CPS Unit Number 023-01

Camp: 23

Unit ID: 1

Operating agency: AFSC

Opened: 1 1942

Closed: 2 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 286

-

CPS Camp No. 23Coshocton, Ohio.Digital image from Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Miscellaneous Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 23Coshocton, Ohio.Digital image from Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Miscellaneous Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

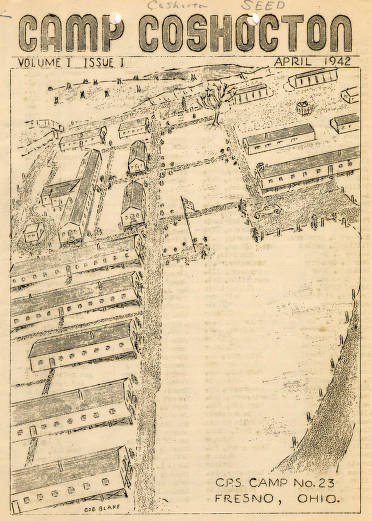

CPS Camp No. 23Seed was a newsletter published by the men at Camp 23 from April 1942 to April 1944.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 23Seed was a newsletter published by the men at Camp 23 from April 1942 to April 1944.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 23, a Soil Conservation Service base camp located in Coshocton, Ohio and operated by the American Friends Service Committee, opened in January 1942 and closed in February 1946. The men staffed the Soil Conservation Service’s experimental station, which was investigating the effects of water on soils.

CPS Camp No. 23, a Soil Conservation Service base camp was located in the foothills of the Appalachians ten miles northeast of the town of Coshocton, Ohio. Coshocton lay seventy-three miles east of Columbus, one hundred and thirty-two miles west of Pittsburgh and ninety-nine miles south of Cleveland.

Directors: Winslow Ames, Lewis Berg, Sumner Mills, Brook Morgan, Ed Peacock, Maurice Webster

The April 1942 issue of the camp newspaper Seed listed around one hundred ten men in the camp from thirteen different states, the largest numbers from New York, Pennsylvania and Illinois. Many of the men entered CPS from urban rather than rural areas.

The men at American Friends Service Committee camps tended to constitute the most religiously diverse group of men, including those who reported no religious affiliation when entering CPS. At Coshocton, the men had reported nearly two dozen different denominational affiliations when entering CPS.

Men in Friends camps and units entered CPS from a variety of occupations with forty-three percent from technical and professional work, twelve percent as students and the same percentage in business management, sales or public administration. At Coshocton, some of the men entered as mathematicians, botanists, had scientific agricultural training, and possessed mechanical and technical aptitudes suited to the work. Men in the Friends camps on average had completed 14.27 years of education, including some with graduate as well as post graduate education. (Sibley and Jacob pp. 171-172)

The men worked in several crews developing new soil conservation methods and applying new practices in agriculture. Seventy-five percent worked with the Hydrologic Research Station “. . . making a thorough study of everything that happens to surface precipitation. For this they set up water-sheds, flumes to measure silt in runoff water. Probably the most complete record of what happens to precipitation and some of the causes for this is obtained from the lysimeters and the instruments operated in connection with them.” Lysimeters measured evaporation and transpiration of rainfall.

To get a large scale view of water runoff and related factors for this area, the Research Station has weirs, flumes, rain gauges, water stage recorders placed at strategic points over some seven thousand acres, known as the Little Mill Creek Water Shed. Over five thousand acres of this are operated on a contract basis with farmer owners and the rest is leased or owned by the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. (Seed April 1942 p. 4)

The men who gathered data from soil tests often traveled long distances on horseback to check communication lines and outlying instruments.

Together, the men assisted the twenty-eight regular employees at the experiment station in investigating the effects of water on soils, conducting experiments testing the best types of soil for different levels of humidity and crop varieties, and analyzed soil samples from all parts of the state. They gathered data, compiled, recorded and interpreted information. In the chemistry labs, CPS men made tests of the moisture and frost content of various soils. Engineers and physicists, some CPS men, made new instruments and worked on hydrologic tests. One CPS man, an outstanding botanist, made the most comprehensive study of plant life in the state of Ohio. CPS mathematicians provided high quality statistical analysis.

Other crews worked on surrounding farms performing soil conservation work. They removed trees, stumps and rocks from cultivated areas in an effort to convert land to pasture or woodland. Then they fenced any revised farm plan. Seasonally, they planted trees. “Approximately 30 men will be needed for planting 100,000 trees at Hills Creek Dam and 40,000 trees on land in the Research area . . .” (Seed p. 4)

Twenty more CPS men performed duties at the camp in the kitchen and camp maintenance. Others worked in the soil office, tool room and garage.

The men worked an eight and a half hour day six days a week.

Since the camp was located in an area populated by Mennonites and Amish people who also were COs, the draft board drew on others to meet quotas of inductees. Community resentment against COs ran high. Each morning as the school bus passed CPS men at work, children “hurled insults” at them. (Goossen p. 39)

The April 1942 Seed reported on assistance provided by the campers to a neighboring farmer due to illness, as well as a cooperative exchange with another farmer to help build a desk in exchange for the gift of an organ to the camp. Both illustrated the point that the men at camp “have found the people of the community ready to respond with mutual helpfulness, ready to respond in turn with cooperation.” (p. 5)

Men in CPS camps, often in isolated areas, were eager for female companionship. Camps located near colleges or universities enjoyed visits by groups of female students. Students from Denison University, not far from Coshocton, arrived for a weekend of dancing and socializing. (Goossen p. 53)

Every morning after breakfast and before the work day began at 7:30, voluntary meditation time was observed, “patterned after the Quaker silent meeting”.

Camp governance addressed rules and regulations, operating on the principle of consensus. However, on routine matters, campers chose a steering committee operating under the camp Articles of Government. “In the true spirit of a representative democracy, two representatives were selected from each section of the several dormitories. These representatives try to sense the options of the groups on matters that are to be brought before the council. . . . The council authorized by the general meeting, acts as a clearinghouse for such phases of camp life as education, recreation, religion, general safety and fire protection, selecting those matters sufficiently important for general camp meeting discussion.” (Seed p. 6)

Coshocton men planned an active educational program. Classes reported in Seed “include Bible study, foreign languages, music, first aid, soil conservation. Additional courses were planned in cooking, photography, electricity, plumbing, philosophy. The program designers hoped to prepare men for “war-rescue work and post-war reconstruction in addition to developing the man’s own personal interests”.

The men experienced an active camp life. Evenings found them in classes, committee meetings, practicing music, using the library (with some 500 volumes), or finding needed items at the camp Co-op Store run by the men. “One of our campers, Darwin Nelson, M.D. holds medical consultation (free, of course) in the infirmary for a half-hour every evening.” Two experienced barbers cut hair in the late evening for a small fee. Late night bull-sessions on pacifist issues surrounding work and living occurred regularly.

Saturday nights varied with shows in the recreation building—music, skits, movies. Among the campers were an opera singer, a concert violinist, and a swing drummer.

The men published Seed on a bi-monthly basis beginning in April 1942 and ending in March-April 1944.

Early on the men published a camp paper called Common Ground, a title used at several other CPS camps as well (No. 6 at Lagro, Indiana, No. 26 at Alexian Brothers Hospital in Chicago, No. 37 at Coleville, California, and No. 42 at Wellston, Michigan).

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

For stories from men who, as COs, walked to a different drummer during World War II, see Mary R. Hopkins, Editor, Men of Peace: World War II Conscientious Objectors. Caye Caulker, Belize: Producciones de le Hamaca, 2010, F. Evert Bartholomew, pp. 73-78; Edwin Stephenson, pp. 56-72.

For general information on CPS camps see Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. Intercourse, PA: Good Books 1990.

Seed Vol. 1 Issue 1 (April 1942); No. 16 (March-April 1944) in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Section 3, Box 6.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-1947. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952, Chapter IX The Schooling of Peacemakers pp. 166-199.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database