CPS Unit Number 134-01

Camp: 134

Unit ID: 1

Operating agency: BSC

Opened: 5 1944

Closed: 5 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 306

-

CPS Camp No. 134The Nugget was a newsletter published by the men in Camp 134 in 1944 and 1945.Digital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 134The Nugget was a newsletter published by the men in Camp 134 in 1944 and 1945.Digital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

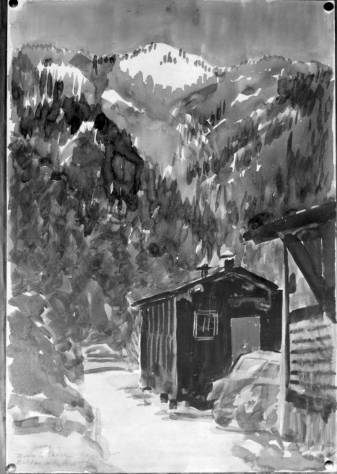

CPS Camp No. 134Painting of a mountain cabin by Waldo S. Chase titled "Belden"Lewis and Clark Digital Collection, Special Collections, Henry and Mary Blocher Collection1945

CPS Camp No. 134Painting of a mountain cabin by Waldo S. Chase titled "Belden"Lewis and Clark Digital Collection, Special Collections, Henry and Mary Blocher Collection1945 -

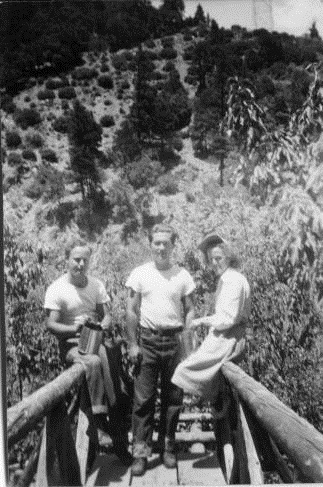

CPS Camp No. 134Dan Force, William and Dorothy Stafford picking berries near Camp 134.Lewis and Clark Digital Collection, Stafford Archives1944

CPS Camp No. 134Dan Force, William and Dorothy Stafford picking berries near Camp 134.Lewis and Clark Digital Collection, Stafford Archives1944

-

-

1945

1945 -

1944

1944

CPS Camp No. 134, a Forest Service base camp near Belden, California operated by the Brethren Service Committee, opened in May 1944 when the Santa Barbara CPS Camp No. 36 closed. The Belden camp continued until May 1946. Men fought fires, maintained and repaired equipment and performed fire prevention duties.

The camp was located near Belden on state highway 70, in Plumas County in the northeastern part of California. The Plumas Forest, heavily timbered, is a part of the northern Sierra Nevada Range and lies south of the Cascade Range.

Directors: D. C. Gnagy, O. P. Williams, D. K. Christenberry

Men in Brethren camps and units tended to report diverse religious affiliation when they entered CPS, although the Brethren projects usually included a core of those with Brethren affiliation.

Men in Brethren projects reported considerably more education and professional experience than those who enlisted in the Army and Navy, and brought an average of 12.22 years of education. Thirty-nine percent of the men had completed some college, had graduated, or done postgraduate work. (Sibley and Jacob p. 171)

Men in both Mennonite and Brethren camps reported from more rural areas at time of entering CPS than did men from Friends camps. Twenty-nine percent of men in Brethren camps reported their occupation as farming or other agricultural work upon entering CPS; eighteen percent reported technical and professional occupations; and sixteen percent business management, sales and public administration occupations when entering CPS. Another twenty-one percent reported skilled and semi-skilled trades. (Sibley and Jacob p. 172)

As their most significant duty, men fought fires. The west coast dry summers created high need for this assistance. Men on the “first action” fire crew worked near the pumper truck performing duties related to fire prevention and management or preparation of equipment. When a fire call came, they could be on the truck in two to three minutes. William Stafford, one of the COs who served at both Santa Barbara and Belden and later named the Poet Laureate of Oregon, gives the following account of a fire in the lava country of northern California.

The things we have seen on fires! They were the big adventures . . .of West Coast CPS. We tore along the highway, the wind buffeting us while we peeled oranges and squirmed down among the duffel bags for shelter.

Twenty miles from camp we turned into the sawmill road and picked up the rest of our men—about fifteen of them, where they had been piling brush all day. . . . We all transferred to the big crew truck, with plank benches across the back, all open to the scenery. We distributed to the brush crew the overcoats we had brought them from the camp, and some put the coats on at once, for we were going to cross high country, and even in the late afternoon the air from the snow near the road gets bitter.

[When the crew arrived] we set up tables, and a generator and light circuit, and a telephone. Then we began the institution of feeding—a tremendous institution on a fire.

Night closed in on us as we ate—steak, potatoes, peas, tomatoes, lettuce, bread, butter, jam, raspberries, oranges, coffee, and a second helping all around. . . .After supper we each took five blankets from the supply truck and hunted for a smooth place on the ground.

[The next morning] each man was issued a backpack pump, weighing about forty pounds or so, and a shovel or an axe. Five CO’s were issued to each Forest Service man; and to the grumbling accompaniment of sounds the cooks were making in protest of their dishwashing, we filed into the brush. . . . Volcanic dust swirled about our boots, and we began to climb a jagged lava slope, in an area sparsely overgrown with brush and some big pines. We began to build a “fire line,” or cleared space, downhill, about fifty feet from the fire which was still just a ground blaze and quiet from the night coolness and humidity. We built about three fourths of a mile of line, working farther and farther from the fire as the day’s heat allowed the flames to rise; and then we backfired into the burn. It was a beautiful sight. I could look up now and then and see, framed through a tangle of boughs, a chopper, his arms raised, his axe swinging; or a tired packer, the curve of his back a picture of weariness, bringing in water. Along part of our line the cover was fir, incense cedar, and ponderosa pine, with underbrush of nutmeg and madrone.

Our line held. By noon we were patrolling, now and then attacking spot fires that sprang up from sparks alighting beyond the lines; and as the midday wind came up we sometimes had the breathtaking experience of seeing the fire crown in places within the burn and go roaring like a waterfall, and spreading at runaway speed through the tops of snags and live fir and pine.

After noon we were sent to a new section of the fire, leaving a few men to patrol where we had been. Our task was to dig and chop out any hot tree, and to feel with our bare hands amidst the duff of the forest floor to find hot places; for the fire would eat along under the surface of the punky needles and bark. Whenever we uncovered a hot place, we squirted water on it from our heavy backpacks. Every half-hour or so we had to hike back to the pumper truck to get a refill.

By mid afternoon the fire was under control. We cleared off a place and sat down for sandwiches one of the packers had brought. Then we got up and patrolled, sighting along the ground for the tiniest smokes; for the afternoon wind would be dangerous. When the wind increased, about four, it raised three smokes in our area. We put them out. (William E. Stafford, Down in My Heart, p. 54 ff. in Eisan pp. 78-80)

When not fighting fires, men maintained a series of fire lookout towers, built roads and trail into back country, felled hundreds of dead trees called “snags”, and cleared brush. Others cleaned and maintained equipment and loaded trucks. In addition they performed maintenance and construction on buildings, cared for seedlings in Forest Service nurseries or surveyed trees estimating their diameter and the number of logs they would yield.

The Brethren camp staff worked with the men to organize the education, recreation, religious life and other leisure activities of the camp. A camp council and committees for each of the areas of camp life looked after specific concerns, but matters involving the men came to the camp meeting for discussion and action. Often assignees served on the staff, and from 1944 on, men also participated in selecting the camp director.

Many men participated in camp classes, while others pursued their own interests and course of study, relying on the camp library. The Belden library held 1,736 books and periodicals. The camp also offered a speaker and film program.

The men published a newspaper called The Nugget beginning in 1944 and continuing into 1945.

For information on Brethren forest service base camps and camp life see Leslie Eisan, Pathways of Peace: A History of the Civilian Public Service Program Administered by the Brethren Service Committee. Elgin, IL: Brethren Publishing House, 1948, Chapter 3 Base Camps: The Work Projects and the Camp Organization pp. 73-111; Chapter 4 Base Camps: Camp Life pp. 112-187.

For general information on the work and life in CPS camps and units, see Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. Intercourse, PA: Good Books 1990.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

William E. Stafford, Down in My Heart. Elgin, IL: Brethren Publishing House, 1947.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.