CPS Unit Number 135-01

Camp: 135

Unit ID: 1

Title: Seney Wildlife Refuge

Operating agency: SSS

Opened: 5 1944

Closed: 6 1945

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 102

-

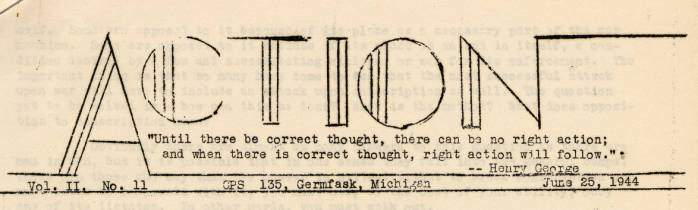

CPS Camp No. 135Action was a newsletter published by the men at Camp 135 in June 1944.Digital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 135Action was a newsletter published by the men at Camp 135 in June 1944.Digital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

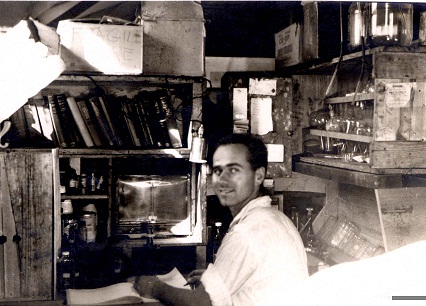

CPS Camp No. 135Dr. Don DeVault in his homemade laboratory, CPS Camp #135, 10/27/44.Digital image from the Paul Wilhelm & Jayne Tuttle Wilhelm Collected Papers (CDG-A), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 135Dr. Don DeVault in his homemade laboratory, CPS Camp #135, 10/27/44.Digital image from the Paul Wilhelm & Jayne Tuttle Wilhelm Collected Papers (CDG-A), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 135, a Fish and Wildlife camp near Germfask, Michigan operated by Selective Service, opened in May 1944 and closed in June 1945. Some men elected government-run camps after becoming disillusioned with religiously-based camps. The men moved dirt, controlled weeds and dug duck ponds as part of the development of the game preserve.

The CPS unit at Germfask, Michigan, a Fish and Wildlife camp operated by the Selective Service opened in June 1945. The third of the government operated camps, Germfask became a place of last resort for CPS men who had demonstrated a pattern of disrupting programs at other CPS camps and units.

Located in the isolated east-central Upper Peninsula of Michigan, the small village of Germfask is on Michigan Highway 77 and the Manistique River. Early in the town history, lumberman dumped logs into the river to float them down to mills in Manistique on Lake Michigan. The Seney Wildlife Refuge was located three miles north of Germfask.

Director: Norman V. Nelson

Many of the men had been transferred from government camps at Lapine and Mancos after having been identified as “non-cooperators, men chronically reporting to sick call, men with psychiatric ailments, agitators and general troublemakers”. (French to Hershey, May 21, 1943 in Sibley and Jacob p. 252-253)

Other men at the camp had expressed their desire to work in government camps rather than in the religiously based camps and units, fully committed to a philosophy of resisting war, and able to directly express their views to Selective Service.

The camp included men who entered CPS with not only college education, but also graduate education, as well as those who when entering came from technical and professional occupations.

Men in the camp moved dirt and controlled weeds on the refuge, established to protect birds and other wildlife, as well as the wetland, grassland and forest habitat. The work included digging duck ponds as part of the development of the game preserve.

While many of the COs transferred to the camp expecting harsh treatment, they found instead lenient supervisors, few work requirements, and minimal reinforcement of regulations.

While CPS leaders, when supporting the creation of government run camps, called for the men to be paid for their service, Selective Service did not change its regulations. As was the case in all camps and units, men served without pay for their work, but received a small allowance each month to cover incidental expenses.

Selective Service considered the issues of concern to CPS men before opening the government camps. They intentionally offered a larger food budget and attempted to provide constructive work that would better utilize men’s skills. Selective Service did not meet the top concern of CPS men that they be paid for their work.

The men at first found the liberal interpretation of regulations at Germfask surprising, as the camp administration and work supervisors tended to ignore individualistic disregard of regulation.

One visitor sympathetic to the COs reported that he was stunned to find “washrooms the filthiest anywhere, dining habits those of hogs, 75% of the men unshaven, unkempt and dirty, liquor being drunk in the dorms on Sunday morning at church time, almost no project work done.” (in Sibley and Jacob p. 253)

Controversy arose in fall 1944 over one of the men, Don Charles DeVault, a Ph.D. in chemistry assigned to Germfask. He had claimed IV-E status in 1941 and received temporary deferment to teach and continue his research at Stanford University, but was then reclassified to I-A-O status in 1942. He refused induction into the army in January 1943 and was sentenced to prison in March until paroled in December to Mancos, Colorado CPS Camp No. 111 also operated by Selective Service. There, on their own time, he and another CO, Forrest Leever, began experimenting with chemicals to develop antibiotics. During May through July, DeVault appealed to his parole officer to be transferred to a research university. His appeal denied, he was transferred to Germfask on July 27 and continued his work on his own time. In September he wrote to General Hershey requesting an assignment doing chemical research. His request was denied in a letter from Colonel Lewis Kosch, who stated that he would be considered for guinea pig research. The camp publication Germfask Newsletter described the next set of events.

Sept. 27: DeVault tells Director Nelson: “This reply means that I am done with this foolishness. Henceforth I shall be reporting for work on penicillin or related subjects.” Remains in camp in his chosen work.

Oct. 17: Submits detailed report to Director Nelson of the scientific work he has completed.

Oct. 27: Arrest blocks DeVault’s work.

When two COs tried to call newspapers to report the incident, they were told by the telephone operator that Director Norman V. Nelson had asked her to stop all long distance calls from the camp, and that she would need to secure his permission. When she called the camp, one of the COs answered the call and granted permission. They reached the Chicago Tribune. The next day, Director Nelson announced that all COs would be confined to camp and that no long distance calls could be made from the camp phone.

One of the papers published in the Upper Peninsula summarized the story.

Since September 27, DeVault has contended he should not waste his scientific skill in building duck ponds for the Fish and Wildlife Service . . . . Each morning when the trucks take the other men out to their pick and shovel work, he has remained in camp to carry on research with penicillin in the crude laboratory he has constructed in his barracks.

Author of ten research papers in the field of physical chemistry and holder of a Ph.D. degree, the young scientist stated before his arrest: “My case is no different from that of several thousand professional trained men confined by Selective Service in labor camps when they are anxious to use their training in a way which benefits humanity.” Conchies at Germfask say DeVault’s case brings to a head the high-handed way in which Selective Service has wasted their skills at ditch-digging jobs. (Escanaba Daily Press, 31 October, 1944 in Taylor p. 123)

A Washington Post editorial subsequently questioned why the talents and abilities of the men were not used more effectively in CPS.

DeVault was arrested and announced that he would plead no contest at his trial. He left CPS October 27, 1944. After the war, he conducted research and published in the areas of laser technology, biophysics and mechanical tunneling.

In a later incident, some neighbors became irate after a series of local vandalism incidents, and brought pressure on the camp director to declare nearby villages off limits. The press picked up the story in the Detroit Times. Time Magazine (February 19, 1945) covered the incident.

Selective Service officials were at their wits end last week. The problem that vexed them: how to deal with a group of draft-age Americans who have refused to fight, who now decline to work, and spend most of their waking hours finding new and more ostentatious ways of thumbing their noses at authority.

While the men agreed with the basic complaints reported, they found the reports inaccurate and inflammatory, distorting facts and exaggerating the number of men involved in the incidents. Colonel Kosch ordered the men restricted from visiting the village of Germfask.

The publicity caused the director to seek an immediate investigation from the F.B.I. and Lieutenant Colonel Simon P. Dunkel of Selective Service headquarters visited the camp. However, little could be done without a new law. Congressman Bradley drafted a law, but was not able to get it out of committee.

Selective Service attempted prosecution of the worst offenders but prosecutors did not want to crowd their dockets with CO disciplinary cases. They also sent files back to draft boards for reconsideration, but the war ended before COs had exhausted their rights of appeal.

The responses united the men to condemn camp officials for creating a false impression of the situation based on the behavior of only five or six individuals rather than supporting the camp administration’s “enlightened outlook” toward the Germfask men.

Resistance increased. A newly appointed camp manager, an ex-serviceman resigned within a few weeks of his appointment, convinced that the treatment of the COs at Germfask amounted to “re-establishment of slavery”. Sporadic shows of “firmness” continued until the men were discharged, and the camp closed, the remaining men transferred to Minersville in California.

The men published a camp paper Action in June 1944. A camp paper with the same title was published at CPS Camp No. 32 in West Campton, New Hampshire and at CPS Camp No. 111 at Mancos, Colorado.

They also published Germfask G.I., which changed its name to Germfask Newsletter for issue two, from May 1944 through April 1946. This newsletter continued when some of the men were transferred to CPS Camp No. 148 at Minersville, California.

Keim and Stolzfus, in writing about the government camps and the occupants as “the least cooperative, most politically conscious campers”, observed that the camps “. . . became a setting for those whose philosophy of conscientious objection gave high credence to resistance to war. . . . Those who lacked sympathy for the Civilian Public Service now had a way to put their convictions to work against Selective Service.” (p. 124)

Selective Service’s primary focus was not on “work of national importance”, but rather that the men yielded to government authority and obeyed orders. Those in government camps, both CPS men and camp administration, lived through frustrating times.

The compromises with government required to forge CPS in a time of national crisis, did not always satisfy many of the men the program sought to protect. The American Friends Service Committee withdrew from the program in March 1946, frustrated with the punitive aspects of the program and the struggles and objections of men in their camps and units. One Mennonite CO who had served three years in CPS observed,

Why not say—this was the best thing that could be worked out on short notice, with a government having no experience with alternate service and afraid to move, and worked out within the framework of adverse public opinion. In trying to improve it we have run up against the wall of government conservatism and lack of interest. Then when we have said this, we should say it again. (Paul Albrecht to Albert Gaeddert, 23 January, 1946 in Gaeddert Papers, Mennonite Library and Archives and quoted in Goossen p. 27-28)

See Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

See Albert N. Keim and Grant M. Stoltzfus, The Politics of Conscience: The Historic Peace Churches and America at War, 1917-1955. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1988.

See Mitchell Lee Robinson, “Civilian Public Service during World War II: The Dilemmas of Conscience and Conscription in a Free Society”. Ph.D. dissertation, Cornell University, 1990.

See Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952, Chapter XI, Government Camps, pp. 242-256.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.

See also Steven J. Taylor, Acts of Conscience: World War II, Mental Institutions, and Religious Objectors. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2009, Chapter 6 A Working Compromise Between Church and State.