CPS Unit Number 053-01

Camp: 53

Unit ID: 1

Operating agency: AFSC

Opened: 10 1942

Closed: 4 1943

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 178

-

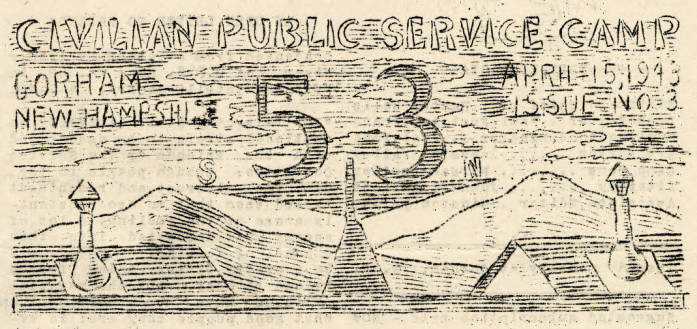

CPS Camp No. 5353 was a newsletter published by the men at Camp 53 from January to April 1943.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 5353 was a newsletter published by the men at Camp 53 from January to April 1943.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 53, a Forest Service base camp located in the White Mountain National Forest near Gorham, New Hampshire and operated by the American Friends Service Committee, opened in October 1942 and closed in April 1943. The men performed timber management, fire control, and maintenance of trails, highways and telephone lines.

CPS Camp No. 53, a Forest Service base camp was located in an old CCC camp “situated on the side of the mountains known as Carter Dome. It was a pretty crude affair. . . .” Within the White Mountain National Forest near Gorham, New Hampshire, it could accommodate 150 men. (from Mullin letter) Operated by the American Friends Service Committee, the camp opened in October 1942 and closed in April 1943.

Excerpts from Mullin’s December 1943 letter to family follow.

The buildings had been built in 1934 before the government had had much experience with C.C.C. camps. There were four barracks or dormitories each accommodating 40 men. There was a dining hall, a recreation hall, an education building, administration building, supply house, infirmary or hospital, and numerous forestry buildings such as tool shed, carpenter shop, blacksmith shop, machanics [mechanics] shop and numerous garage stalls for equipment—oh yes, I forgot the bake house, the wash house, and the latrine which fellows said they had to run a mile to at night in sub-zero weather. It was very inconveniently placed at one end of the camp grounds. (p. 2)

I might mention that the area around the camp was totally uninhabited, with the exception of a Mountain Lodge of the Appalachian Mountain Club some five miles south and the town of Gorham six miles north. There was nothing but mountains to the East & West—no farm house or human habitation & to get lost or frozen up a mountain trail would be a real tragedy for anyone. (p. 8)

Mullin also reported on changes that needed to be made to accommodate women at the camp, who were his wife as well as the nurse and dietician.

Director: James Mullin

Dietician: Mary Lydon

Nurse: Ann Richardson

By April, 1943 the Gorham camp roster included one hundred and thirty-nine men, with twenty in detached service units. The men came from fifteen states and represented thirty-seven colleges and universities; their average age was twenty-six; eighteen men were married.

While twenty-five of the men reported church affiliation as Friends, twenty-eight men reported no affiliation. The remaining men reported affiliation with twenty-five different denominational groups.

Education levels varied. Eleven men had completed eighth grade or less, another eleven less than four years of high school, and thirty-two had completed high school; thirty-one had completed one to three years of college, and forty-two had graduated from college; ten reported post graduate experience and nine had completed post graduate work. Twenty-one men entered CPS with trade school educational experience.

“Men worked in the woods about five miles from the camp every day all winter except Sundays and Christmas and six other days when it was either too rainy or too cold. Day after day they went out when it was 15 and 20 below [zero]. They would have noon lunch on the job, building a fire in the snow to heat the soup. I’ve been out when the wind was so high and it was so cold that sandwiches had to be eaten with heavy gloves and mittens on for fear of freezing ones fingers—and when the cups & spoons—aluminum—would take the skin off of one’s hands when touching them.” (Mullin, p. 3)

A crew of fifty to sixty men cut cordwood to remove dead and diseased trees in order to encourage growth of young trees in the forest. This timber management allowed a good crop of trees to mature into saw logs in fifteen to twenty years. The camp used the by-product cordwood for heat and to supply families on relief in Coos County. Mullin describes the circumstances.

During December (1942) we had run up against a difficult problem in connection with our project work. During the winter time the only thing—and the appropriate thing—to do is cut wood in the forest. That is the right time of year to do it—when the sap is low in the trees, when the logs can be skidded down the mountains, and when there are no black flies to pester the worker.

The men in camp immediately raised the question about who would get the wood—whether is [it] was to be shipped directly to the army or to the plant—such as Brown Co. in Berlin—a paper company which was extracting chemicals from wood for use in working high explosives for the army.

After negotiations with the Supervisor of the Forest in Laconia, N. H. and the local administrator of relief in Berlin, we worked out a plan whereby the wood we cut would become the property of the local relief agency to be distributed to poor families in that industrial area who could not afford to buy it. This was a strategic move for it increased our morale 95% and bettered our community relations. . . . We had promised forestry men an increase of 25% in production over December and by mid March we had far exceeded that.

Our relations with the supervisory personnel of forestry service improved as it became clear what a marked difference the meaning and purpose of the work made to the men. We had good men as foreman—the head guy—the Superintendent was pretty tough to get along with—a hard headed fellow with quite a deep inferiority complex which resulted in a “chip-on-the-shoulder” attitude most of the time. Furthermore, he couldn’t get used to so many professional men—college men—engineers, foresters, etc. working for him all the time and wanting to know “why” about so many things. (pp. 9-10)

The men assisted about two hundred families in the county, since the paper mill in Berlin, some distance away, had not been able to meet the demand due to labor shortage. (Newsletter March 3, 1943)

The men prepared tools for fire season and trained on the use of the equipment. They installed water collection tanks on lookout towers. They relocated a state lookout tower no longer needed by the Forest Service. Since some timber damage remained from the 1938 hurricane causing a serious fire hazard, the men continued to clear the damage.

Work crews also maintained the Dolly Copp Tuckerman Ravine shelter, Glen Ellis Falls and other recreation areas.

Excerpts from Mullin’s letter describe aspects of camp life.

We ate our meals in the main dining hall with all the men. Breakfast was at 6:30 AM. Lunch was at 12 and Dinner at 5:30. At first our meals were not so good. Our dietitian, a highly trained one, found it difficult to get things she needed. She finally worked out a plan whereby she got the large wholesale houses in Boston to arrange for deliveries right to the camp. The main highway near the camp was kept open the year around and soon we found we were able to get plenty of food and have a good balanced diet. Both Swift and Armours maintained stations in Berlin 12 miles away and we were able to get some meats now and then. We used oleo Margarine, of course, all the time. We had plenty of milk and eggs and fresh vegetables all the time & we arranged with a Florida concern to ship oranges and grapefruit to us directly so we had citrus fruit almost every morning.

We had a bake house just outside the kitchen. Four men were assigned to that job—2 working long hours every other day—making it possible for us to have all the home-made whole wheat, rye, cracked wheat—any kind of bread and biscuits, pies & cakes any time. (p. 5)

Mullin also reported that the camp evening program included classes, discussions, committee meetings, council meetings “crowded on top of program of personal conferences” with the 150 men. (p. 11)

From January through April 1943, the men published a paper called 53. With an editorial staff of six men, the newsletter featured not only local camp news but also reported on issues of concern across CPS. The banner headline of Issue No. 3, “21 MEN TO OREGON”, reported on the desire to increase capacity of CPS. Camp No. 59 at Elkton, Oregon, and that Philadelphia had asked for thirty-eight men from Gorham.

Two men, Robert Brill and George Cole, presented their opinions on the conscription of women for war in the April 15, 1943 issue of 53.

In the same issue, the editors included “An Open Letter to Friends” written by Arthur Wiser from the April 3, 1943 issue of Friends Intelligencer published by CPS Camp No. 32 at West Campton, New Hampshire. “In this camp it is literally an emotional strain to be associated with the Friends or the Service Committee. Enough people in this camp feel distrust and resentment toward them that we are constantly aware of the feeling. That would be a pretty bitter thing for a Friend to hear.”

The letter reported frustration over not being able to do more meaningful work, that the majority of Friends men chose serving in the armed forces, guilt over difficulty in building a pacifist community, rising public opinion against COs, and increasing dissatisfaction in the camps. Wiser closed with suggestions for ways in which the Friends Service Committee could be more supportive of CPS men.

According to the March, 1943 issue of the camp paper, some of the men enjoyed a day of outdoor recreation, hiking and picknicking with a dozen or more women visitors from Smith College and Radcliffe College in Massachusetts. They closed the evening with vesper services and fireside singing.

Considerable confusion arose over the closing of the camp, and the men learned on April 25th of the closing date of May 1. “When May 1st came, special coaches were waiting at the station and by a masterful job of planning and coordination we had all baggage and equipment and 110 men at the station at 8 AM.” (Mullin p. 12) A last group of men stayed to finish cleaning the camp before leaving for West Campton, CPS Camp No. 32. Dietician May Lydon moved on to Gatlinburg, Tennessee to serve as dietician at CPS Camp No. 108. One fourth of the men went to San Dimas, California, CPS Camp No. 2, another fourth to Coleville, California CPS Camp No. 37, one fourth to Elkton, Oregon CPS Camp No. 59, and the rest to West Campton.

53, No. 2 (March 7, 1943); No. 3 (April 15, 1943) in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Section 3, Box 12.

For general information on CPS camps see Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. Intercourse, PA: Good Books 1990.

James P. Mullin, journal/letter sent from Drexel Hill, PA to family in Indiana, 1943. Hand written with photographs on some pages; typed by daughter, Martha (Marty) Mullin in 2010.

For an in depth history of conscientious objection in the United States, see Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-1947,. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.