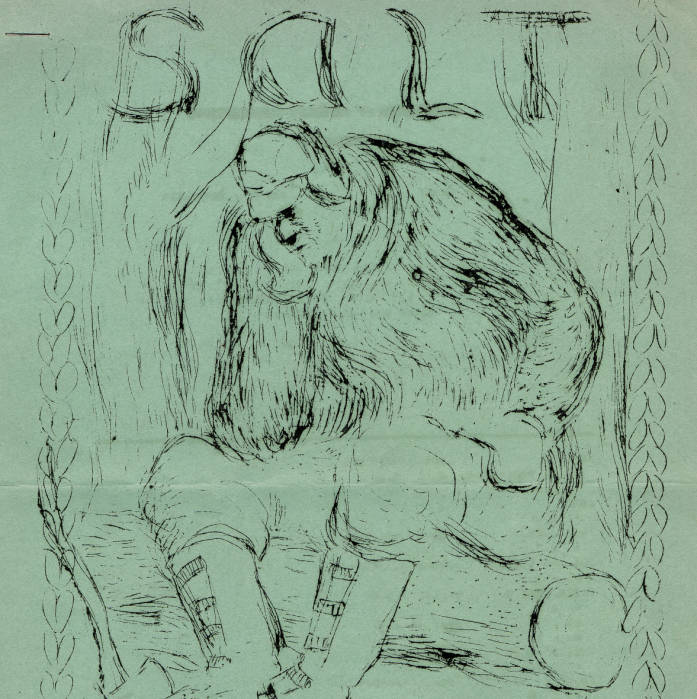

CPS Camp No. 54Salt was a newsletter published by the men of Camp 54. Only one issue was ever published due to a dispute over authority at the camp.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 54Salt was a newsletter published by the men of Camp 54. Only one issue was ever published due to a dispute over authority at the camp.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 54, a Forest Service base camp located in a former Civilian Conservation Corps camp near Warner, New Hampshire and operated by the Association of Catholic Conscientious Objectors (ACCO), opened in October 1942 and closed in February 1943. The men cleared debris remaining from the 1937 hurricane, cutting cordwood and clearing fire lanes. The camp closed within six months.

Located in south central New Hampshire, Warner included in its town boundaries Mount Kearsarge, 2937 feet elevation, and Rollins State Park. The Warner River flowed through the town, nearly ten miles from the CPS camp.

The Warner camp was located fifty miles from the earlier and smaller CPS camp No. 15 at Stoddard, which ACCO had operated as well. Stoddard remained open for a year with support from the AFSC New England camps, from which eight men transferred to increase Stoddard’s camp census.

The Stoddard and Warner camp men chose to call both camps Camp Simon, making a direct connection with Simon of Cyrene from the Bible (Matthew 27:89), as symbolic of “carrying the cross” of belief. (Zahn p. 23)

Director: Dwight Larrowe

Forty-five of seventy-five men who served at Camp Warner during the six months period of its existence had transferred from Stoddard, CPS Camp No. 15.

Of the seventy-five men at the camp, sixty-one identified as Catholics at point of induction, the remaining as Methodist, Unitarian, Friend, Episcopal, Orthodox, and one Jew reporting his affiliation with the War Resister’s League. According to Zahn, in practice, almost “one-quarter of the assignees were of non-Catholic persuasion or of no religion at all. . . . Of those who were classified as Catholics, a large number no longer practiced their faith and some were openly antagonistic to Catholicism, its teachings, and its behavioral expectations.”(p. 139)

Forty-eight of the men entered from the Middle Atlantic States (New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania), six from New England, and the remaining twenty-one from the Midwest (Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri and Ohio). Six percent came from cities of over one hundred thousand and slightly more than a quarter came from towns with populations of twenty-five thousand or less. Five men reported a rural or farm background.

All but six of the men ranged from 22– to 36-years of age at time of induction. Of the remaining six, three were 20 and the remaining three 37, 39 and 42 respectively.

Sixty-one men, or eighty-one percent of all the men at Warner had completed high school; forty-men, or fifty-seven percent, had completed some college. (Twenty-three of those were graduates, six held master’s degrees and one was awaiting his Ph.D.)

Fourteen of the men identified their occupation at time of induction as students, fourteen as working in clerical or managerial roles, thirteen men reported factory and general labor, eleven as artists and writers. Of those remaining, seven had worked in the service trades, six in civil service, and six had entered professional occupations in teaching and law.

One man was married and one reported himself as Negro. The married man left mid February 1943 to join the Air Force.

Men in the New England camps cleared debris remaining from the 1937 hurricane, which had created a serious fire hazard. At Warner, they cut dead trees and “leaners” into cordwood, mostly for camp use with the goal of one cord cut and stacked per day per four-man crew. However, inefficiency, inexperience and widespread malingering challenged goal accomplishment. (Zahn pp. 71-75) The often inclement weather with rain and snow contributed to slick axe handles, and work delays. The project superintendent and the foreman maintained reserved but friendly relations with the men, occasionally appealing to the director for assistance in improving production.

The men worked a forty-four hour week, in some seasons planting seedlings, digging waterholes or clearing fire lanes. They also performed camp maintenance duties as well as taking care of the garden and chickens after hours.

Gordon Zahn describes a pervasive sense of isolation at Camp Simon, ten miles from Warner and an additional distance from Concord, New Hampshire. Not only was the former CCC camp geographically isolated, but also the ACCO camps experienced psychological isolation from the Catholic Church. In fact many in the church hierarchy were openly hostile to conscientious objectors, directing spiritual and material support to men in uniform, each parish with its honor roll of soldiers. The Catholic Worker movement provided important and regular support to COs in the Catholic camps. (See Zahn Chapter 2, pp. 22-35)

Unlike the experience at Brethren, Friends and Mennonite camps where regular visitors spent time with the men as part of their educational and spiritual programs, only an occasional visitor made it to Warner.

Some of the men organized group activity centered on evening chapel services, after having converted a section of the former barracks school building into a tasteful center of worship. Occasionally an Irish priest attached to the New York Catholic Worker house of hospitality visited the camp.

On the other end of the same structure, the artists and writers set apart a studio for their activities. The men sketched, painted, talked, and sometimes drank along with a few of their non-artist friends.

The center third housed the camp library separating the two groups and providing space for reading, writing letters and journal entries.

Recreational activity tended to consist of spontaneous hikes, skiing, sledding, skating, pickup basketball or softball.

The combination of different beliefs about authority and governance among the men and the director, coupled with the absence of the director for the first few weeks after Warner opened, contributed to the many tension-filled meetings. The men transferring from Stoddard had settled into cliques and factions making it difficult to reach consensus. The same pattern soon emerged at Warner.

The difference in religious perspectives ranging from dissident agnostic intellectuals and atheists, to Friends absolutists, non-Catholic and non-practicing Catholic as well as Catholic liberals and rigorists, set the stage for often subtle clashes around, not only governance and authority, but also other aspects of camp life. Some defended Catholic identity and others feared manipulation by Catholic administration.

The men tried to function with a camp council that brought issues before the men. When they could not reach decision, then the camp administration would exercise authority in an “overly arbitrary manner. . .too much inclined to favor the Catholic campers”. (Zahn pp. 149) For fuller discussion, see Zahn pp. 144-154.

Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, visited the camp at a critical point after a particular period of internal turmoil amongst the various camp factions. Her talk coupled with a frank exchange in discussions acknowledged the men’s complaints about the CPS system (work without pay, poor food, authority in ACCO camps). She expressed her belief that the program represented too much of a compromise with the war effort. Yet she affirmed her support for the CPS men as making a more effective witness than those in noncombatant service, because the latter shared

. . .in the honor and glory lavished upon the soldier; the men in CPS, isolated and frustrated though they might be, could at least enjoy the satisfaction of knowing they were more of a problem for the government if only in that the very fact of their existence disturbed the unanimity of a nation committed to war. (Zahn, p. 186)

Since this and the other Association of Catholic Conscientious Objector camps relied on the readers of Catholic Worker for financial support, the camp went without professional nursing care. In addition, camps appealed to the same readers to fund any dental or medical appointments. Fortunately the camp experienced no serious injuries, although a high proportion of the men found themselves sick, adding up to 1,200 sick-days, or 13.9 percent of the total days at Warner. (Zahn p. 155)

The men did not always eat well, particularly after they had used up the stored produce and meat brought from Stoddard. Catholic Worker standards of voluntary poverty assumed simple meals of bread and soup, low grade meats, and donated staples and food stuffs. That coupled with insufficient funding for the camp in general, created regular food shortages which became severe. Neighboring CPS camps often made contributions to Warner as the CPS system, highly concerned, did its best to help out. Several Brethren camps regularly contributed funds raised by men voluntarily skipping meals in those camps. Families and friends sent packages which some men shared while others hoarded. Some raided the pantry, others petitioned the National Service Board of Religious Objectors and Selective Service for an investigation of the food situation. Selective Service did inspect camp conditions and found dietary deficiencies, a finding which contributed to the decision to close the camp.

On occasion, the men did travel to Concord for weekend visits. They reported an enjoyable Halloween dance sponsored by some Boston pacifists. Those from the Northeast could make weekend visits home. The camp hosted a weekend visit for a group of Smith College women, replete with good meals, dancing and an evening program with skits written for the occasion. Some of the men returned the trip to Northampton in early March shortly before Camp Simon closed.

Of the twenty-five men who remained at the camp for that early March weekend while a blizzard raged, eleven set out for a wild night of bingeing in Concord. Warner had been known for its occasional periodic alcoholic indulgence to combat the boredom and monotony of camp life.

The men published one issue of a camp paper, Salt, the same title selected by the men in CPS Camp No. 15 at Stoddard, New Hampshire. It should be noted that the one Warner issue resulted in an open dispute over doctrine and authority in the camp, and few copies were ever distributed. The men published two issues of Salt while at the Stoddard camp.

The camp was closed citing the work project as not being important enough to maintain coupled with insufficient food for the men. Zahn also noted that the camp lacked any support from the diocese, which had vigorously stated its position that men should join the war effort.

When the camp closed, the majority of the men transferred for a short term to AFSC Forest Service Camp No. 89 at Oakland, Maryland or to the AFSC Farm Security Administration Camp No. 94 at Trenton, North Dakota. When the ACCO CPS Unit No. 102 opened in May 1943 at the Rosewood State Training School for the Mentally Retarded in Owings Mills, Maryland, a number transferred there, thus continuing their service in a Catholic affiliated camp.

Before the end of the war, sixteen of the men from Warner had requested reclassification from CO status to eligibility for military service, and five were discharged as physically unfit.

For general information on CPS see Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 1990.

For information on CO protests that pay for work might be directed to war efforts, see Steven Nolt, “The CPS Frozen Fund: The Beginning of Peacetime Interaction Between Historical Peace Churches and the United States Government,” Mennonite Quarterly Review, 67 (April 1993), 201-224.

For an in depth history of conscientious objection in the United States, see Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-1947. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.

Gordon C. Zahn, Another Part of the War: The Camp Simon Story. Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1979.