CPS Unit Number 045-01

Camp: 45

Unit ID: 1

Title: Shenandoah National Park

Operating agency: MCC

Opened: 8 1942

Closed: 7 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 576

-

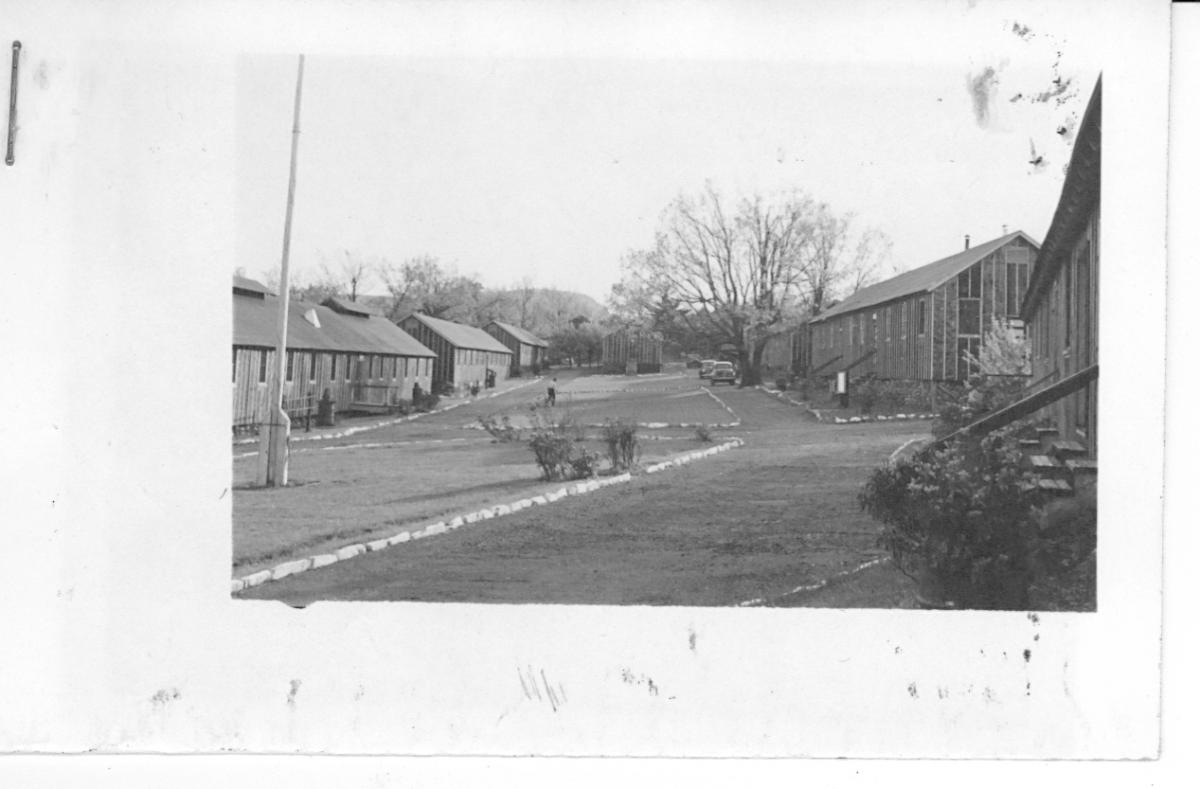

CPS Camp No. 45, Luray, Virginia1946. Luray, Virginia. Civilian Public Service camp 45, Luray, Virginia, Shenandoah National Park.Mennonite Community Photographs, 1947-1953: Service. HM4-134 Box 1 Photo021.1-4. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 45, Luray, Virginia1946. Luray, Virginia. Civilian Public Service camp 45, Luray, Virginia, Shenandoah National Park.Mennonite Community Photographs, 1947-1953: Service. HM4-134 Box 1 Photo021.1-4. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

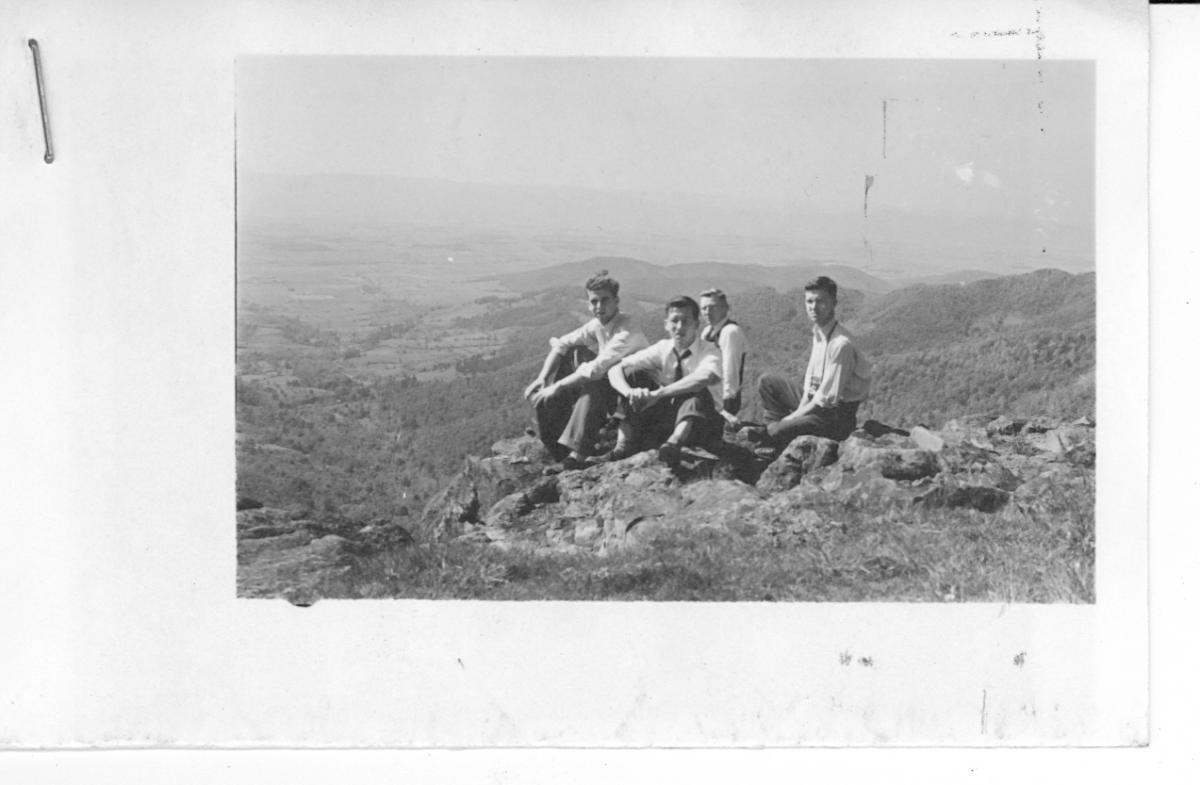

CPS Camp No. 45, Luray, VirginiaMay, 1946. Luray, Virginia. Civilian Public Service hikers.Mennonite Community Photographs, 1947-1953: Service. HM4-134 Box 1 Photo 021.1-3. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 45, Luray, VirginiaMay, 1946. Luray, Virginia. Civilian Public Service hikers.Mennonite Community Photographs, 1947-1953: Service. HM4-134 Box 1 Photo 021.1-3. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

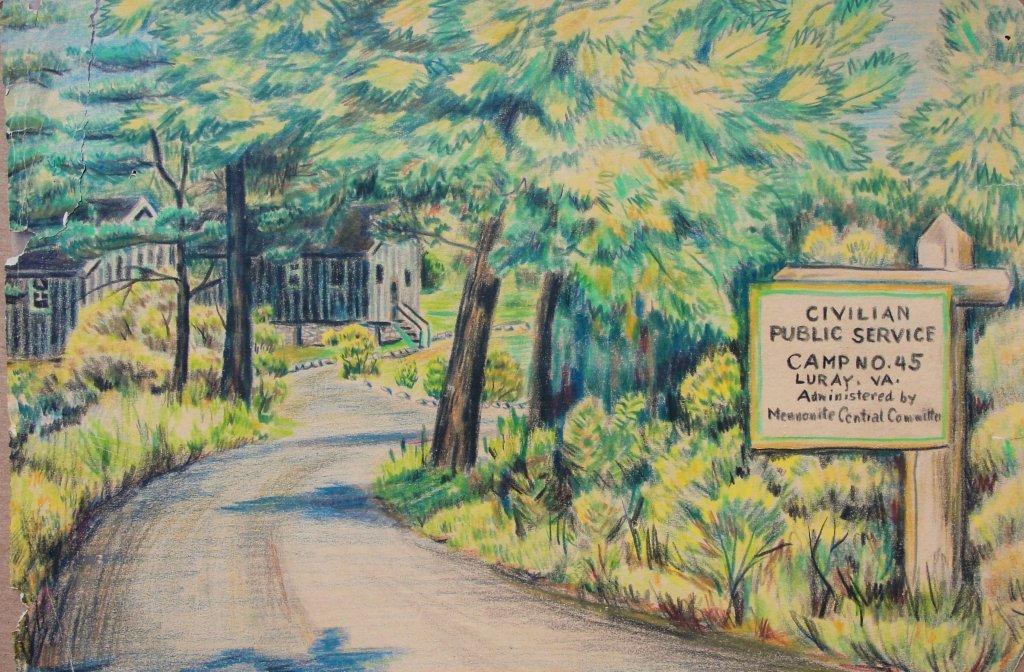

CPS Camp No. 45, Luray, VirginiaLuray Camp entranceDrawing by Paul Klassen

CPS Camp No. 45, Luray, VirginiaLuray Camp entranceDrawing by Paul Klassen -

CPS Camp No. 45Civilian Public Service camp 45, Luray, Virginia. Hogbuck - fire lookout tower built by C.P.S.Box 1, Folder 26. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 45Civilian Public Service camp 45, Luray, Virginia. Hogbuck - fire lookout tower built by C.P.S.Box 1, Folder 26. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 45Civilian Public Service camp, Luray, Virginia. Laundry boys.Box 1, Folder 26. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 45Civilian Public Service camp, Luray, Virginia. Laundry boys.Box 1, Folder 26. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 45Civilian Public Service camp 45, Luray, Virginia. Late Sunday P.M. recreation period.Box 1, Folder 26. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 45Civilian Public Service camp 45, Luray, Virginia. Late Sunday P.M. recreation period.Box 1, Folder 26. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "Walking back to truck after a day on blister rust control work."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "Walking back to truck after a day on blister rust control work."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens -

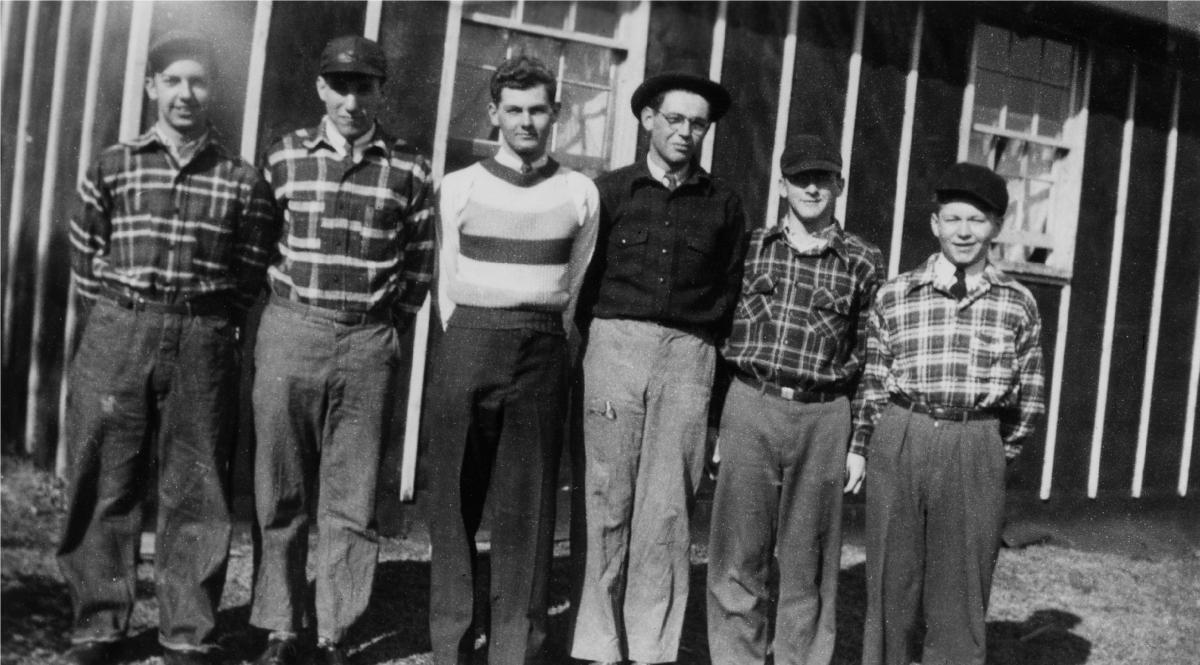

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "At Luray C.P.S. camp from left to right Willard Hunsberger, Lester Tyson, Kenneth Bauman, Bob Nyce, Earl Hensel, me."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "At Luray C.P.S. camp from left to right Willard Hunsberger, Lester Tyson, Kenneth Bauman, Bob Nyce, Earl Hensel, me."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens -

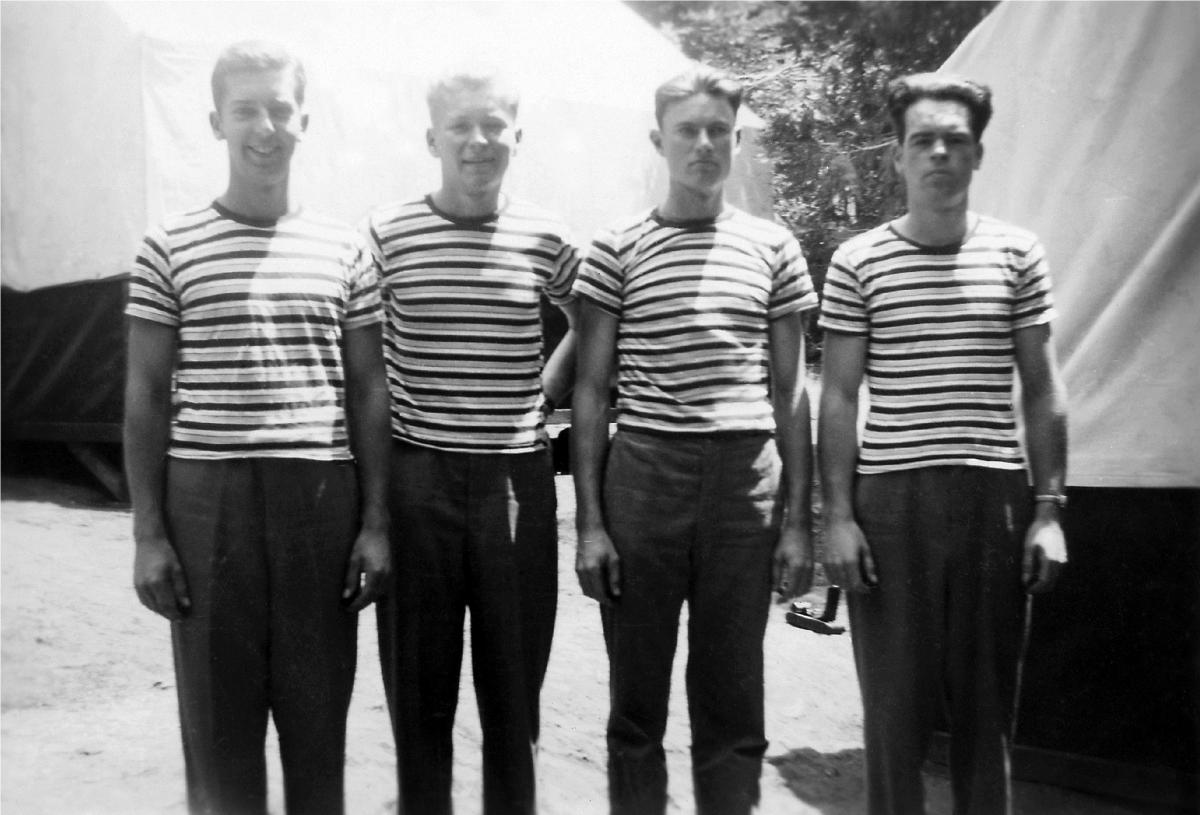

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "The quartet, from l to r. Willard, me, Mark Duerksen, and Dick Delp."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "The quartet, from l to r. Willard, me, Mark Duerksen, and Dick Delp."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens -

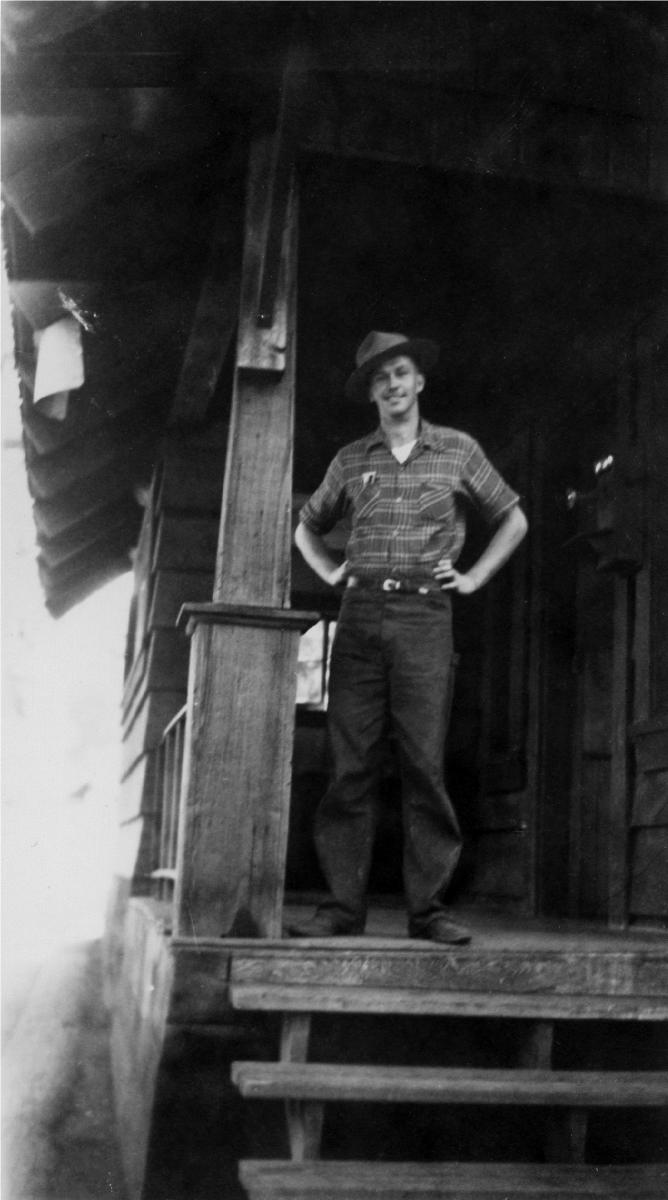

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "Abed Jantz, cook who came down to the Grant Grove Range Station."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "Abed Jantz, cook who came down to the Grant Grove Range Station."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens -

CPS Camp No. 45Old Rag Lookout.Photo by Edgar M. Clemens

CPS Camp No. 45Old Rag Lookout.Photo by Edgar M. Clemens -

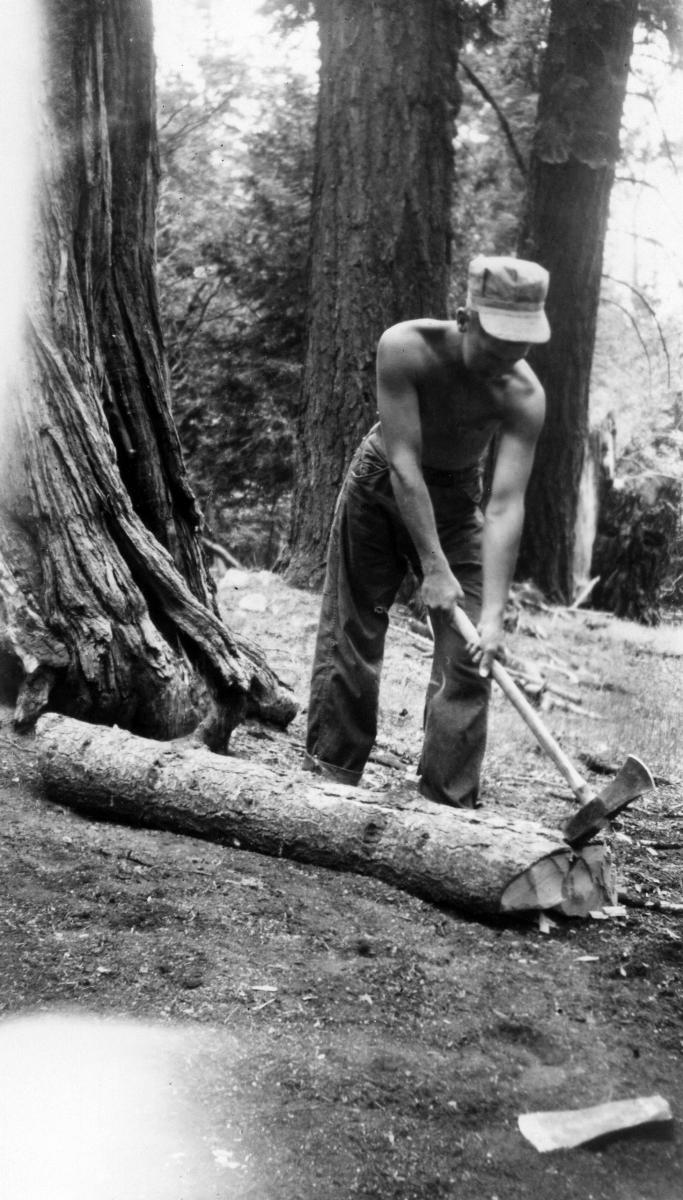

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "W. Hunsberger, splitting wood around camp."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "W. Hunsberger, splitting wood around camp."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens -

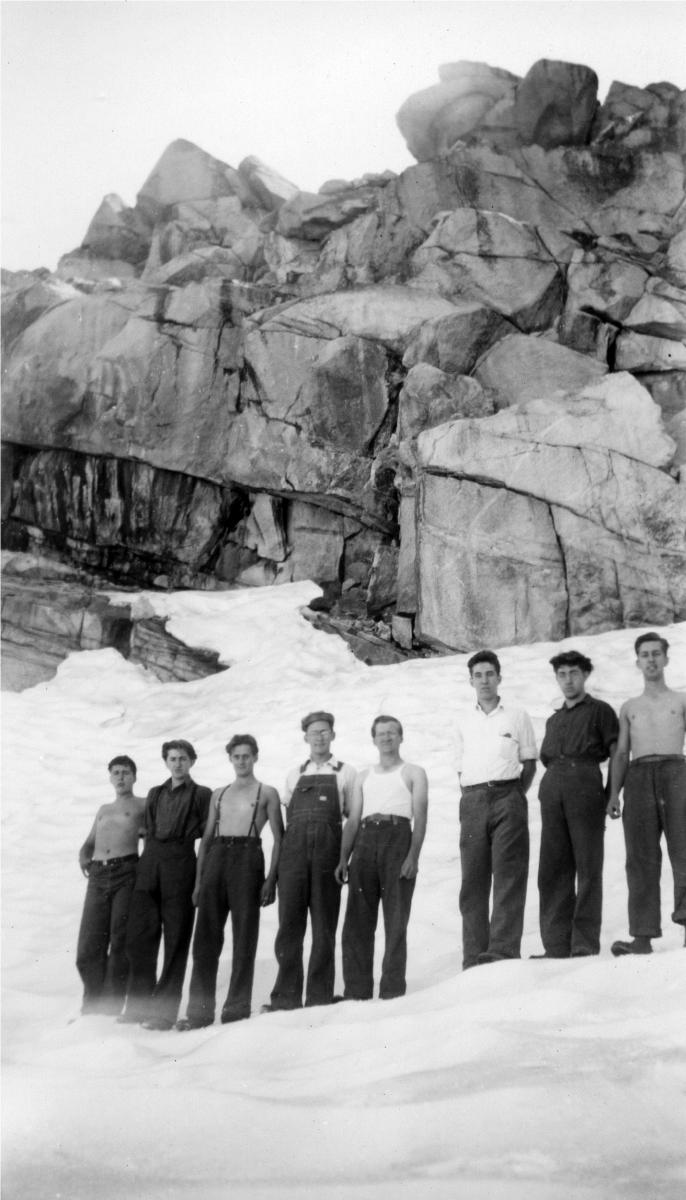

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "In the snow at Alto Peak. Left to right--Clarance Miller, Menno Beechy, Dave Yoder, Earl Hensel, Mose Yoder, Lester Tyson, Roman Beechy, Willard Hunsberger."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens

CPS Camp No. 45Caption on back of photo reads: "In the snow at Alto Peak. Left to right--Clarance Miller, Menno Beechy, Dave Yoder, Earl Hensel, Mose Yoder, Lester Tyson, Roman Beechy, Willard Hunsberger."Photo by Edgar M. Clemens -

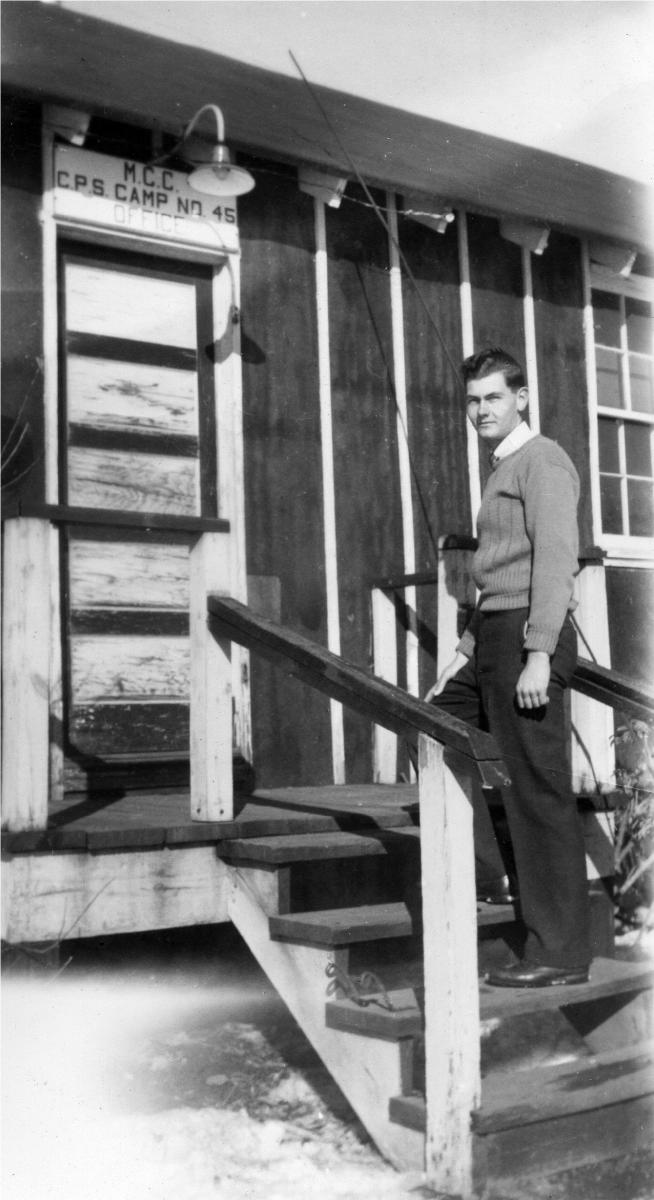

CPS Camp No. 45Kenneth Bauman outside the office of camp #45 in Luray, Virginia.Photo by Edgar M. Clemens

CPS Camp No. 45Kenneth Bauman outside the office of camp #45 in Luray, Virginia.Photo by Edgar M. Clemens -

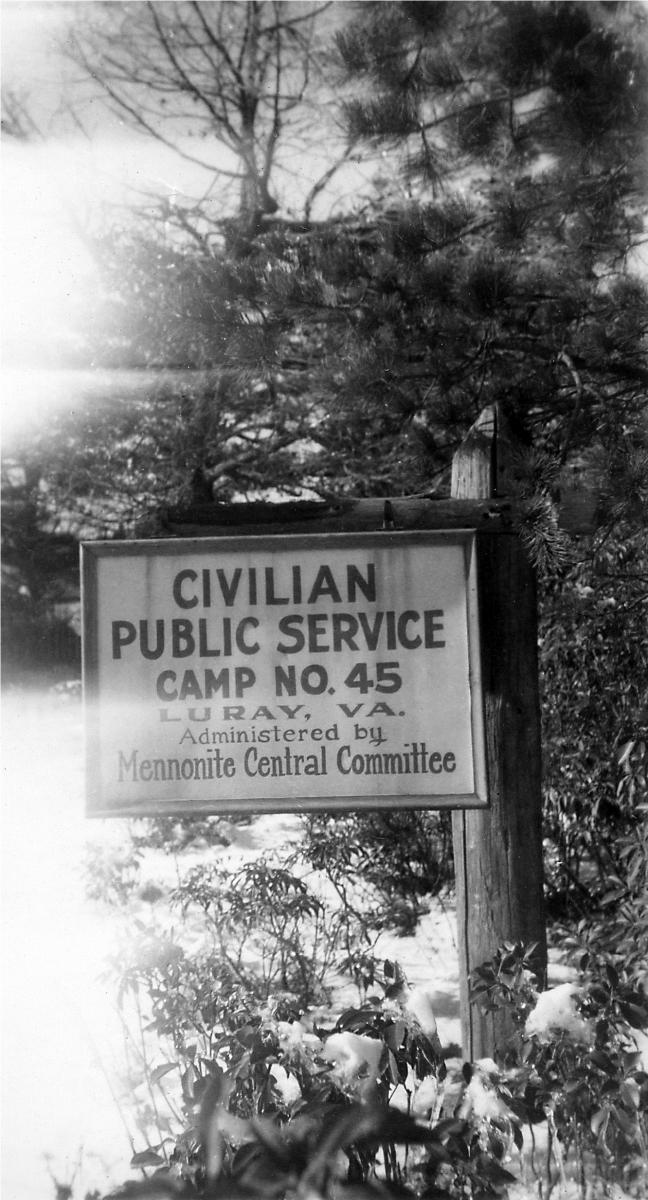

CPS Camp No. 45Sign for camp #45 in Luray, Virginia.Photo by Edgar M. Clemens

CPS Camp No. 45Sign for camp #45 in Luray, Virginia.Photo by Edgar M. Clemens

CPS Camp No. 45, a National Park Service base camp located in Shenandoah National Park near Luray, Virginia and operated by the Mennonite Central Committee, opened in August 1942 and closed in July 1946. Men maintained and improved park and recreational facilities, including roads. They also performed conservation and fire prevention duties.

Located near the center of the Shenandoah National Park, this camp was four miles north of Stony Man Mountain peak at 4,010 feet elevation and just west of Skyline Drive. Luray was about fifteen miles northwest of the camp. The Appalachian Trail passed near the camp so the camp was often visited by travelers on both Skyline Drive and trail.

Directors: Glen Whitaker, Dwight Yoder, Paul Guengerich, S. Glenn Esh, Ralph Lehman

Dieticians: Vella Burkholder, Laura Blosser, Naomi Weber, Mary E. Wenger

Matron: Mrs. Glen Whitaker

Nurse-Matrons: Katherine Derksen, Margaret Reimer, Kathryn M. Yoder

Nurse: Vera Yoder

The unit quickly grew to one hundred fifty men. The campers reported greater diversity in denominational affiliation upon entering CPS than was typical in MCC camps, with twenty-five percent of the men reporting affiliations other than Mennonite. Some reported no religious affiliation. Fourteen men who transferred in from a Friends camp in New Hampshire helped expand the camp educational program and boost morale.

The Selective Service order for this camp stated the work as. . .

consisting of construction, improvement and maintenance of park and recreational facilities, including roads, trails, utilities and park structures, the restoration, conservation and protection of natural resources by reforestation, erosion control, fire suppression and presupression, grading, sloping banks, planting, seeding, sodding, and completion of the construction of an underground telephone system. . ..(as cited in Gingerich p. 150).

The men not only worked in the areas identified above, but also undertook other projects. One, a wildlife survey, covered three hundred thirty-six miles of unblazed trail to estimate the number of deer, rabbits, foxes, wild turkeys, squirrel, grouse, groundhogs, and wild cats for the park’s annual report.

In another project, men worked to control blister rust, which attacked white pines and was transmitted by wild gooseberry bushes. They pulled apart bushes, uprooted them, and treated any remaining roots with salt. The “gooseberry gang” would average four hundred a day and they had to rework the area if too many feet of live stem remained.

The construction crew erected a fire lookout tower and living quarters on Hogback Mountain, elevation 3,474 feet, seventeen miles from the camp. They also began a lookout tower on Old Rag Mountain where they hauled materials one and two tenths miles up a forty-five degree grade to the site on top of the mountain.

They maintained the National Park Headquarters located five miles east of Luray, tended horses for riding in the park, painted signs for Skyline Drive, drew maps, mapped Skyland (a summer resort in the park), and checked park grounds. Men also manually removed snow from the highway and around buildings, even though snowplows were available.

The chief purpose for the camp, however, was to provide fire-fighting for the park. The men, organized into crews of twenty-five men each, took turns on fire duty, all subject to immediate call. They trained on techniques for fighting eastern fires and drilled in the use of various tools. Ten men trained for lookout tower service. The amount of time fighting fires was less than in the western camps, “855 [person] days were devoted to this task in four years and 3,915 [person] days were given to fire presuppression”. (Gingerich p. 154) The men also contributed 3,096 days to emergency farm labor by thinning acres of corn.

Since demand for manpower on farms and in areas of human need was so high during the war, the men questioned “the national importance” of much of the camp work. It should be noted that the opportunity to transfer to a different camp generally improved assignee morale. However, losing well trained men created some on-going tension with Park Service supervisors. After twenty-seven men (of thirty-one volunteers) were released to Camp Belton, Montana in late April, relations were somewhat strained with Park Service supervisors. All were invited to a Thanksgiving meal and evening program to ease those tensions.

Other men transferred from time to time to training schools and mental hospital units, with a group of thirty-five (twelve volunteers and the remainder by lottery) answering the May 1945 call to meet camp needs at Three Rivers, California.

In general the CPS men enjoyed good public relations, partly because they were located far from neighbors, but also because they provided emergency assistance on farms. National Park Service reports indicate high appreciation for the thrift, hard work and skill of the assignees.

Dwight Yoder wrote over sixty years later about his Luray experience.

In a camp of 140 to 150 men living and working together, some disgruntled and unhappy, there were bound to be many interesting and some not so interesting experiences. One camper, unhappy with me, nailed my hat to the dormitory wall. Many years later he wrote me a letter confessing he was the culprit, but added “I never had so much fun in my life.”

Another camper had the habit of playing sick on work days. One day our astute nurse, Vera Yoder, gave him a big glass of orange juice heavily laced with castor oil. He was the busiest man in the camp that day.

An older camper offered my $500 to arrange his discharge. Of course, I could not or would not do that.

The intellectual life of the camp burgeoned when a Quaker camp was closed and our ranks swelled by men from there, all of whom had graduate degrees. A very colorful camper was Dr. Herbert Zim of New York City, a scientist and author and an objector on humanitarian grounds. (“Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories, pp. 68-70)

The camp educational program included several special schools—an arts and crafts institute conducted by Professor J. P. Klassen of Bluffton College, a conscientious objector in Russia during WWI; a Christian life conference conducted by B. B. King of Elida, OH; and discussions on Mennonite history and the Mennonite peace principle conducted by Dr. C. Henry Smith.

Mrs. Harry Wenger conducted a cooking school attended by thirteen men from five camps. The men took classes and completed four hours of supervised work in different components of the camp kitchen under experienced CPS cooks. After seven weeks, the school prepared a banquet following which the camp chorus sang and the Chief Park Ranger Wallace T. Stephens spoke.

A camp chorus under the leadership of Dwight Weldy performed a series of concerts in Mennonite schools and Brethren churches. Newton Weber of Harrisonburg, Virginia and Titus Book preached regularly at the camp.

James R. Clemens became “educational director while at Luray, responsible for the library, education and social programs and sponsor of the camp paper The Skyliner.“ Men published the paper from January 1943 through March 1946. The Skyliner reportedly not only included well written articles and provided good coverage of camp work and life, but also contained excellent art work. (“Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories p. 11-12)

For more information on Camp Luray and work in National Park service see Melvin Gingerich, Service for Peace: A History of Mennonite Civilian Service. by Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee printed by Herald Press, Scottdale, PA 1949, Chapter XII p. 149-161.

See Kevin Grange, “In Good Conscience”, National Parks (Winter 2011) http://www.ncpa.org/magazine/2011/winter/in-good-conscience.html?

For general information on CPS camps see Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. Intercourse, PA: Good Books 1990.

For personal stories of CPS men, see Peace Committee and Seniors for Peace Coordinating Committee of the College Mennonite Church of Goshen, Indiana, “Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories. Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1995, 2000.

For a story of one couple’s long engagement during CPS, including photos and love letters during a period of a long deferred marriage, see Redeemed, A Reflective Chronology of the Lives of Fred E. Augsburger and Carolyn King Augsburger by Ruth Ann Augsburger and Owen E. Burkholder, www.orabooks.com, 2011. The book can also be found at The Menno Simons Library at Eastern Mennonite University, Harrisonburg, VA.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.