CPS Unit Number 103-01

Camp: 103

Unit ID: 1

Title: Missoula

Operating agency: MCC

Opened: 5 1943

Closed: 4 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 262

-

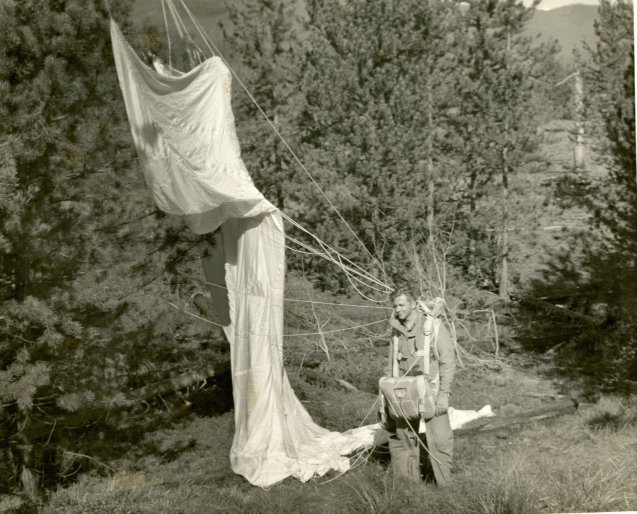

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaSmokejumper 431603. Parachute caught in a tree, 1945Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaSmokejumper 431603. Parachute caught in a tree, 1945Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945 -

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaSmokejumper 431684. Parachuting view from PlaneDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaSmokejumper 431684. Parachuting view from PlaneDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

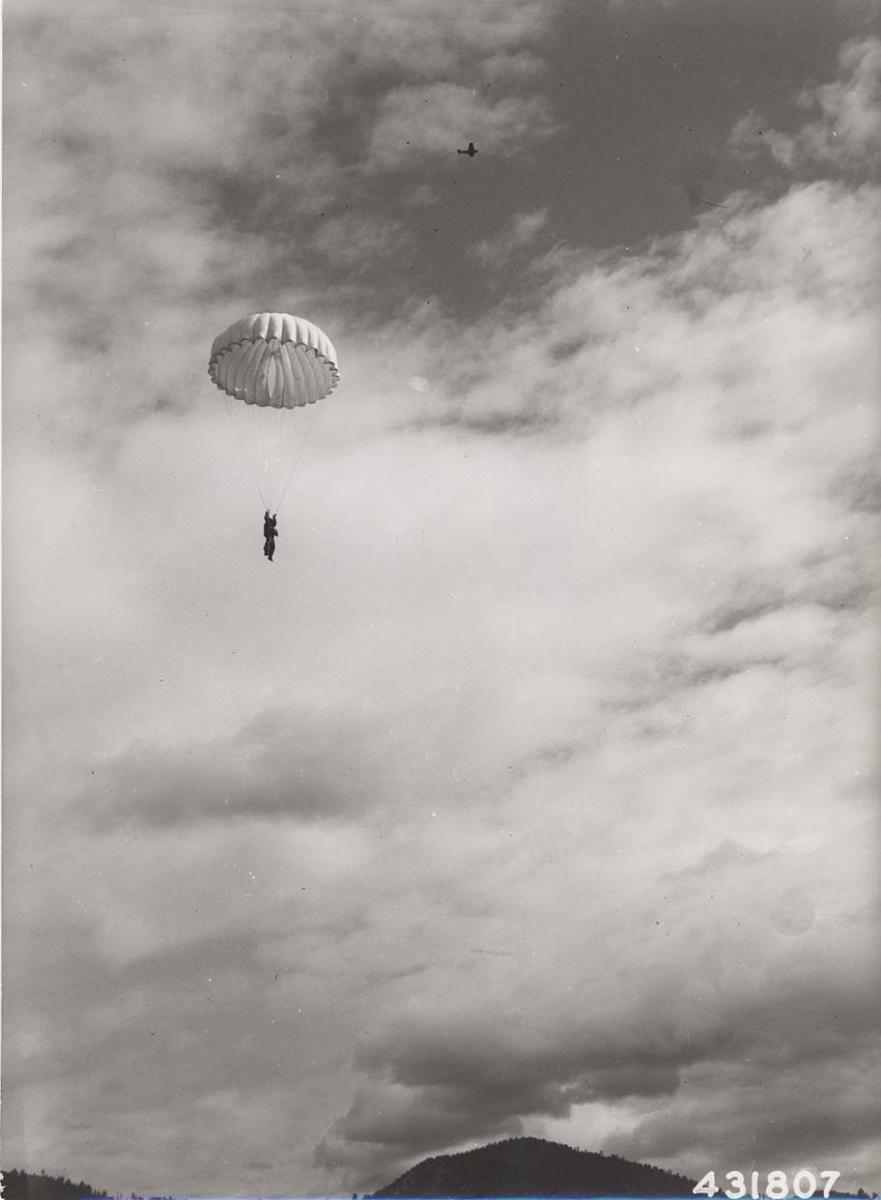

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaSmokejumper 431807Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaSmokejumper 431807Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945 -

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaSmokejumpers stitching up parachutesDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaSmokejumpers stitching up parachutesDigital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania1945 -

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaDale Yoder at CPS Camp 103. Accurate steering cannot be done and gusty winds may cause the jumper to land among the trees. Although the silk materials of the parachutes are unusually strong, repairs must frequently be made on them before they're repacked.Photo 59 Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaDale Yoder at CPS Camp 103. Accurate steering cannot be done and gusty winds may cause the jumper to land among the trees. Although the silk materials of the parachutes are unusually strong, repairs must frequently be made on them before they're repacked.Photo 59 Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

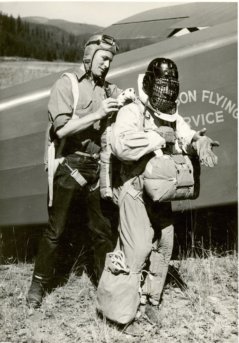

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaCivilian Public Service camp 103, Missoula, Montana. Left: Glenn Smith, Forest Service, Squad Leader. Right: Harry Mishler.Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaCivilian Public Service camp 103, Missoula, Montana. Left: Glenn Smith, Forest Service, Squad Leader. Right: Harry Mishler.Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaCivilian Public Service camp 103, Missoula, Montana. The horizontal ladder. Part of the obstacle course. Left to right: Oliver Huset, George Leavitt.Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaCivilian Public Service camp 103, Missoula, Montana. The horizontal ladder. Part of the obstacle course. Left to right: Oliver Huset, George Leavitt.Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaCivilian Public Service camp 103, Missoula, Montana. A jump from the training tower simulates jumping from a plane. The same procedure and technique is followed as in a real jump, and the shock when the rope pulls taut is approximately equivelant to the opening shock of the parachute.Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaCivilian Public Service camp 103, Missoula, Montana. A jump from the training tower simulates jumping from a plane. The same procedure and technique is followed as in a real jump, and the shock when the rope pulls taut is approximately equivelant to the opening shock of the parachute.Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaCivilian Public Service camp 103, Missoula, Montana. Training.Photo 293 Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaCivilian Public Service camp 103, Missoula, Montana. Training.Photo 293 Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaCivilian Public Service camp 103, Missoula, Montana. Smoke Jumpers Camp. As soon as jumpers are dropped to a fire, a mule string carrying additional food supplies starts out to the scene via trail.Photo 60 Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaCivilian Public Service camp 103, Missoula, Montana. Smoke Jumpers Camp. As soon as jumpers are dropped to a fire, a mule string carrying additional food supplies starts out to the scene via trail.Photo 60 Box 2, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaLew Berg, Civilian Public Service smoke jumperDigital image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansasca. 1944

CPS Camp No. 103, Missoula at Huson, MontanaLew Berg, Civilian Public Service smoke jumperDigital image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansasca. 1944

-

1945

1945 -

-

1945

1945 -

1945

1945 -

-

-

-

-

-

-

ca. 1944

ca. 1944

CPS Camp No. 103, a Forest Service base camp in Missoula, Montana operated by Mennonite Central Committee in cooperation with the Brethren and Friends Service Committees, opened in May 1943 and closed in April 1946. Men in the unit, highly trained, parachuted into rugged country to put out forest fires; in down times they performed prevention work.

The first smoke jumper training camp was located at the Seeley Lake Ranger Station, over sixty miles northeast of Missoula, Montana.

Later the training relocated to Camp Menard, an abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camp, about a mile north of the Ninemile Remount Depot at Huson, Montana. Huson, about thirty miles northwest of Missoula, became headquarters for the camp in July 1943. Here, when not fighting fires, the men spent much time “putting up hay” to feed hundreds of pack mules that carried supplies and equipment to guard stations and to and from fires.

In order to work fires, men organized into squads of eight to fifteen were stationed at six strategic points, also known as spike camps: Seeley Lake, Big Prairie and Ninemile in Montana; Moose Creek and McCall in Idaho; and Redwood Ranger Station in southwestern Oregon at the edge of Cave Junction. The men worked from other spike camps as well, including some in Washington State. Some men lived in Missoula.

The crew based at Seeley Lake covered Forest Service Region I, an area of eight million acres lacking roads. Airfield services based in Missoula serviced the area. The men also fought many fires in Regions IV and VI.

Directors: Roy E. Wenger, Arthur J. Wiebe

Dietician-Nutricianist: Florence Heineman Wenger

Matron: Evelyn Wiebe

Nurse: Catherine Harder

Nurse-Matron: Marie Ediger

More than three hundred men expressed interest to their respective service committee (Brethren, Friend, or Mennonite). The service committees sent one hundred and eighteen applications forward to the Forest Service, each with physical examination reports and recommendations from camp superintendents. One government official noted that they could have used all of the men if equipment and supplies had been available for more than the sixty selected, twenty each from AFSC, BSC and MCC camps and units.

The men, highly diverse in education, religious affiliation, geographic origin and prior occupations, and all committed to this particular “work of national importance”, maintained high morale during the life of the camp. Matthews reports that they continued to face subtle prejudice, with some trouble between regular Forest Service employees and the COs. Supervisor Earl Cooley, who originally had doubts about CPS men, and several other officials agreed to work out the problems in the field.

We thought these men would be hard to handle, independent, and renegades . . .but they were just the opposite. The Mennonites were almost all Midwest farm boys who had never been away from home. They were used to working hard from daylight to dark and could not understand eight-hour work laws. . . . Before the CPS program broke up we had excellent working relations with all the CPS units. (Cooley, Trimotor and Trail, 51 in Matthews p. 121)

Nearly two hundred and forty men served as smokejumpers, not realizing at the time that their work “helped revolutionize wildland firefighting”.

The idea for CPS men to serve as smoke jumpers occurred to Phil Stanley, a Friend assigned to CPS Camp No. 37 at Coleville, California, after he heard Ray Breeding, an engineer at the Mono National Forest describe the new method of fighting fires by landing parachutists near the scene. Disenchanted with CPS projects that he viewed as worthless, or even “work of national impotence”, he started writing letters. One alerted his brother Jim, based in Washington, D.C. with the National Service Board for Religious Objectors to write and edit “The Reporter”. He asked him to alert the service committees to the possibilities. The other, he directed to Axel Lindh, head of Fire Control for Region One on October 2, 1942:

It occurred to me some three months ago that you might need men for your parachute fire-fighting corps, either for experimental purposes or for the actual fire fighting. . . .

We are all drafted men, pretty well fit physically, self-supporting, and have had a moderate amount of fire fighting (mostly in the East). The fires . . .were probably nothing like the ones that require parachute tactics and we would probably need more training both physically and tactically. . . .

If there is the slightest possibility of your being able to use us, we would appreciate more information concerning requirements, the type of forests adaptable to this technique, location of the training school, and any details that you consider useful. Of course, if you can use us, the project will have to be okayed by Selective Service and the Friends Service Committee in Philadelphia. (in The Smoke Jumper, p. 30)

Lindh, on receipt of the letter, initiated contact with Selective Service and the National Service Board of Religious Objectors. He responded to Stanley, “So far as the Forest Service officials here in this region are concerned, we will be mighty glad to recruit parachute firefighting candidates from the Civilian Public Service camps.” (in Gingerich, p. 140)

The National Service Board of Directors approved plans for the unit March 8, 1943. The Forest Service agreed to provide maintenance, cots, blankets and sleeping bags, housing for Roy and Florence Wenger (director and dietician) as well as an assistant, a nurse and six cooks. They also doubled the pay for the men from $2.50 per month, but “encouraged the men to use the extra money to buy health insurance since the Forest Service refused to cover them”. (Matthews p. 107-108)

The War Department released some parachute cloth and Forest Service supervisors used “depression years experience” to improvise.

Five men from each of the three church agencies reported to Camp Paxson, a Boy Scout Camp on Seeley Lake over sixty miles north and east of Missoula. There they began two weeks of intensive training in parachute rigging in early May 1943. In training, men learned different types of parachutes, how to repair, pack and fold them for use. The first group of thirty-three men began jumper and rigging training on May 17 which continued for a month.

Following that phase, men entered ground, fire control and first aid training. In this rigorous phase, men performed calisthenics before breakfast, followed by workouts on an obstacle course after breakfast, along with other conditioning activities in preparation for the tower jump. Fully equipped men jumped from a twenty-five foot tower harnessed by a large rope attached to the overhead beam. The rope stopped their fall five feet above ground. This training lasted for two weeks prior to actual jumping from an airplane.

Following seven training jumps from a plane, men were then sent to fight fires. See Robert C. Cottrell’s Smokejumpers of the Civilian Public Service in World War II for sixteen of the men’s personal descriptions of their training.

“During the 1943 training sessions, approximately 500 parachute jumps were performed with nine lost-time accidents, of which five were serious enough to prevent men from regaining their lost training”. Men suffered sprained ankles most frequently, with the most serious injuries being broken bones in a foot. One man suffered a concussion and required extensive hospitalization. If men could not return to jumping, they served in lookout towers. (Gingerich p. 143)

Catherine Harder, camp nurse, reported that “men in her infirmary were eager to get back into training” even though the physical training resulted in many injuries. Harder began her nursing career working with the smoke jumpers. (Goossen p. 82-83)

Each man carried basic equipment of a Pulaski (combination ax and mattock), a shovel, canteen, and two-day supply of K rations. Their suits, specially constructed and heavily padded, as well as helmets and boots helped to protect them during jumps. It was not unusual to land in trees, so men trained in how to work their way down to the ground.

When a fire call sounded, men suited up, rushed to the air field, and boarded the plane. After locating the fire, the pilot flew over and around it to give the spotter time to select the most suitable landing place. He threw a drift chute to test direction of air currents. Then the plane circled and the men prepared to jump, the first man at the door waiting for the signal.

The pilot cuts the motor, the signal comes, the muscles in the jumper’s arms and shoulders tighten, he pulls himself out of the door and starts falling through space, down, down—and then a terrific jerk, as his parachute opens over him. After he floats gently (he hopes) to the ground. (Smoke Jumper’s Load Line, September 1943, p.3 in Gingerich p. 144)

Of course the landing created the most dangerous moment as logs, rocks, and trees needed to be dodged. The jumper bent his knees slightly preparing to roll on landing, get up quickly, deflate the chute and start undoing the gear, before determining where he had landed in relation to the fire. On occasions men needed to hike long distances to reach a fire.

A mule pack train brought in additional food and carried back chutes and equipment in the case of large fires. The men, well trained in methods of fire control, chopped, raked, and dug fire lines to stop the spread of fire, ever on the lookout for the dreaded crowning of a fire. When they brought the fire under control, they often had to hike miles to be picked up.

The Bell Lake fire of September 10, 1944, located at high altitude on the divide between Idaho and Montana, required twenty-nine smoke jumpers plus nine additional men, six plane-loads of food and equipment dropped in a meadow near a lake a half-mile from a portable fire camp. It took the men several days to suppress the fire.

In 1943, the men suppressed thirty-one fires; in 1944 more than seventy. By September 1945, the Missoula region attacked 179 fires. In addition men fought many fires in Regions IV and VI. P. D. Hanson, regional forester in Missoula wrote Arthur Wiebe, Camp Director in December 1945 about the severe 1945 fire season with 1,200 forest fires.

Even so, our total area of burned forest at the close of the season was small. Such an accomplishment was made possible by the splendid action of our air-borne firemen, the smoke jumpers. Many of the 181 fires our jumpers suppressed in the nation’s most remote wilderness could have become catastrophic had the jumpers not performed expertly and efficiently. To them goes a large share of the credit for a nationally important job well done. (Static Line, January 26, 1946 pp. 2-3 in Gingerich p. 146)

When not fighting fires, the men built fence, a plane hangar or a shed; cut lumber, constructed trails and telephone lines; maintained roads or improved ranger stations. They cut much hay to feed the pack mules.

Florence Heineman Wenger, camp dietician and wife of Roy Wenger, camp director, an athletic and physically fit woman almost became the first female smoke jumper. She worked out with the men each morning at seven-thirty, and fell in with the men for calisthenics forty-five minutes later. She had no trouble with the obstacle course. “’The men all supported her’—especially the Quakers, whose sect had preached equality for women since the 1600s.” (Roy Wenger report in Matthews p. 130)

In her memoir, Florence reported that she joined the guys “to keep busy”. She was ready for the practice jumps, but not permitted to jump, a real disappointment as “no official seemed willing to take the responsibility for letting her go further”. It would be nearly three decades before women were allowed on the fire line. The first woman, whose name was not recorded, reportedly worked with the Bureau of Land Management in Alaska in 1971. (Matthews p. 30)

In 1944 the men published Smoke Jumpers, similar to a college yearbook. The men at Huson published camp papers, Smoke Jumper’s Load Line from March 1943 through September 1944, and Static Line from June 1944 through January 1946.

Director Wiebe reported that even though the men reported diverse religious affiliation or none at all, “about ninety per cent of the men attend church when it is available, especially when they can attend churches of their own choice.” (Gingerich p. 147)

Smoke jumpers attracted the attention of local and national press, recognized for their dangerous service. Margaret Bean, writing in the Spokane, Washington Spokesman Review of June 17, 1945, captured the significance of the work in a story headlined “Conchies Jump Fires”.

Possibly their courage to fight for their convictions, an infinitesimal minority against an overwhelming majority, is responsible for their volunteering for this most daredevil of all jobs, that of the smoke jumper. For certainly it is a rugged job, if there ever was one, both in training and in practice.

The last man transferred out of camp on January 15, 1946.

The men held reunions for many years. Cottrell documented personal stories of sixteen men attending the July 2002 reunion at Hungry Horse, Montana. Matthews recreated the stories of many of the men, drawing on interviews and original documents. (2006)

For a collection of over 30 oral history interviews with firmer CPS smokejumpers, see this online collection from the Archives and Special Collections Department at the University of Montana.

For profiles of sixteen smoke jumpers, see Robert C. Cottrell, Smokejumpers of the Civilian Public Service in World War II: Conscientious Objectors as Firefighters for the National Forest Service. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Publishers, 2006.

For more information on smoke jumpers, see Melvin Gingerich Service for Peace: A History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service. Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee printed by Herald Press, Scottdale, PA 1949 pp. 139-147.

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

See Kevin Grange, “In Good Conscience”, National Parks (Winter 2011) 26-32.

For stories, interviews and photos of CPS men, see Mark Matthews, Smoke Jumping on the Western Fire Line: Conscientious Objectors During World War II. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.