CPS Unit Number 115-17

Camp: 115

Unit ID: 17

Title: Universityof Minnesota: Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene

Operating agency: OSRD

Opened: 10 1943

Closed: 10 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 75

-

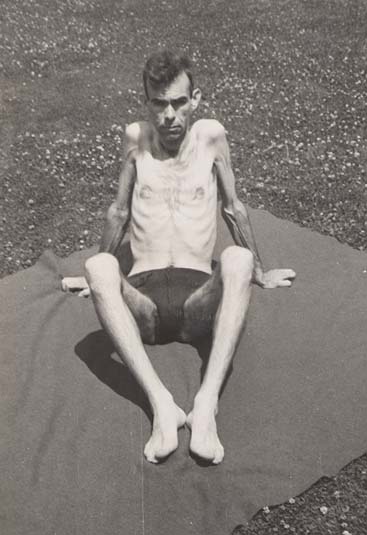

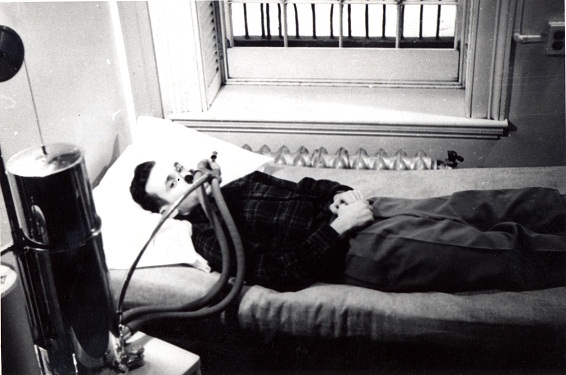

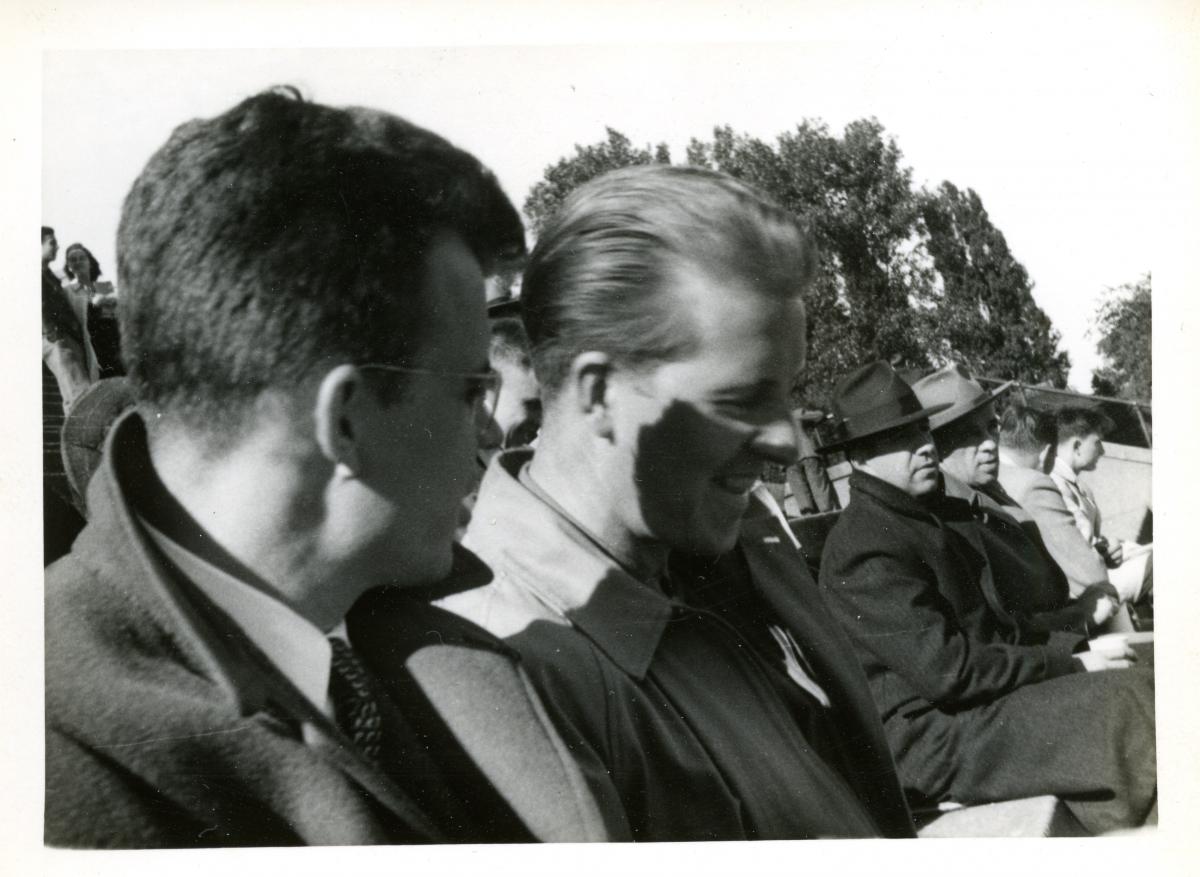

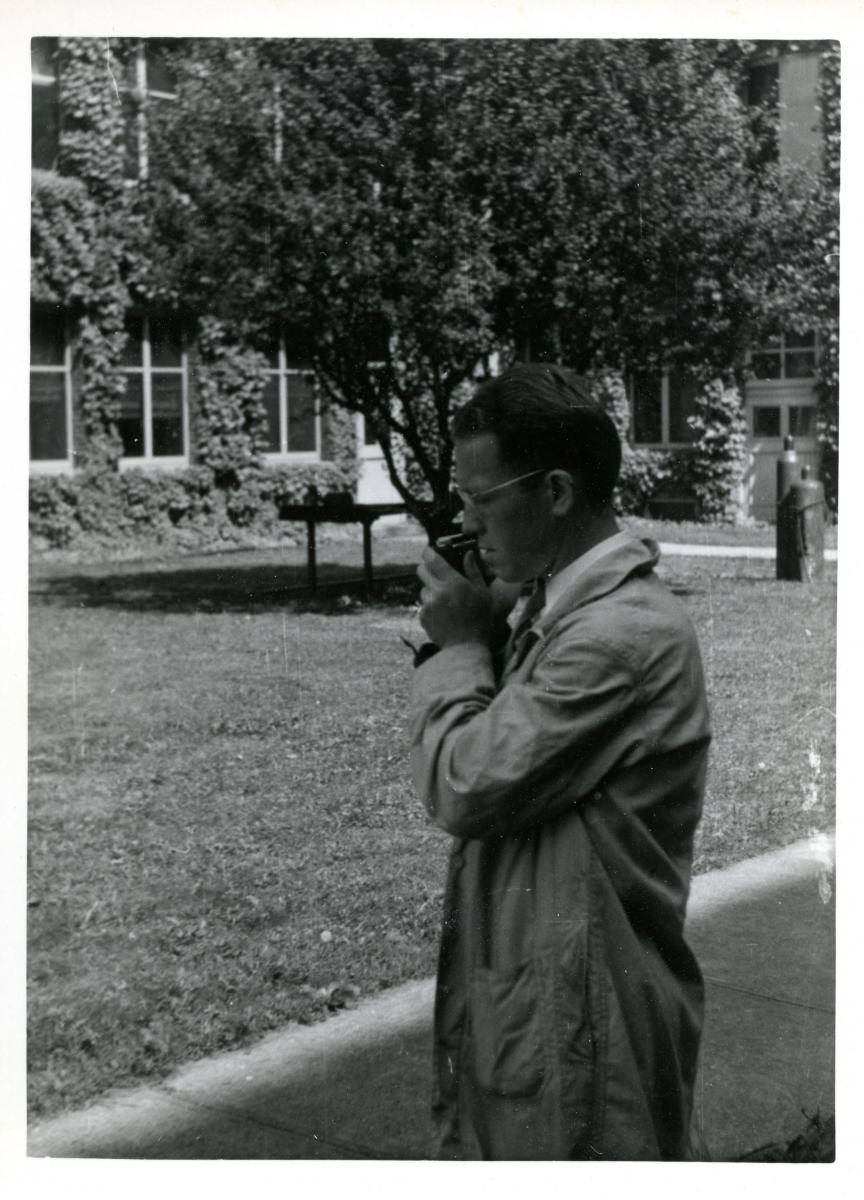

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 17Harold Blickenstaff. University of Minnesota Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene, Minneapolis, Minnesota.Digital image from the C.D. Smith Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Miscellaneous Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 17Harold Blickenstaff. University of Minnesota Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene, Minneapolis, Minnesota.Digital image from the C.D. Smith Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Miscellaneous Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

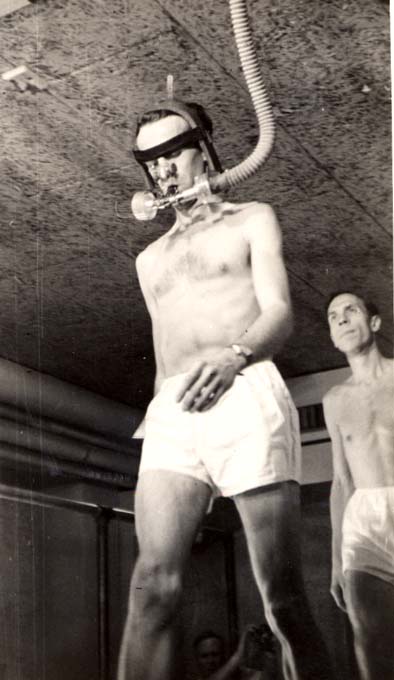

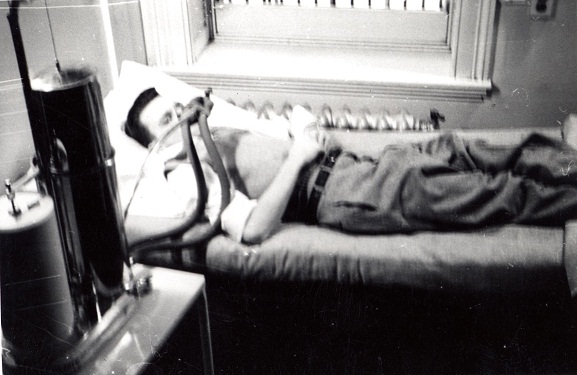

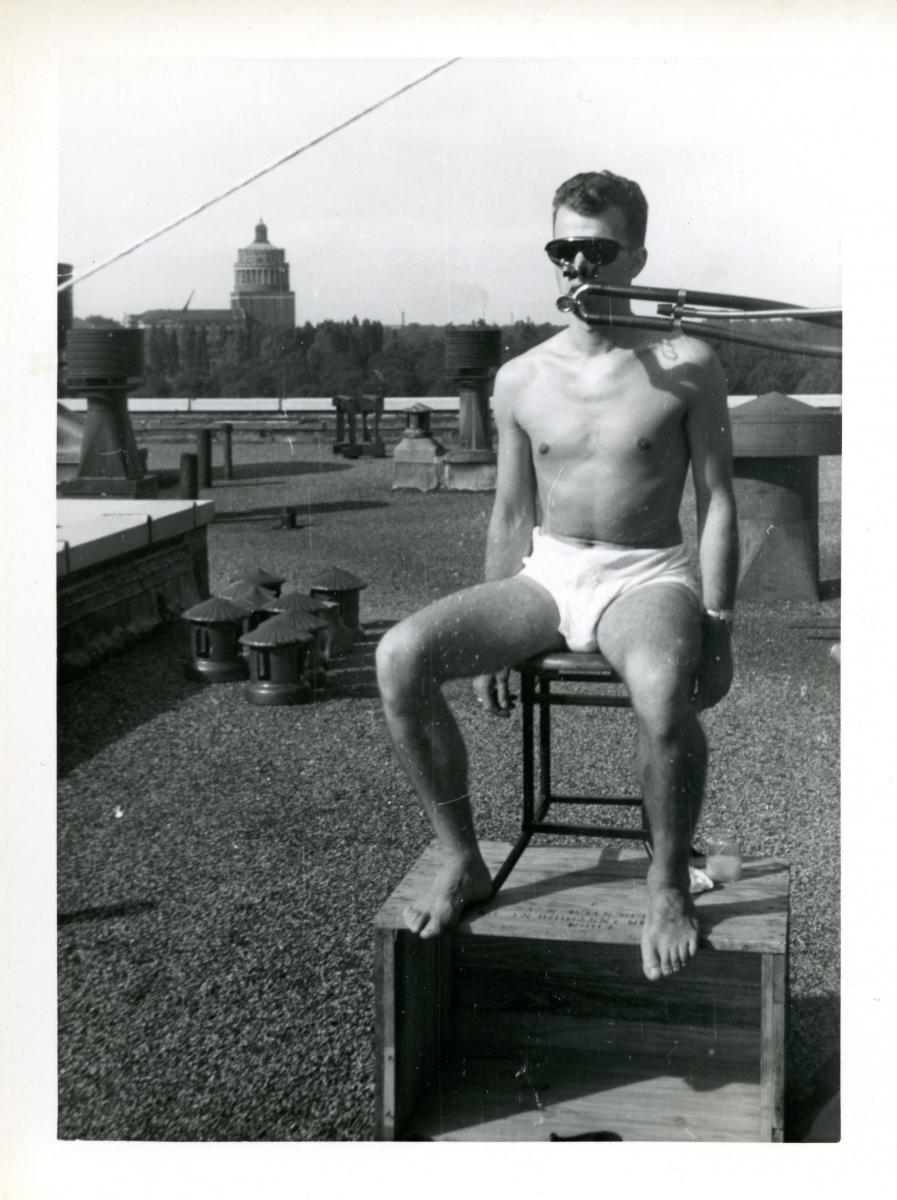

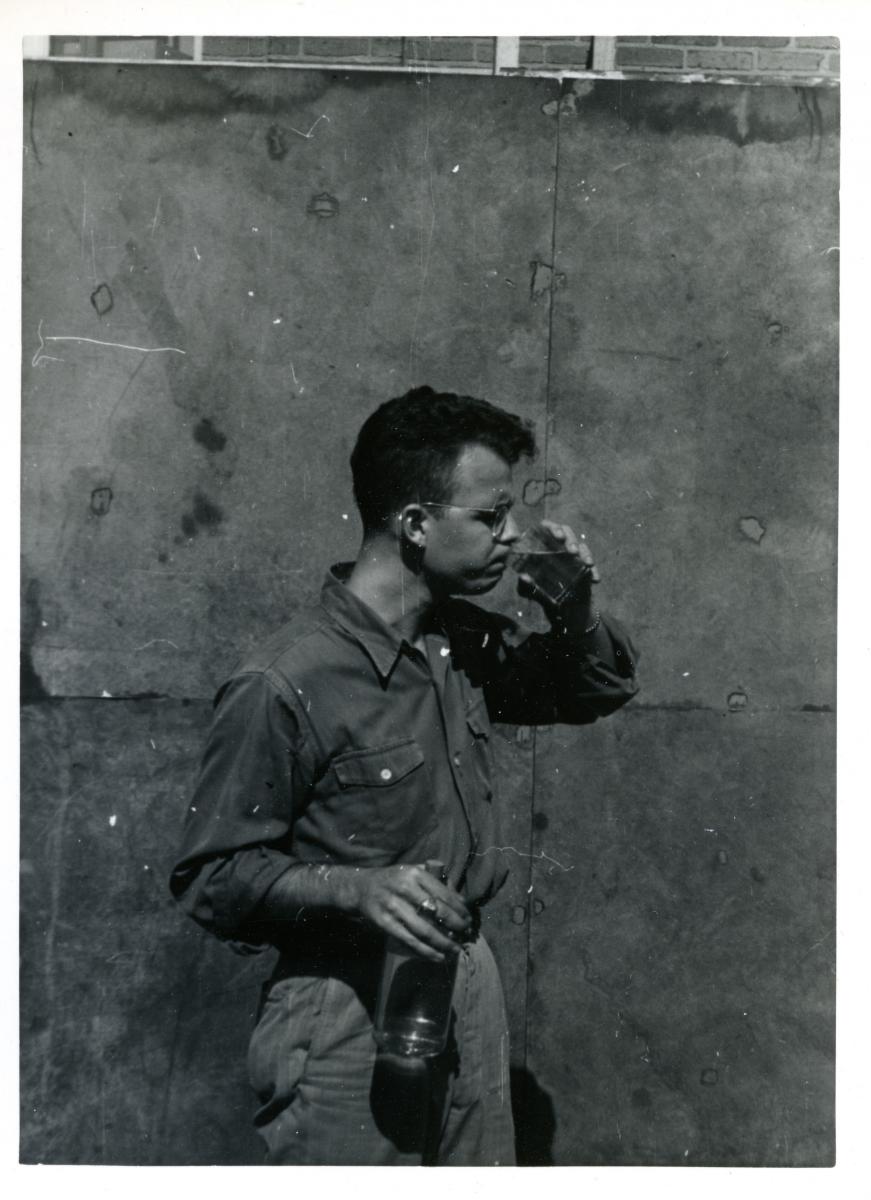

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 177th week of semi-starvation. Weight 119.5. (starting weight 2/12/45: 136.5). Nose clip, mask & hose used for controlling gas expelled during respiration. University of Minnesota Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene, Minneapolis, Minnesota.Digital image from the C.D. Smith Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Miscellaneous Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PennsylvaniaMarch 27, 1945

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 177th week of semi-starvation. Weight 119.5. (starting weight 2/12/45: 136.5). Nose clip, mask & hose used for controlling gas expelled during respiration. University of Minnesota Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene, Minneapolis, Minnesota.Digital image from the C.D. Smith Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Miscellaneous Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PennsylvaniaMarch 27, 1945 -

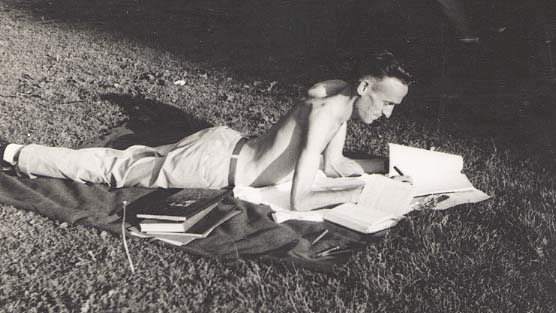

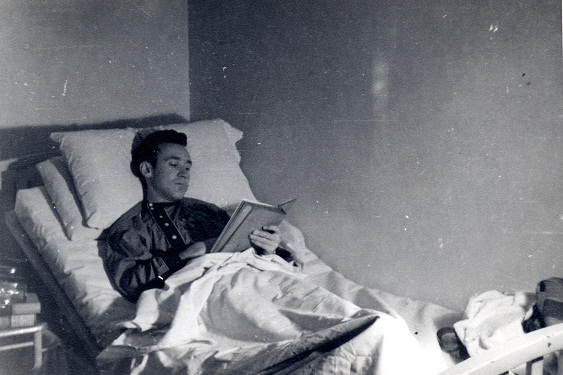

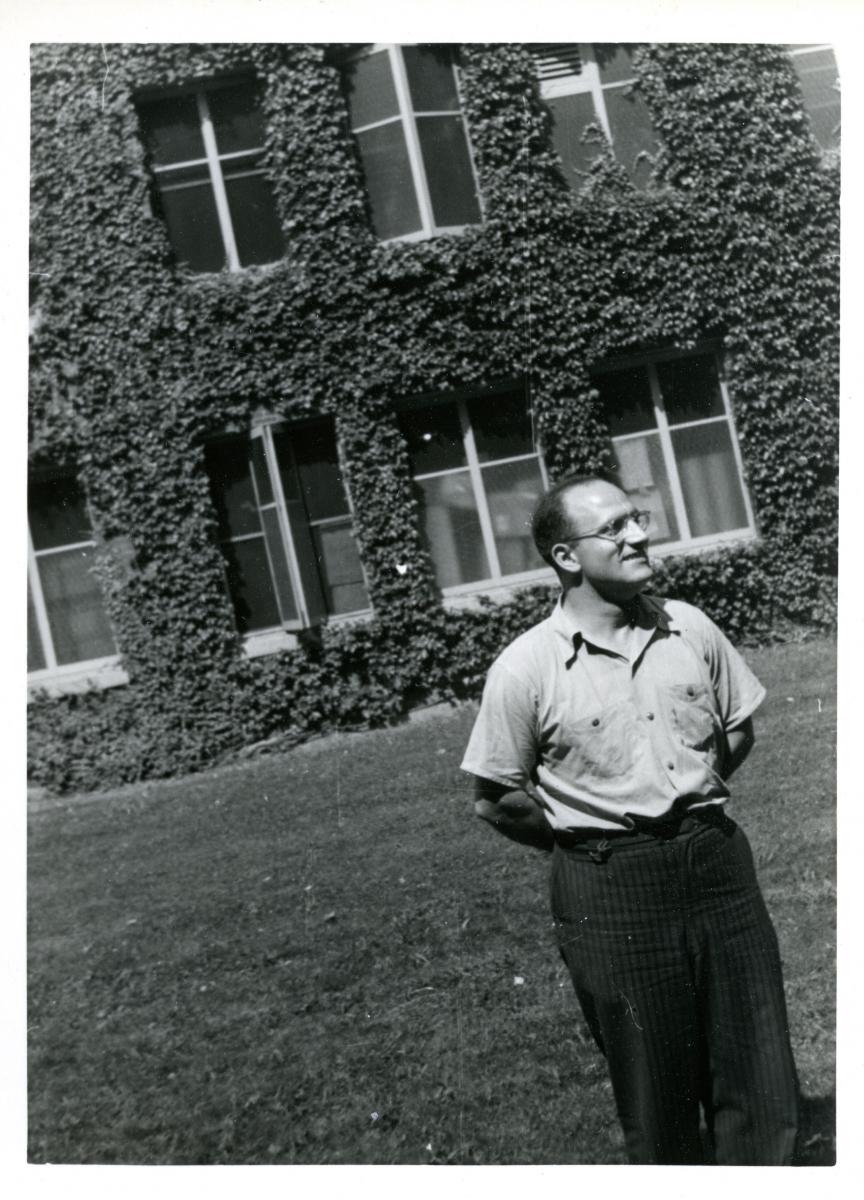

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 17University of Minnesota Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene, Minneapolis, Minnesota.Digital image from the C.D. Smith Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Miscellaneous Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 17University of Minnesota Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene, Minneapolis, Minnesota.Digital image from the C.D. Smith Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Miscellaneous Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10Taking water & air temperature for seawater experiment/s (Milton Gold). Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.Digital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10Taking water & air temperature for seawater experiment/s (Milton Gold). Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.Digital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945 -

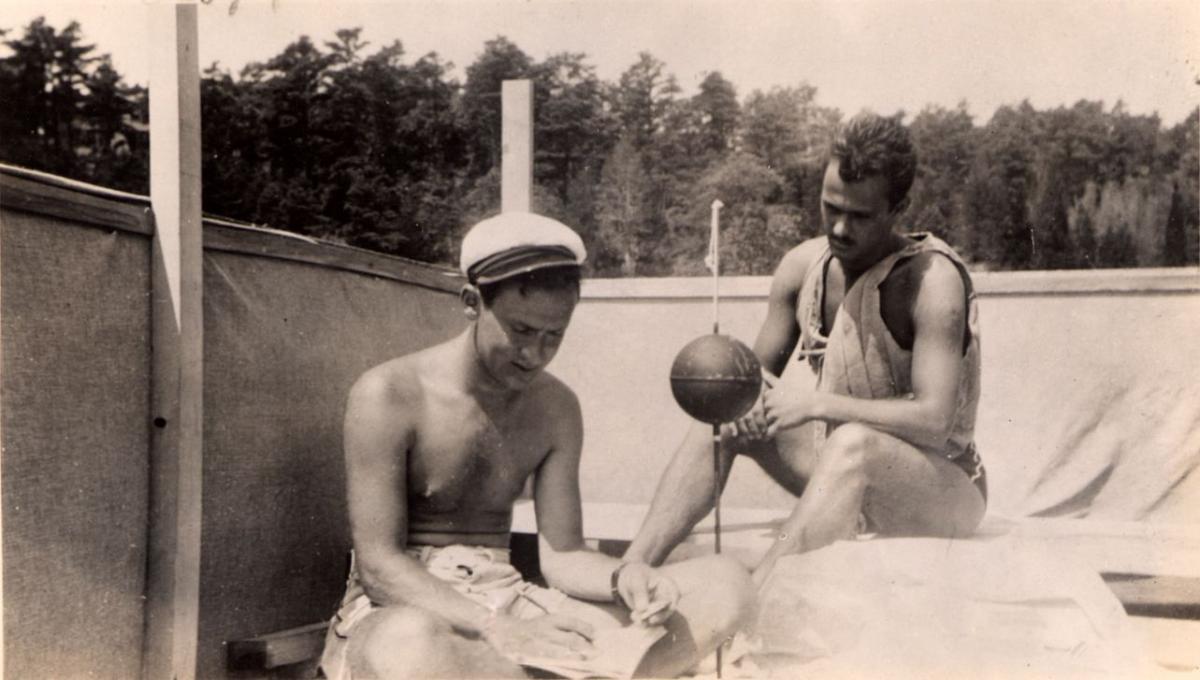

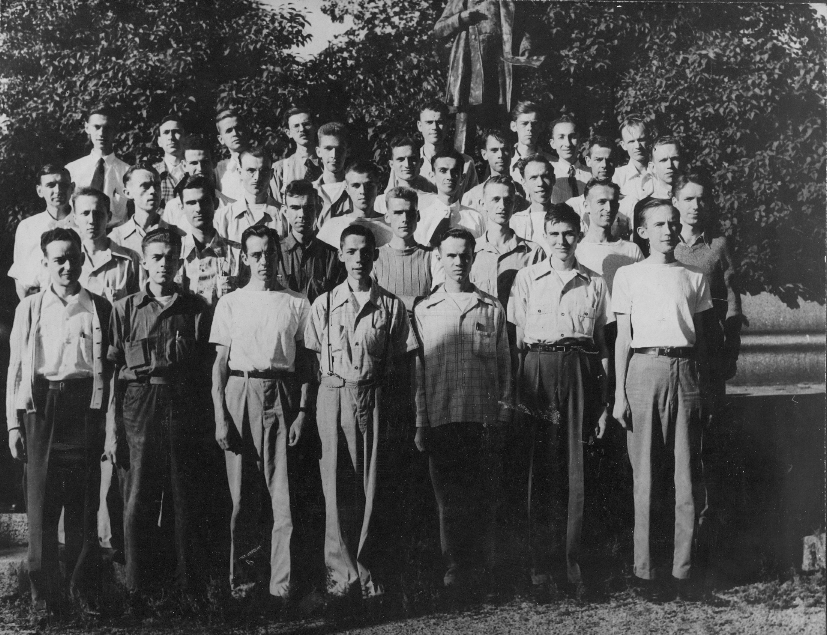

CPS Camp No. 115, subunits 17 & 18, University of Minnesota.Minneapolis Semi-starvation CPS unit.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.

CPS Camp No. 115, subunits 17 & 18, University of Minnesota.Minneapolis Semi-starvation CPS unit.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved. -

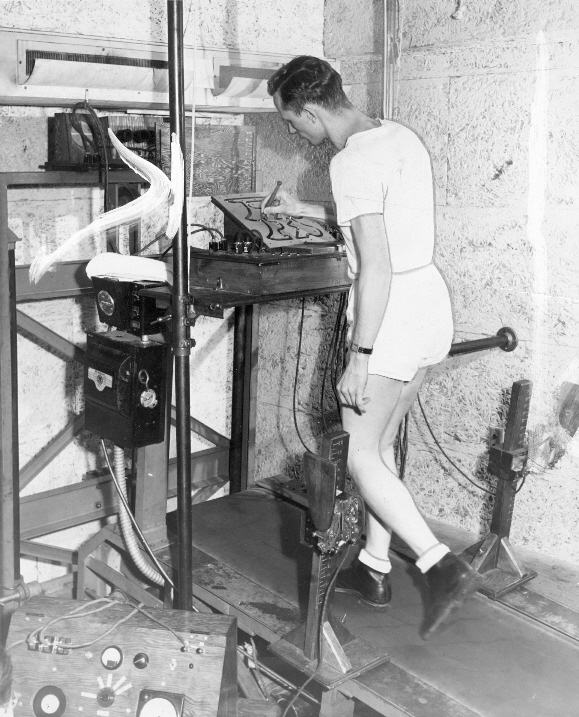

CPS Camp No. 115, subunits 17 & 18, University of Minnesota.Earl Heckman, from Rocky Ford, Colorado, on a treadmill as he takes electrical stylus through a pattern maze - tests coordination and records it automatically; February 28, 1945.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.February 28, 1945

CPS Camp No. 115, subunits 17 & 18, University of Minnesota.Earl Heckman, from Rocky Ford, Colorado, on a treadmill as he takes electrical stylus through a pattern maze - tests coordination and records it automatically; February 28, 1945.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.February 28, 1945 -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 30Civilian Public Service unit 115 human guinea pigs, at University of Illinois; front, left to right, Elmer Fricke, Howard Blosser, Dwane Houghan; back, left to right, George Nachtigal, Henry Tobyes, Paul Blosser.Digital image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansasca. 1945

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 30Civilian Public Service unit 115 human guinea pigs, at University of Illinois; front, left to right, Elmer Fricke, Howard Blosser, Dwane Houghan; back, left to right, George Nachtigal, Henry Tobyes, Paul Blosser.Digital image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansasca. 1945 -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 3Pulse was a newsletter published at Camp 115, subunit 3.Digital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 3Pulse was a newsletter published at Camp 115, subunit 3.Digital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33The Weekly Grunt was a newsletter published by the men at Camp 115, subunit 33, from July through September 1944.Digital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33The Weekly Grunt was a newsletter published by the men at Camp 115, subunit 33, from July through September 1944.Digital image from the American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG 002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

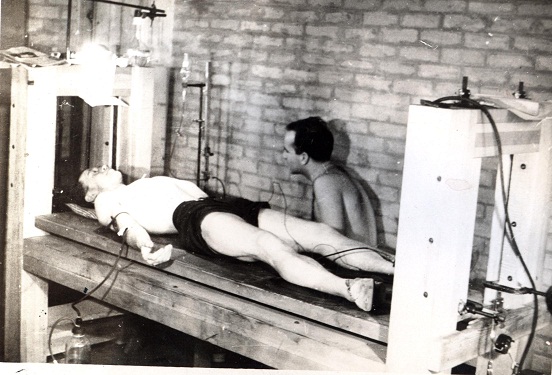

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21CPS man on tilt board during dehydration experiment.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21CPS man on tilt board during dehydration experiment.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

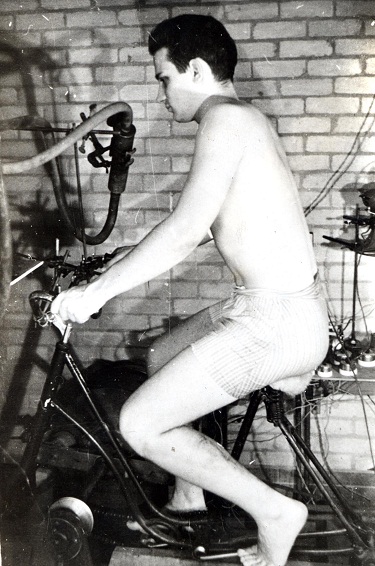

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21Man [Peter Watson?] riding on bike on dehydration against electrical brake, 10 minutes every hour.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21Man [Peter Watson?] riding on bike on dehydration against electrical brake, 10 minutes every hour.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

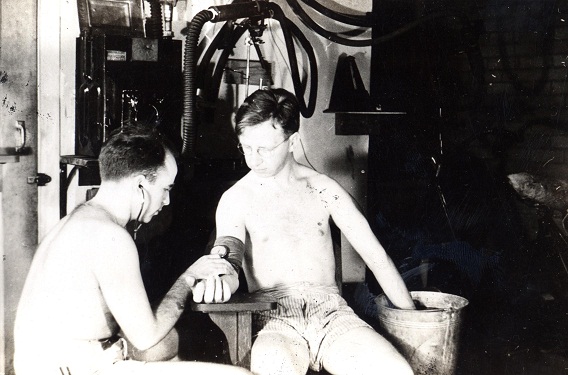

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21A pressure test. Effect on the system when a man in the heat and dehydrated, puts his hand in cool water.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21A pressure test. Effect on the system when a man in the heat and dehydrated, puts his hand in cool water.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21Taking blood from a CPS man in the heat to discover any unusual effects from taking blood when the veins are dilated due to heat.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21Taking blood from a CPS man in the heat to discover any unusual effects from taking blood when the veins are dilated due to heat.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10CPSer receiving injection before salt water experiment, 1943.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10CPSer receiving injection before salt water experiment, 1943.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10Salt Water experiment. Respirator mechanism, 1943.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10Salt Water experiment. Respirator mechanism, 1943.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10CPSer breathing into respirator during Salt Water experiment, 1943.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10CPSer breathing into respirator during Salt Water experiment, 1943.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10CPSer being hooked up? or blood pressure taken? for salt water experiment, 1943.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10CPSer being hooked up? or blood pressure taken? for salt water experiment, 1943.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10Milton Gold at Camp 115, subunit 10.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 10Milton Gold at Camp 115, subunit 10.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 179 C.O.’s are serving as ‘guinea pigs’ in experiments at the University of Minnesota to determine international standards regarding the minimum amount of vitamins necessary to sustain healthy adult life. Results should be valuable in making possible better use of available supplies, especially during the postwar period. Two of the men [George Cain and Walter Carlson] serve as lab technicians as well. 1943.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 179 C.O.’s are serving as ‘guinea pigs’ in experiments at the University of Minnesota to determine international standards regarding the minimum amount of vitamins necessary to sustain healthy adult life. Results should be valuable in making possible better use of available supplies, especially during the postwar period. Two of the men [George Cain and Walter Carlson] serve as lab technicians as well. 1943.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

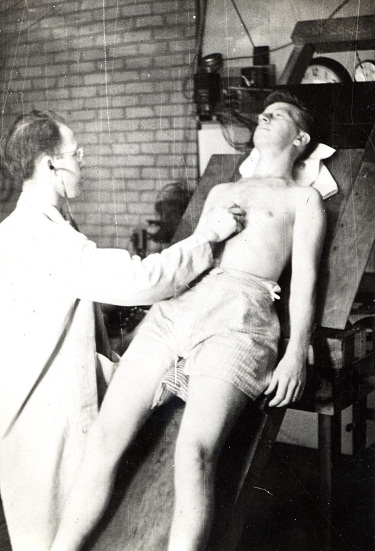

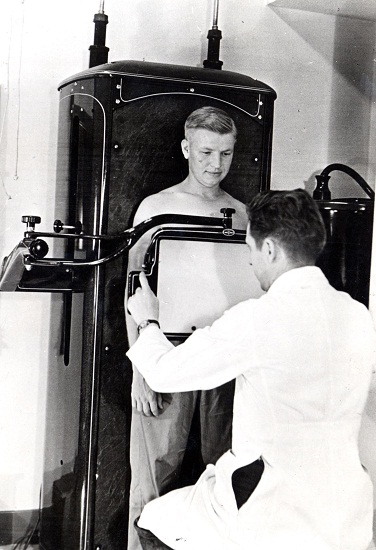

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 17Fluoroscope is used to check internal effects of a deficient diet. Norman Miller and Dr. Taylor.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 17Fluoroscope is used to check internal effects of a deficient diet. Norman Miller and Dr. Taylor.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

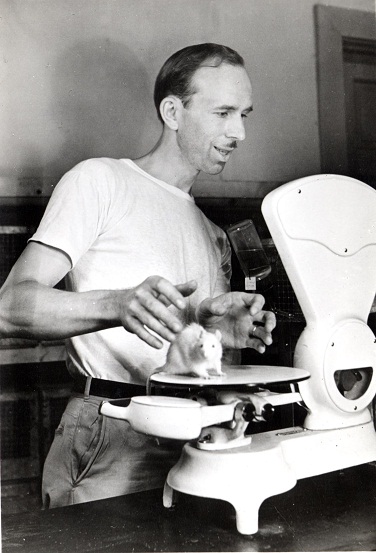

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 17Trevor Sandness weighing a mouse.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 17Trevor Sandness weighing a mouse.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 17Deficient diets taste good, but… Trevor Sandness, Walter Carlson, Norman Miller, Sel Copeland, Jack O’ Leary, Joe Blair, Wilbur Dunbar, George Caine, Harold Guetzkow.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 17Deficient diets taste good, but… Trevor Sandness, Walter Carlson, Norman Miller, Sel Copeland, Jack O’ Leary, Joe Blair, Wilbur Dunbar, George Caine, Harold Guetzkow.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

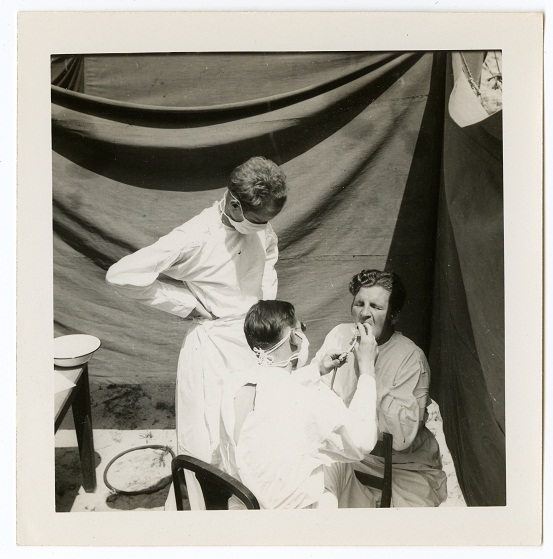

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Innoculation day at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Innoculation day at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233 -

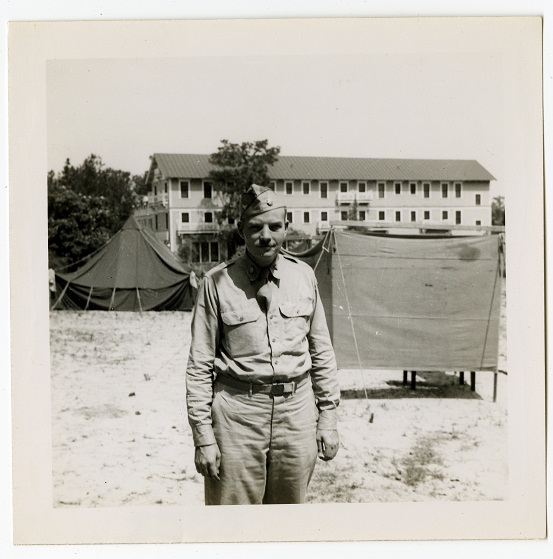

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33The "Boss", Major Abernathey, at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33The "Boss", Major Abernathey, at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233 -

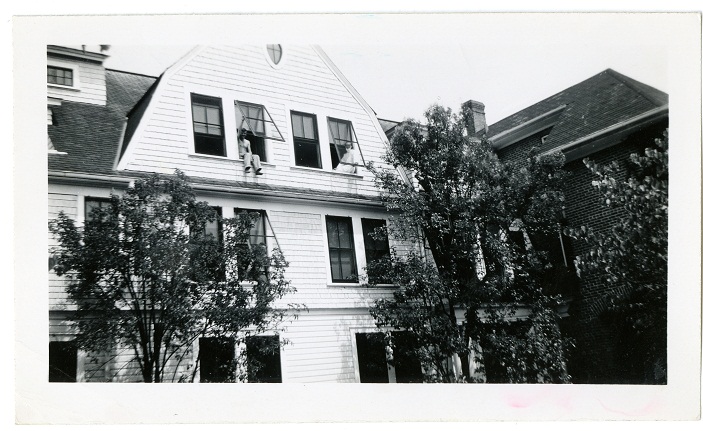

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Pinehurst, North Carolina.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Pinehurst, North Carolina.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233 -

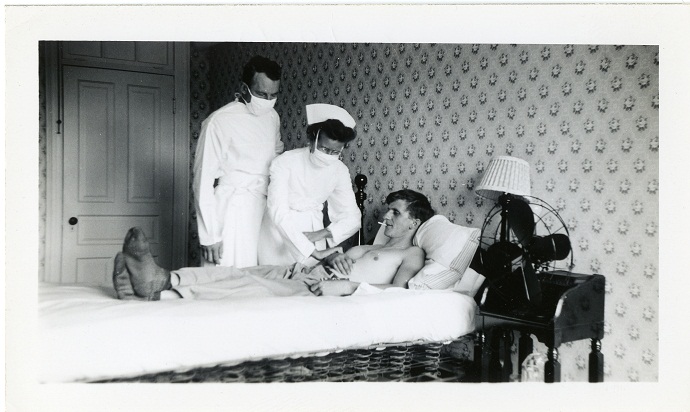

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Check up at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Check up at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233 -

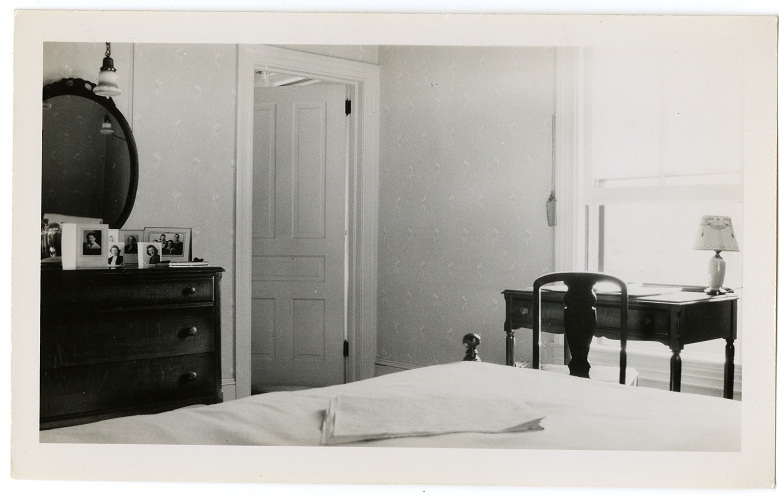

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Room at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Room at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233 -

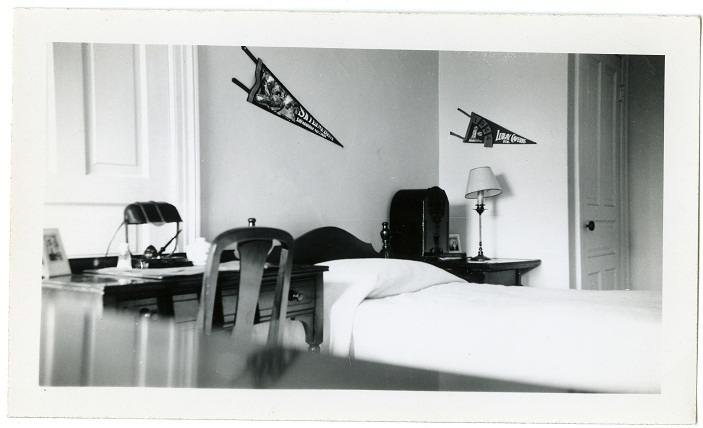

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Room at Pinehurst. One of the pennants reads "Luray Caverns".Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Room at Pinehurst. One of the pennants reads "Luray Caverns".Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233 -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Car at Pinehurst, North Carolina.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Car at Pinehurst, North Carolina.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233 -

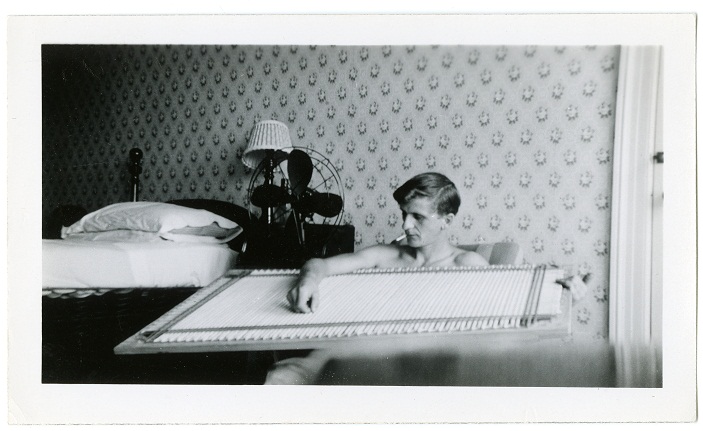

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Passing time at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Passing time at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233 -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Men in masks at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Men in masks at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233 -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Getting some sunshine at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 33Getting some sunshine at Pinehurst.Manchester University Archives and Brethren Historical Collection, Francis Barr CPS Collection, MC2011/233 -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 14"Mirl Whitaker. Cold Exposure Experiment. Rochester, NY. Strong Memorial Hospital. Sitting Posture, 4 hrs @ a time."Photo provided by Leo Baldwin.

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 14"Mirl Whitaker. Cold Exposure Experiment. Rochester, NY. Strong Memorial Hospital. Sitting Posture, 4 hrs @ a time."Photo provided by Leo Baldwin. -

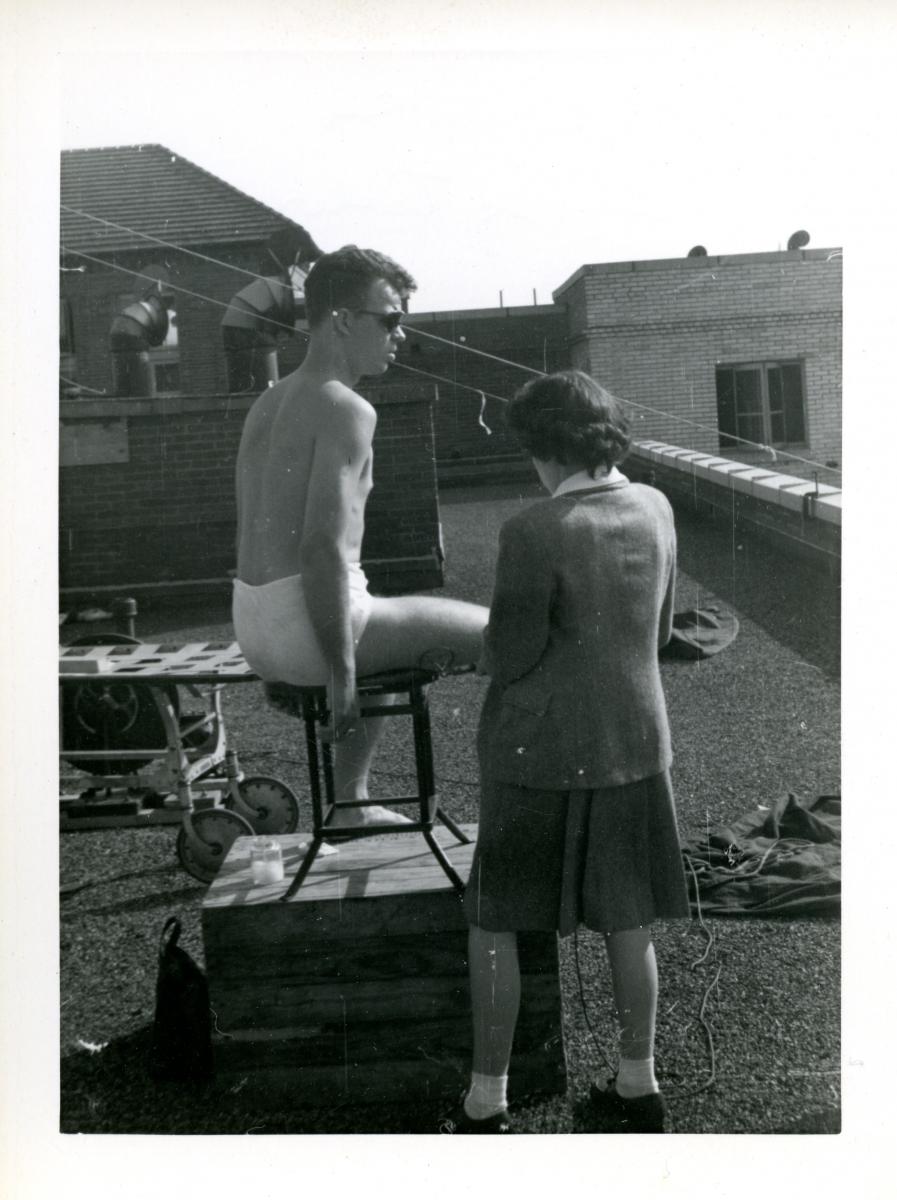

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 14Mirl Whitaker with lab technician.Photo provided by Leo Baldwin.

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 14Mirl Whitaker with lab technician.Photo provided by Leo Baldwin. -

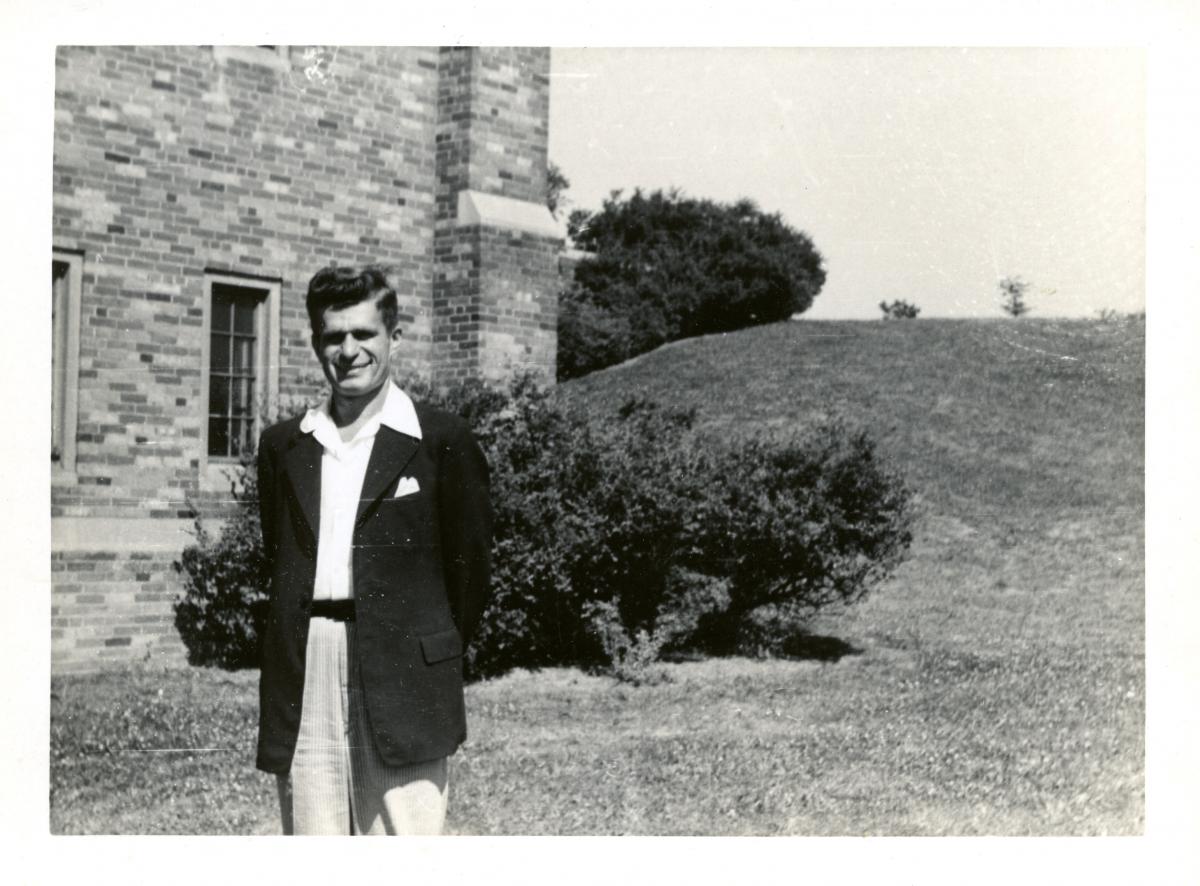

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21Harry KadetPhoto provided by Leo Baldwin.August 1945

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21Harry KadetPhoto provided by Leo Baldwin.August 1945 -

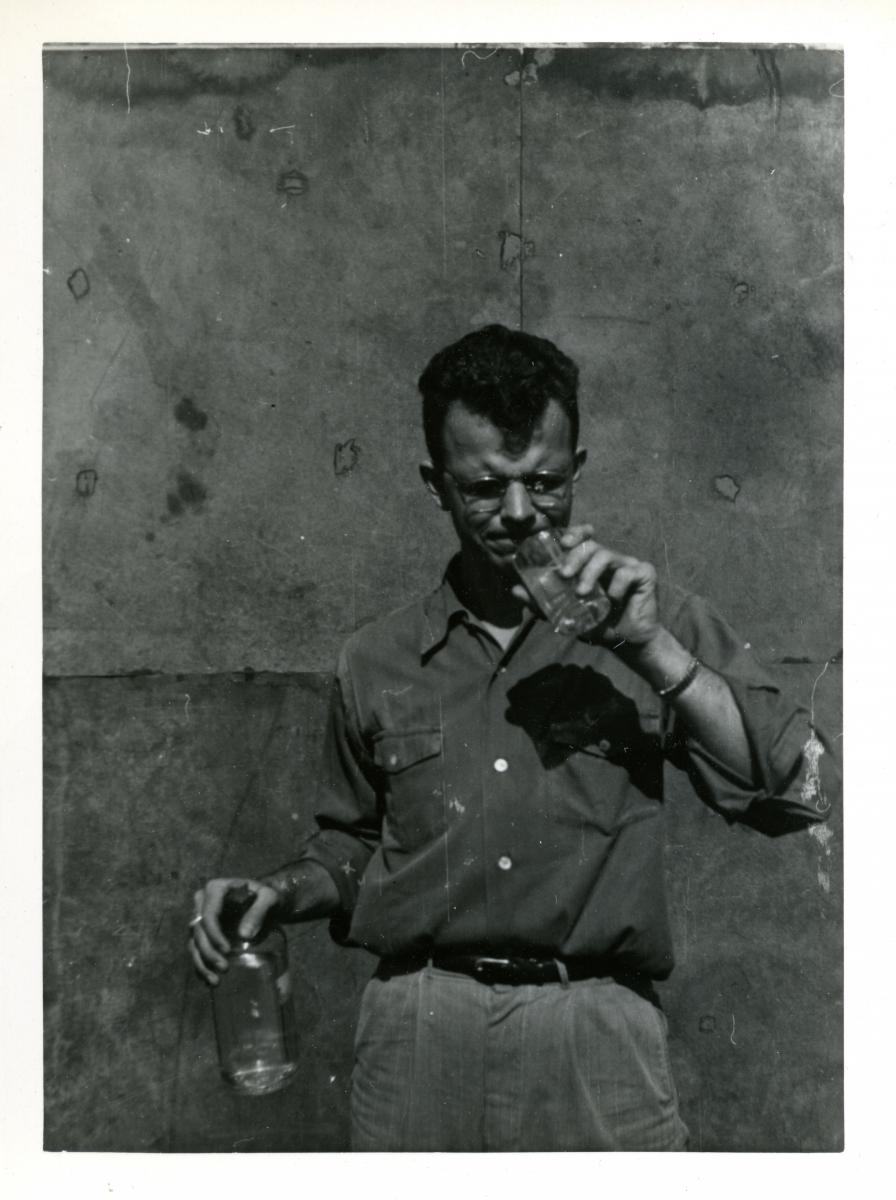

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21"Meryl Whittaker [sic]. Protein Deficiency Diet Experiment. Strong Memorial Hospital. Rochester, NY. Drinking diet element."Photo provided by Leo Baldwin.

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21"Meryl Whittaker [sic]. Protein Deficiency Diet Experiment. Strong Memorial Hospital. Rochester, NY. Drinking diet element."Photo provided by Leo Baldwin. -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21"Two of the unit men in the stand, the two on the left. On left--Mirl Whitaker. On right--Bob Jong."Photo provided by Leo Baldwin.

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21"Two of the unit men in the stand, the two on the left. On left--Mirl Whitaker. On right--Bob Jong."Photo provided by Leo Baldwin. -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21"Protein Deficiency Lab team. Mrs. 'Mac'--in charge of lab. Mertice Van Thof (Dr. Murlin's sec'y). At the picnic--Sept. (August) 1945."Photo provided by Leo Baldwin.

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21"Protein Deficiency Lab team. Mrs. 'Mac'--in charge of lab. Mertice Van Thof (Dr. Murlin's sec'y). At the picnic--Sept. (August) 1945."Photo provided by Leo Baldwin. -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21"Breaking the diet--August 1945. Around the table from left to right--Ray Stanley, George Spicer, Thad Scymansky[?], Dr. Murlin, Dr. Fried, Irvin Eller, Bob Dick, Mirl Whitaker, Bill Sowden[?], Roland Ortmayer, *Benglen (just the arm), *Baldwin--back to camera at right corner. (*not in this photo!)"Photo provided by Leo Baldwin.August 1945

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21"Breaking the diet--August 1945. Around the table from left to right--Ray Stanley, George Spicer, Thad Scymansky[?], Dr. Murlin, Dr. Fried, Irvin Eller, Bob Dick, Mirl Whitaker, Bill Sowden[?], Roland Ortmayer, *Benglen (just the arm), *Baldwin--back to camera at right corner. (*not in this photo!)"Photo provided by Leo Baldwin.August 1945 -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21Oral FisherPhoto provided by Leo Baldwin.

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21Oral FisherPhoto provided by Leo Baldwin. -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21Amos CulpPhoto provided by Leo Baldwin.September 1945

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21Amos CulpPhoto provided by Leo Baldwin.September 1945 -

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21"Mirl Whitaker--Amino Acid"Photo provided by Leo Baldwin.

CPS Camp No. 115, subunit 21"Mirl Whitaker--Amino Acid"Photo provided by Leo Baldwin.

-

-

March 27, 1945

March 27, 1945 -

-

1945

1945 -

-

February 28, 1945

February 28, 1945 -

ca. 1945

ca. 1945 -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

August 1945

August 1945 -

-

-

-

August 1945

August 1945 -

-

September 1945

September 1945 -

CPS Unit 115, subunits 17 and 18, were located in the Experimental Laboratory of Physical Hygiene housed in Memorial Stadium at the University of Minnesota. Both men and staff entered the stadium through Gate 27. The laboratory work rooms, offices, dormitory accommodations for the men, study rooms and a large recreation hall were all under the stadium. Meals were served in Shevlin Hall, a short distance away on the campus.

Director: Ancel Keys directed the experiments and W. Jarrot Harkey served as assistant director of the assignee group.

For the “Minnesota Experiment”, Keyes carefully picked assignees interested in addressing the problem of hunger from CPS units across the country to be subjects in an experiment to address rehabilitation from starvation. The group consisted of thirty-six men from eleven Christian denominations (one a Mennonite) one Jewish man and two with no denominational affiliation. They entered CPS from eighteen different states.

Nine additional men served as special assistants to the research team.

The men, interested in relief work, in addition to serving as subjects, would participate in foreign relief training.

The men served as subjects and technicians in a nutrition experiment involving starvation and rehabilitation. The aim of the study was to use the laboratory results to formulate a set of recommendations that could be applied to relief work in areas of famine caused by war. The experiment was organized in three phases.

- The first was a standardization or control phase consisting of twelve weeks to adjust diet, activity, and living conditions for all subjects so that a state of “normal” could be established by test results prior to the second phase.

- The second phase, starvation, consisted of twenty-four weeks during which the subjects were fed a diet approximating the war-famine diet of north central Europe (bread, potatoes, cereals, turnips, cabbage with only “token amounts of meat and dairy products”) served in two meals per day except for Sunday when only one meal was served. The diet averaged 1,570 calories per day, and the men lost on average 24.29 percent of their body weight.

- In phase three, rehabilitation, the men were divided into four groups and fed diets with different amounts of protein, calorie and vitamin content. This phase lasted twelve weeks.

The results contributed to a two volume report The Biology of Human Starvation, on rehabilitation of victims of starvation. (Eisan pp. 310-312, Kreider, p. 18)

The men endured hundreds of tests and measurements to assess physiological, psychological, metabolic, psychomotor, and other performance measures. For the control phase and the first part of semi-starvation, the men were free to come and go during “off hours” or when not in required sleep. A “buddy system” was then introduced, requiring the presence of a buddy whenever off premises, as a result of the severe stress “of resisting the temptation to break the diet”. The system was in place through the sixth week of rehabilitation.

The men were regularly involved in periods of treadmill exercise and walked twenty-two miles each week. They also performed other assigned tasks such as housekeeping, laundry work, assistance in the workshop, tabulating and other related duties. They attended frequent meetings of the whole group for staff to communicate information, respond to questions and deal with complaints.

The men suffered physically and psychologically during the ordeal. While not regarded as ethically problematic in the 1940s, the Nuremberg Code, established in 1949 to address the Nazi medical experiments, established a guide for the conduct of research on humans. C. Everett Koop, Surgeon General of the United States in the Reagan administration, reflected that the CPS human guinea experiments would not have been allowed today. (Taylor p. 85, PBS Documentary The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight it)

The men in the camp were deeply committed to their participation as a way to address a major humanitarian need resulting from war. They also had high interest in postwar relief work.

As a result, a major educational emphasis for the unit was preparation for foreign relief service. Not only did men avail themselves of courses at the university, but also a number of courses were designed with the assistance of university extension services (Local Governments of Western Europe and Topics in Social Work, as examples). Men studied foreign languages, participated in lecture series on public health conditions in foreign countries, and divided into six special topic study groups. The latter proved less successful as the men became debilitated during the severe stress of the experiment.

The men also conducted applied work in various kinds of community groups—settlement houses, youth centers, an interracial co-op store. In addition a number of the men, particularly before the effects of the starvation phase set in, participated in a food packaging program for European relief.

Some men participated in theatre and musical productions at the university. Others assisted in local churches in the Twin Cities and on group in the unit initiated several informal devotional and worship services.

The unit also organized a local chapter of the CPS Union, focusing on a poll to ascertain public reaction to the conscientious objector, the results of which were surprisingly favorable.

The men published Guinea Pig Gazette beginning in May 1943 continuing through 1944. Those who participated in CPS Unit 140.07 used the same title for their unit publication.

Eisan, in his review of the starvation experiments, highlights some of the practical value of the studies.

- Official delegations from Canada, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, England, India, China, the Netherlands, East Indies, Brazil, Chile, Puerto Rico, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Belgium, France, Switzerland and Poland visited and contacted the laboratory to consult on application of results to the actual day-to-day problems in many parts of the world.

- The United States Departments of State, War and Agriculture extensively used findings from the Minnesota Experiments.

- The Committee on Emergency Food Problems focused on the study results in a December 1946 memorandum entitled “Calorie Consumption Levels and Their Relation to Health, Well-being and Capacity for Work”.

Eisan noted application of findings in several areas:

- diagnosing degree of under nutrition in individuals and population groups,

- knowledge of work capacity of underfed people,

- understanding of psychological problems,

- medical dangers in semi-starvation, caloric needs for rehabilitation,

- the place of special vitamin and protein supplements in rehabilitation,

- and the persistence of starvation effects. (pp. 310-312)

Further, the study also proved useful in later medical research focused on the treatment of anorexia nervosa. (Tucker pp. 199-200)

For information on Brethren service in human guinea pig experiments, see Leslie Eisan, Pathways of Peace: A History of the Civilian Public Service Program Administered by the Brethren Service Committee. Elgin, IL: Brethren Publishing House, 1948, Chapter 9, The Minnesota Experiment in Starvation and Rehabilitation, pp. 296-312; Appendix, p. 459.

Brethren Historical Library and Archives at Elgin, IL brethrenarchives@brethren.org

For information on Mennonites in human guinea pig experiments, see Melvin Gingerich, Service for Peace: A History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service. Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee printed by Herald Press, Scottdale, PA, 1949 pp. 270-273.

See also J. Kenneth Kreider, A Cup of Cold Water: The Story of Brethren Service. Elgin, IL: Brethren Press, 2001, Chapter 2.

Life Magazine , “Men Starve in Minnesota: Conscientious Objectors Volunteer for Strict Hunger Tests to Study Europe’s Food Problem” (July 30, 1945).

The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight It: The Story of World War II Conscientious Objectors, 2001, a PBS documentary. www.pbs.org/thegoodwar.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952, Chapter VII: The Service Record of Conscientious Objectors, pp. 124-151.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Human Guinea Pigs in CPS Detached Service, 1943-1946, List Compiled by Anne M. Yoder, Archivist, November 2010. http://www.swarthmore.edu/Library/peace/conscientiousobjection/CPSResources/MEDICAL%20RESEARCH.pdf

See also Steven J. Taylor, Acts of Conscience: World War II, Mental Institutions, and Religious Objectors. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2009, pp. 80-88.

See Todd Tucker, The Great Starvation Experiment: Ancel Keys and the Men Who Starved for Science. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.