CPS Unit Number 043-01

Camp: 43

Unit ID: 1

Title: Castañer Project

Operating agency: BSC

Opened: 7 1942

Closed: 12 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 51

-

CPS Camp No. 43, Aibonito, Puerto RicoThe Community Center. The boxes being carried on the heads of the men are little caskets with the bodies of prematurely born triplets attended by Dr. PreheimDigital Image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansasca. 1943

CPS Camp No. 43, Aibonito, Puerto RicoThe Community Center. The boxes being carried on the heads of the men are little caskets with the bodies of prematurely born triplets attended by Dr. PreheimDigital Image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansasca. 1943 -

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoConstruction under way.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoConstruction under way.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved. -

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoDan Boehm's picture of most pf the medical staff or related (kitchen, housekeeping, etc.); on front end of hospital.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoDan Boehm's picture of most pf the medical staff or related (kitchen, housekeeping, etc.); on front end of hospital.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved. -

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoWilbur Holderread and assistant use oxen power for plowing.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoWilbur Holderread and assistant use oxen power for plowing.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved. -

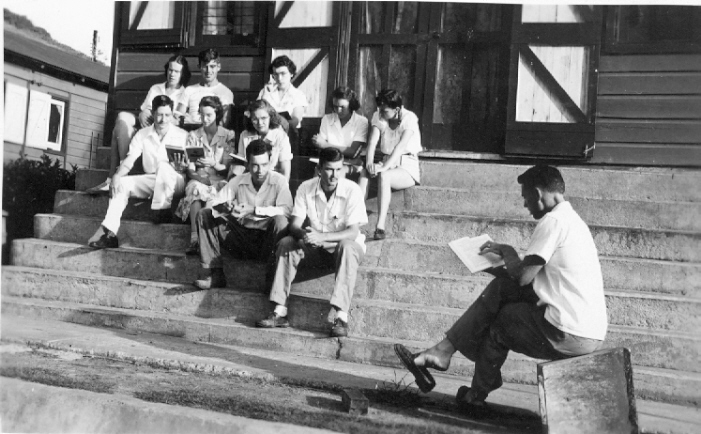

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoSpanish class.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoSpanish class.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved. -

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 4, St. Thomas Virgin IslandsBlackbeards CPS Unit Quarters. From the J. Henry Dasenbrock CollectionDigital Image Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 4, St. Thomas Virgin IslandsBlackbeards CPS Unit Quarters. From the J. Henry Dasenbrock CollectionDigital Image Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved -

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 2, Aibonito, Puerto RicoAibonito, Puerto Rico, camp 43.Box 1, Folder 24. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 2, Aibonito, Puerto RicoAibonito, Puerto Rico, camp 43.Box 1, Folder 24. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 2, Aibonito, Puerto RicoAibonito, Puerto Rico, camp 43. The inaugeration crowd at the front of the hospital for the official opening after the dedication address delivered by Dr. Hiebert in the community center.Box 1, Folder 24. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 2, Aibonito, Puerto RicoAibonito, Puerto Rico, camp 43. The inaugeration crowd at the front of the hospital for the official opening after the dedication address delivered by Dr. Hiebert in the community center.Box 1, Folder 24. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoLate August, 1943

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoLate August, 1943 -

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoPuerto Rico

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoPuerto Rico -

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoSan Just, Puerto Rico. Chris Ahrens looking at parts of privy constructionMay 29, 1945

CPS Camp No. 43, subunit 1, Castñer Puerto RicoSan Just, Puerto Rico. Chris Ahrens looking at parts of privy constructionMay 29, 1945

-

ca. 1943

ca. 1943 -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

May 29, 1945

May 29, 1945

CPS Camp No. 43 Subunit 1, located in Adjuntas, Puerto Rico, was operated by the Brethren Service Committee in cooperation with many local groups as well as with both island and U. S. government agencies that provided technical and other support. It opened in July 1942 and closed as a CPS unit in late 1946. The men constructed a small hospital, developed a community center and operated programs in both. The Brethren continued medical and social services after CPS ended.

Located in a thickly populated and mountainous area in the coffee growing west central part of the island, Castañer was chosen as the initial site because of its dire need for medical services. Lares, a town seventeen miles away had one seventy--year-old doctor, while Adjuntas, thirteen miles in the other direction had none. Thus some forty to fifty thousand people were served by one doctor and a nurse at Castañer.

The Castañer Project:

Since many men in CPS had expressed interest in relief work, the Brethren Service Committee explored work in Puerto Rico with the National Service Board, Selective Service and government agencies. On the poverty stricken island, many Puerto Ricans spent most of their income on food. Malnutrition, poor housing, and inadequate public services contributed to a high rate of tuberculosis, hookworm and other intestinal diseases. President Roosevelt set up the Puerto Rican Restoration Administration (PRRA) in 1935 to attack these problems.

PRRA had purchased large individually owned farms and subdivided them into units of one to five acres on which they built low cost, but hurricane resistant homes. They then sold them to farm laborers on a long term payment basis. These homesteads, located adjacent to a large central farm and a community center, provided much needed housing and access to work and services. Due to insufficient funds, the project cut back services in 1942.

The Martin J. Brumbaugh Reconstruction Unit addressed the community program of medical care, public health and social service. I was named for one of the state’s highly respected residents who had been president of Juniata College in Pennsylvania and professor at the University of Pennsylvania before being named in 1900 by President William McKinley as the first commissioner of education in Puerto Rico. This cooperative enterprise between PRRA and the Brethren Service Committee grew into collaborative effort including the Friends and Mennonites under Brethren overall administration.

The Brethren utilized an advisory committee composed of one Brethren, Friend and Mennonite to determine broad general policy, offer counsel, and advice. The committee also affirmed the appointment of the general director. The Church of the Brethren Elgin Office supervised administration of the program through the team of L. S. Brubaker, M. R. Zigler and W. Harold Row. “The CPS men who had been trained for service in China, but forbidden exit from the United States by law, were permitted to go to Puerto Rico.” (Kreider p. 26)

Four units developed, each project directed largely by its own local staff. The Brethren operated Castañer and St. Thomas, the Friends oversaw Zalduando, and the Mennonites LaPlata, each in cooperation with the Brethren on issues of overall relationships with PRRA and common work in the units. All worked effectively with each community as well as government agencies to introduce programs that sustained funding by the Insular government at the conclusion of CPS. The Brethren and Mennonites continued their relationship with the projects after CPS ended.

Directors: Dr. Daryl Parker, Rufus King, Herman Will, James Martin, Paul Leatherman

Eleven men constituted the original unit at Castañer. With gradual personnel additions, by the summer of 1943 the unit had grown to eighteen and by the following year to twenty-five men. Some were married.

Men in Brethren camps and units tended to report diverse religious affiliation when they entered CPS, although the Brethren projects usually included a core of men with Brethren denominational affiliation. Men in Brethren projects reported considerably more education and professional experience than those who enlisted in the Army and Navy, and brought an average of 12.22 years of education, thirty-nine percent of whom had completed one to three years of college, had graduated or completed some graduate education. Eighteen percent of men in Brethren camps and units entered CPS from technical and professional work. (Sibley and Jacob pp. 171-172)

The project placed its early emphasis on constructing a small hospital by remodeling an old barrack style structure. The renovation included installation of concrete piers for the foundation, leveling floors, interchanging wall sections, erecting partitions, overhauling the electrical and plumbing systems, constructing cabinets prior to painting the structure inside and out. The PRRA supplied the materials and the unit men completed the work.

The building included a large kitchen, dining room, operating room, obstetrics room, wards for men, women and children, doctor’s office and X-ray room. The facility also housed a diagnostic laboratory set up by one of the CPS men so the hospital could service the community and also other rural dispensaries. An ambulance sent from the United States made it possible to provide service to the area as well as to hospitals on both the north and south coasts.

As was the model in the PRRA, community centers provided schools, recreation and health services to the farmers and families living in homes clustered around the major fields. Within the first year of construction and operation, the doctors had performed nearly 200 operations, given 827 typhoid injections and 220 smallpox vaccinations; first aid classes were organized along with nurses’ training and training of local persons as nurses’ aides. The community center had also instituted a recreation program for indoor and outdoor games. (Eisan p. 337)

The community center program grew with the addition of a recreation program, courts and equipment. The unit organized a small public library with Spanish language books on loan from San Juan as well as a movie series. The center housed community meetings, and later supported clubs for boys and girls, crafts, classes in English, child care, and carpentry. Then summer camps for boys and girls began.

In the next year, the project added a medical dispensary in Rio Prieto several miles from Castañer. Each Saturday a hospital group delivered services (medical examinations, prescriptions, dental extractions) as well as provision for ambulance service, lab exams, hospitalization and surgery at Castañer as needed.

In addition to the CPS men, medical doctors, nurses, others with professional training, wives of unit members, and native Puerto Ricans staffed the project so that the total personnel numbered around sixty. This permitted the expansion of public health projects to include school and home visitations, health education, hookworm control and a tuberculosis survey. The hospital proved to be such a successful model for rural health care delivery that in 1945 the Insular Legislature approved $20,000 to be used towards its operation.

J. Kenneth Kreider reports that one of the CPS men, Caleb Frantz, who first worked as an orderly in the men’s ward, was later trained to assemble surgical instruments and supplies, and eventually learned to serve as an assistant in surgery and the delivery room because of the shortage of trained nurses. Frantz told Kreider this story of a memorable delivery.

. . . his task was to dispense drops of anesthesia for the mother-to-be on command from the physician, Dr. Everett B. Myers. The birth was imminent, so with the next contraction he asked the woman to push. She did, whereupon she also started choking and gagging in great distress. Frantz, suspecting vomit, grabbed an emesis basin. Just then, out of her mouth shot several inches of an adult ascaris worm, (an intestinal parasite, ascaris lumbricoides, thick as a pencil and often ten inches long). Not wanting to seek instructions from the doctor or nurse at a critical moment of delivery, Frantz looped his finger around the worm and “delivered” it from the woman’s throat. Her eyes opened wide in astonishment; such worms are normally eliminated in the other direction! Moments later, the healthy baby was born. When things settled down after the excitement and stress of delivery, Frantz showed Dr. Myers and the nurse the contents of the emesis basin, saying, “A minute before you delivered the baby, I delivered this”! Were they surprised? To say the least, that was a new twist on multiple births for everyone concerned. (J. Kenneth Kreider personal correspondence November 27, 2010)

Throughout the life of the unit, men performed construction and maintenance work on buildings, remodeled and repaired equipment, creatively using whatever materials were available.

When CPS ended, the Brethren continued to sponsor the program of medical and social services with an increased emphasis on religious ministry. In 1958, Nathan F. Leopold, Jr., infamous as half of the Leopold-Loeb murder of a young boy in Chicago in 1924, upon his parole and release from Stateville Prison in Illinois to the Brethren Executive Secretary W. Harold Row, operated the x-ray facility at the hospital. Row personally accompanied him to Castañer on March 15, 1958, after having secured permission from the people at the hospital and the governor of Puerto Rico. Of this unusual arrangement, Leopold later wrote:

So far as I am aware, mine was the first case in which the Brethren sponsored a man released from prison on parole. To me the Brethren Service Commission offered the job, the home, and the sponsorship without which a man cannot be paroled. But it gave me so much more than that—the companionship, the acceptance, the love which would have rendered a violation of parole almost impossible. A man would have had to work hard indeed to violate parole in such an environment. (in Kreider p. 28)

In 1976, the Brethren Service and Church of the Brethren, as had been the original plan, turned the hospital over to the local board of directors.

The men drew little distinction between “unit life” and “unit work” as communities of interest found expression in the service rendered. Almost all of the unit study related to the challenges faced at Castañer, and included courses in first aid, history and social problems of Puerto Rico, Spanish, public health and hospital procedures. Members studied Spanish individually throughout the duration of the unit.

In the early months, the members worshiped together in Sunday evening meetings. Later, members gathered for group worship in the mornings. Some took an interest in the local Puerto Rican services in Spanish.

According to Eisan, group loyalty usually overcame the frustrations of wartime transportation and communication, shortages of supplies and personnel to meet the needs of the people (p. 357).

The group experienced personal tragedy and sorrow in the death of three unit members—Elmer Hartzler, Elzie Ray Holderreed, and Isaac Harvey Horner. Hartzler drowned while swimming in May 1943, Holderreed died during his service, and Horner soon after returning to the mainland.

The Newsletter/Puerto Rico Newsletter, published in summer 1943 through January 1944, reported on activity of all the units included in the Castañer Project of the Brumbaugh Unit. The men published Castañer Newsletter from April 1944 through November 1945. The project and the newsletter continued on after CPS ended.

See J. Henry Dasenbrock, To the Beat of a Different Drummer. Winona, MN: Northland Press, 1989, pp 83-160.

For more information on Castañer and the other units working with the PRRA, see Leslie Eisan, Pathways of Peace: A History of the Civilian Public Service Program Administered by the Brethren Service Committee. Elgin, IL: Brethren Publishing House, 1948, Chapter 11, pp. 333-359.

For general information on the work and life in CPS camps and units, see Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. Intercourse, PA: Good Books 1990.

See also J. Kenneth Kreider, A Cup of Cold Water: The Story of Brethren Service. Elgin, IL: Brethren Press, 2001, pp. 26-32.

See also digital photo images of CPS and Voluntary Service work in Puerto Rico on the flikr website compiled by Tom Lehman at http://www.flickr.com/photos/tlehman Note the collections on Puerto Rico within the site: Puerto Rico, 1940s-1950s (81 sets, some by CPS workers); Old Puerto Rico Photos & Postcards (4 sets); Puerto Rico Black & White (1 set); Art Gallery (2 sets).

Nathan F. Leopold, Life Plus 99 Years. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1958.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952, pp. 141-143.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.