CPS Unit Number 148-01

Camp: 148

Unit ID: 1

Operating agency: SSS

Opened: 6 1945

Closed: 12 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 71

-

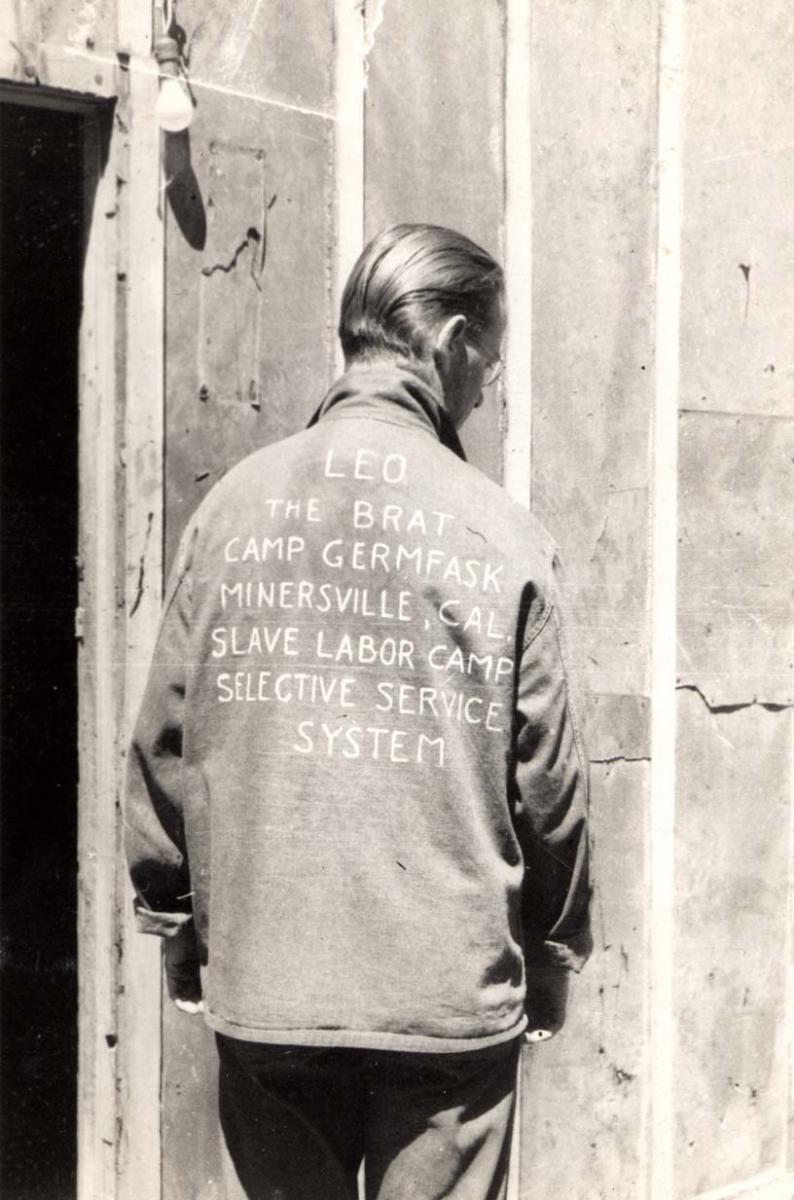

CPS Camp No. 148, Minersville, California"Leo the Brat"Digital image from the Bent Andresen Collected Papers (CDGA), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 148, Minersville, California"Leo the Brat"Digital image from the Bent Andresen Collected Papers (CDGA), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

This Forest Service Camp was located near Minersville in a very isolated area in the North Central Quadrant of California within the Shasta-Trinity National Forest. In 1959, Minersville, near California Route 3 and the Trinity River, was flooded when the Trinity Reservoir was built.

Director: Bliss Haynes

Minersville became the last stopping point for those men who had been in government camps and resisted work for one reason or another. They were transferred in from CPS Camp No. 135 in Germfask, Michigan when it closed.

Many of the men at Germfask had been transferred from government camps at Lapine, Oregon and Mancos, Colorado after having been identified as “non-cooperators, men chronically reporting to sick call, men with psychiatric ailments, agitators and general troublemakers”. (French to Hershey, May 21, 1943 in Sibley and Jacob p. 252-253)

Other men at Germfask had expressed their desire to work in government camps rather than in the religious based camps and units, fully committed to a philosophy of resisting war. They felt in this manner they could directly express their views to Selective Service.

Many of these men had entered CPS with not only college education, but also graduate education. Further, many entered CPS from technical and professional occupations and other positions of business and administrative leadership.

Men fought fires in fire season, and conducted fire prevention duties and along with maintenance of the camp, forest and trails in other seasons.

Selective Service approved the work for all CPS projects, camps and units as spelled out by Executive Order No. 8675 (6 F.R. 831), Feb. 6, 1941. The Director considered five factors to approve new projects.

1. Is the project important to the government in the emergency considering the manpower available, and is the project the most important thing that can be done at the time, and will it continue to be important with the probable changes in the situation?

2. Will the conscientious objector do it?

3. Will the public tolerate the objectors in the community where the project is located?

4. Will other employable labor be displaced?

5. Will it raise political controversy? (from the first report of the Director of Selective Service in 1942, in Sibley and Jacob p. 225)

In reality, the convenience of government agencies appeared to determine the selection of projects, rather than concern for the urgency of the task or its broader contribution to the larger concerns of the society. Federal, and later state agencies, received the projects; private institutions were generally dismissed when making proposals for CO assistance. Selective Service doled out projects based on prior cooperation, influenced by the pressures agencies exerted through legislative and administrative channels. These practices made it difficult to make the case that each of the projects met the definition for “work of national importance”.

In reality many agencies were reluctant at first to use CO men, but after they had proved their worth, they were in high demand. (Sibley and Jacob p. 225)

Colonel Kosch resisted innovative projects, preferring doing business with known agencies and extending existing projects. Many of the projects were located in highly secluded areas in an effort to avoid complaints of labor and other groups or community and political controversy.

Selective Service insisted that camps be “continuously manned”, even though the tasks were menial and unrelated to the wartime social emergencies. These conditions set the stage for struggle over the nature of “work of national importance” throughout CPS, and unmanageable work stoppages after cessation of hostilities.

The men at Minersville continued to challenge the authority of Selective Service. Twelve men were arrested and held for grand jury on charges of insubordination for refusing to tear down partitions around their bunks. After protracted legal and extralegal formalities, the charges were dropped.

A tough Forest Service project superintendent threatened fisticuffs with the COs after a protracted period of needling, but that proved an unsuccessful approach.

When work stoppage began, other camps and units across CPS united in protest against the government’s discriminatory treatment of COs. Men at Glendora went on strike April 24, 1946, to protest the transfer of two men to Minersville, characterized as “a punishment camp”. By May 15, the strikers at Glendora numbered eighty-seven; the CPS Strike Committee at CPS Camp No. 21 at Cascade Locks in Oregon sent out a letter asking for funds to support the strike. (Kovac pp. 148-149)

Frustrated assignees still held in the camps demanded prompt release since war hostilities had ended. By late 1946, a Gallup poll conducted in December revealed that sixty-nine percent of Americans favored releasing COs still in custody. (Goossen pp. 117-18)

“The lesson of government camps was not lost on the historic peace churches. When the 1948 conscription program was developed, one alternative they quickly rejected was governmental management of camps”. (Keim and Stoltzfus 1988 pp. 124-25)

Germfask Newsletter, continued, brought from CPS Camp No. 135 at Germfask, Michigan when it closed. The men continued to publish it through 1946.

The men published Minersville Fortnighly Nuggets beginning in July 1945.

See Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

See Albert M. Keim and Grant M. Stoltzfus, The Politics of Conscience: The Historic Peace Churches and America at War, 1917-1955. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1988.

See Jeffrey Kovac, Refusing War, Affirming Peace: A History of Civilian Public Service at Camp No. 21 at Cascade Locks. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 2009.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952, Chapter XI Government Camps: Prescriptions for “Troublemakers” pp. 242-256.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.