CPS Unit Number 014-01

Camp: 14

Unit ID: 1

Operating agency: AFSC

Opened: 6 1941

Closed: 4 1943

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 193

-

CPS Camp # 14, Merom, IndianaCamp SignDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp # 14, Merom, IndianaCamp SignDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp # 14, Merom, IndianaLoading trucksDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp # 14, Merom, IndianaLoading trucksDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

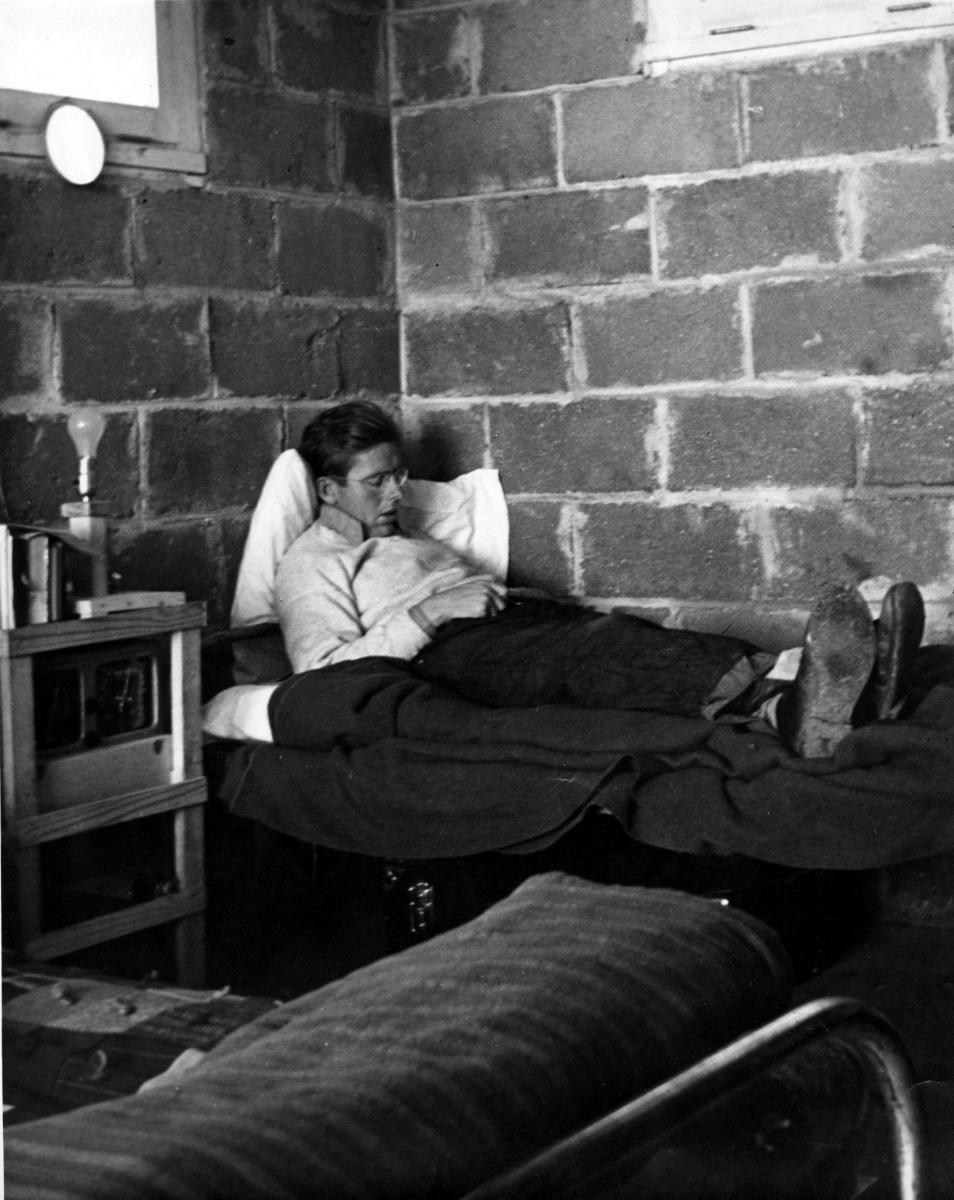

CPS Camp # 14, Merom, IndianaRest is Sweet After a Day 'On Project.'Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp # 14, Merom, IndianaRest is Sweet After a Day 'On Project.'Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 14College Hall in background, new dormitories in foreground. Merom, Indiana. November 1941. Photo by Reed Wilson.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 14College Hall in background, new dormitories in foreground. Merom, Indiana. November 1941. Photo by Reed Wilson.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 14Soil Conservation - soil grading. Five men and one tractor. Merom, Indiana.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 14Soil Conservation - soil grading. Five men and one tractor. Merom, Indiana.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 14, a Soil Conservation Service base camp, located in Merom, Indiana and operated by the American Friends Service Committee, opened in June 1941 and closed in April 1943. Men worked on irrigation projects to reclaim and develop farmland.

CPS Camp No. 14, a Soil Conservation Service base camp, located in Merom, Indiana, situated on a bluff high above the Wabash River, thirty-four miles south of Terra Haute, was on the grounds of the Merom Institute. The camp, operated by the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), opened in June 1941 and closed in April 1943, when the camp moved to Trenton, in northwestern North Dakota.

During the winter of 1941, AFSC accepted the invitation of the Merom Institute to locate a CPS camp on the campus. Originally the home of Union Christian College, a small co-educational liberal arts college that closed in 1924, the facilities reopened in 1936 as the Merom Institute, a religious extension service for rural Illinois, Indiana and Ohio. The four story brick building, College Hall, constructed in 1860, served as “the center of life at CPS Camp No. 14”.

“Standing in the cupola, ninety feet above the surface of the bluff on which the building rests, itself 200 feet above the Wabash River, we can see more than 300 square miles of Illinois and Indiana farmland and the smokestacks of half a dozen villages.” (The Plowshare, October 18, 1941 p. 5)

The Merom Institute and Conference Center has operated since 1984 under the auspices of the Indiana-Kentucky Conference of the United Church of Christ. http://www.ikcucc.org

Director: Ed Peacock, Tom Potts, Claude Shotts

Dietician: Helen Albert, Mrs. Byron Thomas

Nurse: Miriam Marolf, Beulah Oliphant

Secretary: Edith Morrissett

The one hundred and thirty-nine men listed on the June 20, 1942 roster entered from sixteen different states, with thirty each from Illinois and Indiana.

The men at American Friends Service Committee camps tended to constitute the most religiously diverse group of men, including those who reported no religious affiliation at entry into CPS. At Merom, sixty of the men had reported Friends affiliation and seven reported no affiliation. Seventy-two men reported affiliation with twenty other religious groups, including Christian Scientist, Swedish Covenant, Jehovah’s Witness, Islamic and Greek Orthodox.

They tended to report a variety of occupations, and numbers from cities were greater than from rural areas. The Merom men included teachers, students, farmers, a librarian, sales people, social workers, a welder, an electrician, a professional wrestler, musicians, a reporter, an architect, a lawyer, a radio dramatist, draftsmen, punch press operator, electrical engineer, electrical contractor, a publisher, and factory workers among others.

Men in the Friends camps on average had completed 14.27 years of education, including some with graduate as well as post graduate education. (Sibley and Jacob pp. 171-72)

The anniversary issue of The Plowshare described the “work of national importance” performed by Merom men, who worked for the Soil Conservation Service in Sullivan County on nine and a half hour day shifts. (June 1942 p. 11)

In the first year of the camp, they completed seven stock water ponds and tanks to hold rainfall in clean storage for livestock and as a refuge for wildlife. Four additional ponds and tanks were near completion.

In the same period, they constructed over 2,130 rods of fence to control livestock by confining them to pastured areas, or prohibiting them from areas where they might contribute to soil erosion by their “grazing, rooting and trampling”.

In cooperation with farmers, the men, using tractors and graders, built six miles of terraces on the land to carry excess water into a protected outlet leading down the hill.

“Merom campers have planted 57,200 trees on steep, severely eroded land; on areas around farm ponds for erosion control, wildlife refuge, and shade; and as windbreaks to hold soil in place.” (Plowshares June 1942 p. 11)

The men also constructed 2,200 feet of diversion ditch, 7,800 feet of outlet channel while also planting, seeding and sodding 7,500 yards of channel. They sloped banks, cleared channels and levees, and cut out worthless material in farm woodland.

Five CPS men serving as an engineering crew “completed all the farm and public drainage ditch surveying and drafting work for the camp, and performed some drafting for two CCC camps in adjoining counties”. The report clerk, who also served as camp mathematician, computed run-off data for an SCS experiment station in Ohio. Another tested soils. Two men issued, stored and cared for all SCS tools and two mechanics kept trucks in good operating condition. “Another crew built the SCS repair garage and the truck shelter”.

The camp opened to some protests from townspeople certain that the men would take away work from employees of the Work Progress Administration. According to Goossen, some angry members of the American Legion threatened to run the COs out of town. (p. 39)

Merom men, organized by Sam Bertsche, a graduate of Union Theological Seminary with a masters degree in music, sang in a choir, three quartets, and as soloists for area churches and groups. Arthur Chance served as president of the choir which rehearsed twice weekly with a special rehearsal just before a concert. William Rhodes, business manager, scheduled appearances for regular performances by the various groups in the surrounding communities and beyond. The men also arranged for radio time for the choir.

A drama group directed by Stuart Olbrich wrote and performed their work at the camp and in the community. They planned to write a peace play.

The men built a darkroom for photographers in College Hall.

Campers interested in mechanics, under the supervision of Robert Starbuck an electrical contractor before entering CPS, built portable light equipment to use in illuminating picnic grounds at night, and planned to build a gasoline scooter. Starbuck and Philip Galliers, an industrial designer, worked with the group, designing plans for an electric refrigerator.

One camper served as a regular organist for the Methodist church in Sullivan. John Riebel and Dennis Wilcher, both entering from Y.M.C.A. work, “started a club for boys 12-15, for which 25 Merom boys turned out to play football and basketball on Saturdays”. (The Plowshare November 24, 1941 p. 3)

The Agriculture Committee assisted in work on the camp’s subsistence farm, preparing a chicken coop for 300 laying hens, supervising the harvest of potatoes, fruits and vegetables.

In September 1941 two seminars and four language classes met weekly. One on non-violent techniques focused on A.J. Muste’s “Non-Violence in an Aggressive World”. Another on Philosophy and Religion emphasized ethics and held sessions on Mysticism, Deeds and Words in Religion, Art of Morality, Church and State, each presented by one of the campers.

The education program focused on three fields—manual skills, soil conservation work, and the philosophy of pacifism.

With excellent athletic facilities at the camp, the recreation program included volleyball, tennis matches, football, basketball, table tennis, box hockey, shuffle board and paddle soccer, croquet and horseshoes, and swimming “in a nearby gravel pit”.

Four of the men came down with typhoid, all working on the same crew. That caused the Indiana State Board of Health to do a thorough exploration of conditions at the farm where they worked. The recommendations of the camp physician and the Board of Health, after they found no definitive cause, was that all men working with soil needed to wash with an antiseptic and use paper towels at the conclusion of their work and before eating. The men were also urged to drink no water other than the water at the camp, which was chlorinated and tested regularly. (The Plowshare September-October, 1942 p. 9)

The same issue of The Plowshare reported that one man, Norman Cardin volunteered for one of the “human guinea pig projects” at Welfare Island Hospital in New York. Without fully realizing the nature of the project in altitude studies related to diet, he chose to withdraw after a few days and returned to camp. (p. 9)

The men published Vol. 1, no. 1 of a camp paper Pacifist Study Exchange in March 1942, designed not only for Merom, but also to be shared with other camps “to help in its study of the pacifist road to power”. The initial group of camps included San Dimas in California, Magnolia in Arkansas, Royalston and Ashburnham in Massachusetts, Stronach in Michigan, Denison in Iowa, Buck Creek in North Carolina and Henry, Illinois. It included theme topics for study and a bibliography. Tom Steger, an artist entering from Detroit, served as editor and Crane Rosenbaum, a reporter from Ames, Iowa as associate editor. The first issue was published in Detroit.

The men published The Plowshare “ten to twelve times yearly”, and it continued as The Irrigator when the camp moved to Trenton, North Dakota as CPS Camp No. 94.

The Swarthmore College Peace Collection contains one issue of Iowa Peace News Vol. 1 No. 7 from Merom dated December 13, 1941.

For stories from men who, as COs, walked to a different drummer during World War II, see Mary R. Hopkins, Editor, Men of Peace: World War II Conscientious Objectors. Caye Caulker, Belize: Producciones de le Hamaca, 2010, Neil H. Hartman, 99. 178-184; T. Canby Jones, pp. 96-110.

For general information on CPS camps and units, see Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. Intercourse, PA: Good Books 1990.

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

The Pacifist Study Exchange, Vol. 1 No. 1 (March 1942) in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Section 3, Box 4.

The Plowshare, Vol. 1 No. 2 (September 15, 1941); Vol. 1 No. 3 (October 18, 1941); Vol. 1 No. 4 (November 24, 1941); Vol. 1 No. 11 (June 26, 1941); Vol. 2 No. 1 (August 1942); Issue 14, (September-October 1942); Issue 17, (January-February 1943); Issue 18 (March 1943) in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Section 3, Box 4.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector 1940-1947. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.