CPS Unit Number 129-01

Camp: 129

Unit ID: 1

Title: Pennhurst

Operating agency: AFSC

Opened: 1 1944

Closed: 8 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 34

-

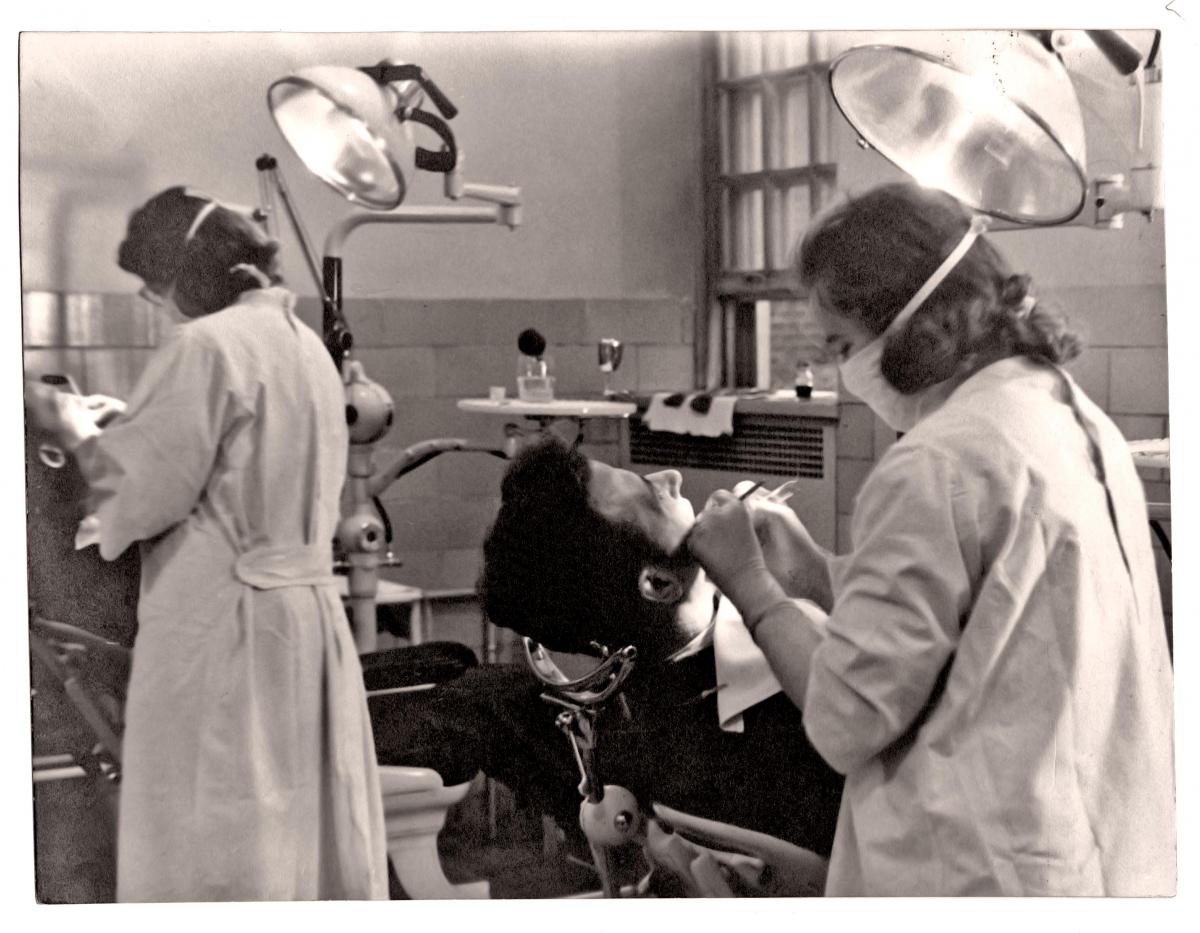

CPS Camp No. 129Barton [Baiton?] Alexander, CPS wife-Pennhurst. CPS wife at Pennhurst in dental clinic, operating[?]on patientDigital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945

CPS Camp No. 129Barton [Baiton?] Alexander, CPS wife-Pennhurst. CPS wife at Pennhurst in dental clinic, operating[?]on patientDigital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945

-

1945

1945

CPS Unit No. 129, a Training School unit at Pennhurst State Training School located in Spring City, Pennsylvania and operated by the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), opened in February 1944. When AFSC withdrew from the CPS program in March 1946, Selective Service operated the unit until it closed in August 1946. The men served as attendants in the wards.

Directors: Robert Beach, Wesley Shike, William Kelsch

Some of the men in the unit were married.

On average, men in Friends camps and units had completed 14.27 years of education, with sixty-eight percent reporting completion of some college, college graduation, or post graduate work. Forty-three percent of the men reported their occupation on entry to CPS as technical or professional work. (Sibley and Jacob pp. 171-72)

Men in Friends camps and units tended to report the greatest diversity in religious affiliation when entering CPS. In addition, a number of men reported no religious affiliation.

The chief difference between mental health units and training schools lay in the type of patient admitted. Training schools were devoted to care of those whose mental conditions derived from hereditary factors, or for whom there was little or no hope for cure. The work in training schools was very similar to that in mental hospitals.

Pennhurst Training School struggled to care for its caseload of twenty-five hundred patients. Fifteen hundred more waited for admission. Most of the unit members served as ward attendants. Wives also worked at the school.

Regular employees received low wages as the states underfunded mental hospitals and training schools.

On a visit to the school in 1945, Len Edelstein of the CPS Mental Hygiene Program described conditions.

At Pennhurst I found conditions rather similar to those at Byberry—namely lovely grounds, nice “façade”, but very old wooden buildings, dimly lighted and often pervaded with strong odors. The boys, crammed into day rooms—fed poor looking food on metal trays, are often worked 12 hours per day, 7 days a week—if they have sufficient brawn or mental ability. (in Taylor, p. 266)

During the period when CPS men and women collected narratives on treatment and abuse in mental hospitals, they included data from training schools as well. That information was published in Out of Sight, Out of Mind, later shown to reporters who exposed conditions in mental hospitals and training schools. The men and women COs at Pennhurst supplied information on conditions.

Unit men lived off the grounds because the school had no room or facilities to house them. Married men in this case could live with their wives.

When Selective Service issued Directive No. 4, which restricted men from living away from a camp or unit more than three nights a week, they tried to apply it uniformly across all the camps and units. Across the camps, a number of COs had organized a CPS Union, a major goal of which was to secure pay for work. The Union strongly opposed Directive No. 4, not only the living restriction, but also it restricted men from employment in off-duty hours to earn needed money to support their dependents.

Unit members published a camp paper Penn Points from November 1944 through October 1945 and The Notebook from January through December 1945.

Anthony Leeds, one of the COs at Pennhurst later described his experience:

I went for a miserable 20 months to a concentration camp called Pennhurst State Training School for Mental Defectives . . . . The patients most likely to get training and get better and go into a real world of work, somehow were found to have “broken a rule” so they were sent to U-Cottage, a slave house where they were beaten, had arms tied to steam pipes, and made to provide all the major labor of the institution. The Director, an alcoholic, and the Comptroller were in cahoots, many of the charge attendants in the cottages were drunks and even more of the assistant attendants were “rum-bums”. (in Taylor p. 266)

Channing B. Richardson, a CO at Pennhurst discharged from the unit in 1945, shortly thereafter published an article “A Hundred Thousand Defectives” in The Christian Century. It opened confronting faulty beliefs about “feeblemindedness and heredity”.

When one learns that approximately 80 percent of our defectives inherited their luck, one gets a glimpse of a huge future problem. The immediate background of the present problem is familiar to social workers—poverty, low home and family standards, delinquency, ignorance and sickness. A drag on his schoolmates, a joke for the cruel and a threat to his community, the defective committed to a state institution by a court or agency receives little better than custodial care to the end of his days.

Richardson went on to describe an ideal type of environment where such patients would be “secure against dangers, protected from illness and guarded against reproducing his kind” and provided psychometric testing, recreation and work programs. He also detailed barriers preventing realization of the idea, including institutional problems:

A catalogue of specific blockages on the road to reform would include interdepartmental rivalry, favoritism, boondoggling, buck-passing, incompetence, fear of supervisors and the future, lack of knowledge and pride in the work, shortsightedness and concern with appearances. (Richardson in Taylor p. 268)

Later Richardson became a professor at Hamilton College and acted as a counselor for COs during the Vietnam War. (Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Expressions of Quaker Conscientious Objection, CDGA)

Over two decades would pass before The American Association on Mental Deficiency addressed the problems of institutional abuses, overcrowding and understaffing in the 1970s.

One man, in a 1988 survey, reflected on his visit to Pennhurst some years later and recalled,

I visited Pennhurst Training School in 1975—some 30 years after leaving this institution. I found it nearly unrecognizable. It was now patient-oriented to an extent that was unbelievable from that which had prevailed in the war era. . . . I like to think that the presence of our CPS unit at that time must have played some role in achieving this transformation. (in Sareyan p. 253)

Though the institution had undergone some changes, in the late 1970s and early 1980s Pennhurst faced a major class-action lawsuit, Halderman v. Pennhurst State School and Hospital. In that period, it also defended a U. S. Supreme Court case, Romeo v. Youngberg, involving abuses and injuries to a Pennhurst resident Nicholas Romeo. The State of Pennsylvania ultimately closed the school in 1988. (Taylor p. 266) Judge Raymond Broderick, found that the institution approaches were inconsistent with the principle of normalization.

Since the early 1960’s there has been a distinct humanistic renaissance, replete with the acceptance of the theory of normalization for the [re]habilitation of the retarded. . . . The basic tenet of normalization is that a person responds according to the way he or she is treated. . . . The environment at Pennhurst is not conducive to normalization. (Taylor p. 378)

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

See Channing B. Richardson, “A Hundred Thousand Defectives,” Christian Century, January 23, 1946.

See also, Channing Bullfinch Richardson, in Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Expressions of Quaker Conscientious Objection (CDGA056). http://www.swarthmore.edu/library/peace/manuscriptcollections/quaker.co.expressions.htl

See Alex Sareyan, The Turning Point: How Persons of Conscience Brought About Major Change in the Care of America’s Mentally Ill. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1994.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.

For more in depth treatment of mental health and training school units, see Steven J. Taylor, Acts of Conscience: World War II, Mental Institutions, and Religious Objectors. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2009.