CPS Unit Number 111-01

Camp: 111

Unit ID: 1

Operating agency: SSS

Opened: 7 1943

Closed: 2 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 364

-

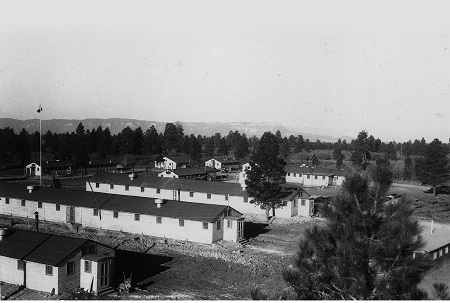

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos Colorado.Camp looking to southwest; Mesa Verde Park, site of ancient cliff dwellings, in distance.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos Colorado.Camp looking to southwest; Mesa Verde Park, site of ancient cliff dwellings, in distance.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved. -

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos Colorado.Early excavation work at damsite, July 1943.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.July 1943

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos Colorado.Early excavation work at damsite, July 1943.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.July 1943 -

CPS Camp No. 111Mancos, Colorado.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.

CPS Camp No. 111Mancos, Colorado.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved. -

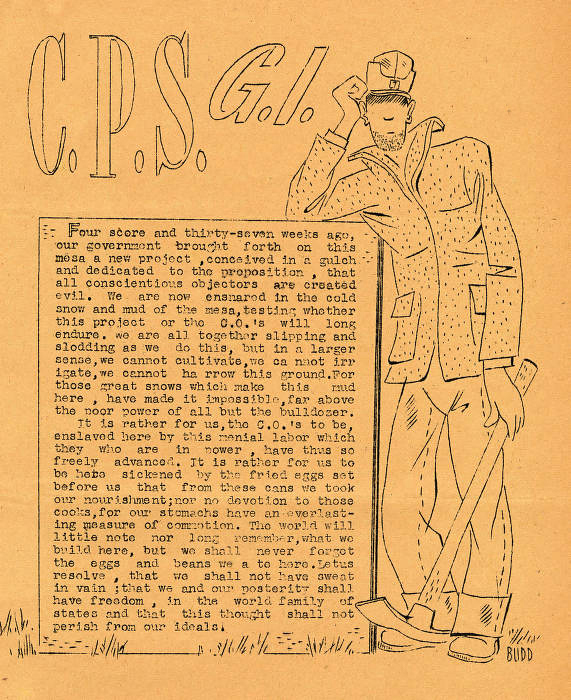

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos, ColoradoC.P.S. G.I. cartoonSubmitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, via email on May 29, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos, ColoradoC.P.S. G.I. cartoonSubmitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, via email on May 29, 2012 -

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos, ColoradoKenny Whitson and Budd Steinhilber at Camp 111Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on June 2, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos, ColoradoKenny Whitson and Budd Steinhilber at Camp 111Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on June 2, 2012 -

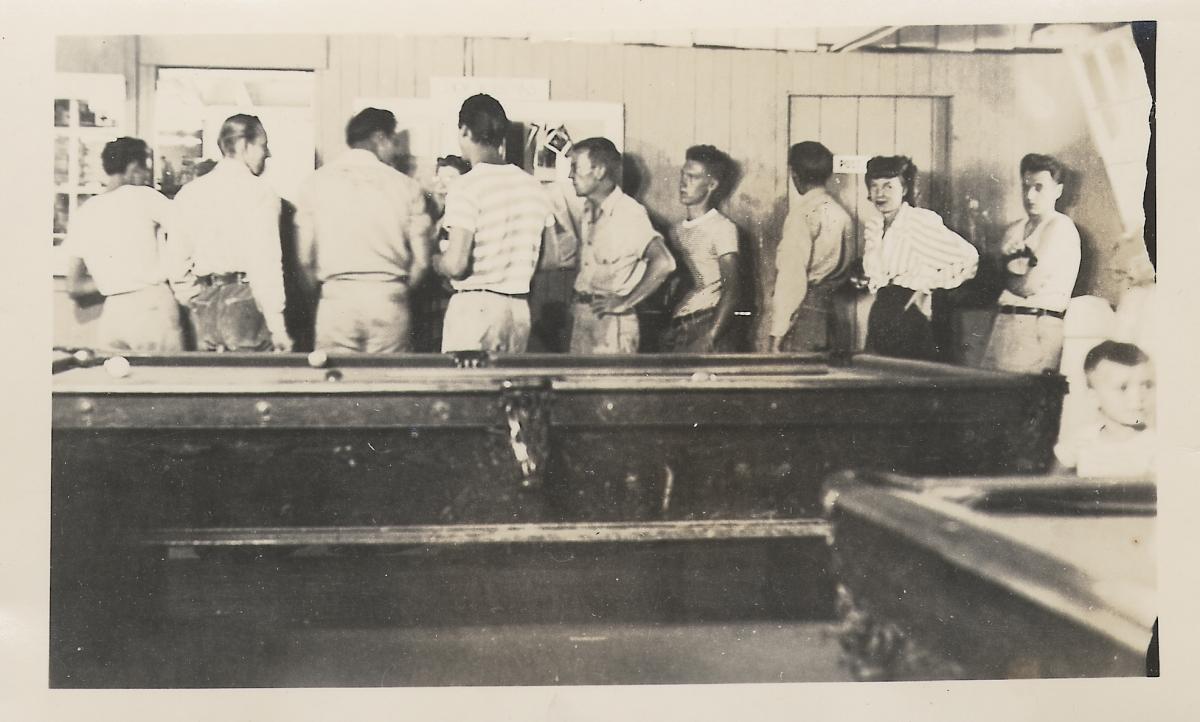

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos, ColoradoLineup in the Rec. Hall waiting for the Co-op window to open. Budd Steinhilber is second from the left. 1945.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on June 2, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos, ColoradoLineup in the Rec. Hall waiting for the Co-op window to open. Budd Steinhilber is second from the left. 1945.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on June 2, 2012 -

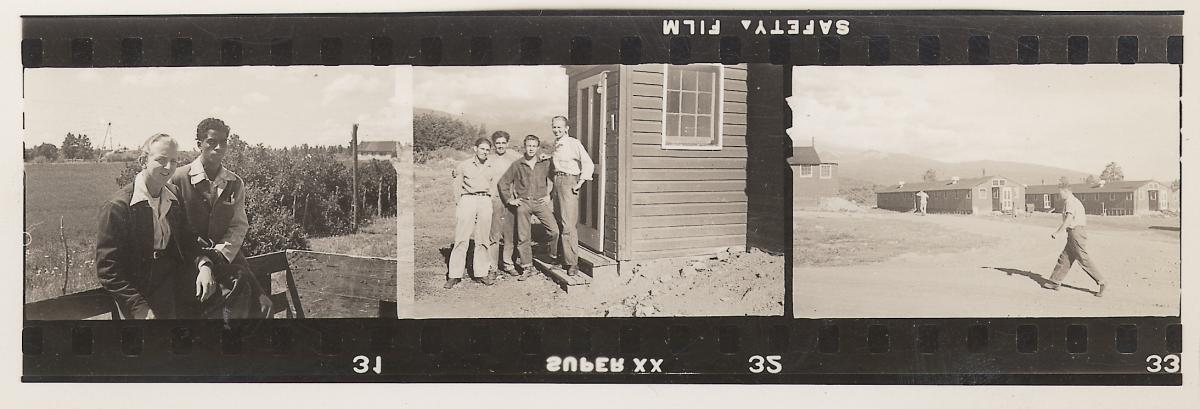

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos, ColoradoMancos Camp. Budd Steinhilber is on the far left in the picture on the left and on the far right in the middle picture.Photo submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on June 2, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111, Mancos, ColoradoMancos Camp. Budd Steinhilber is on the far left in the picture on the left and on the far right in the middle picture.Photo submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on June 2, 2012 -

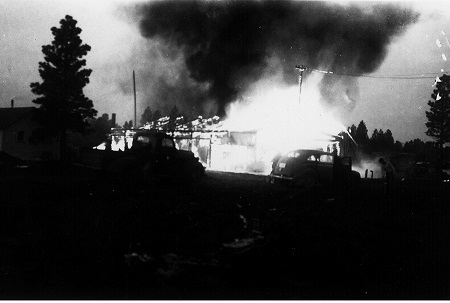

CPS Camp No. 111The night the machine shop burned down.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111The night the machine shop burned down.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012 -

CPS Camp No. 111Dormitories at CPS Camp No. 111Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 20121944

CPS Camp No. 111Dormitories at CPS Camp No. 111Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 20121944 -

CPS Camp No. 111Elevation 8,500 ft. Mt. Hesperus peaking over right horizon.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111Elevation 8,500 ft. Mt. Hesperus peaking over right horizon.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012 -

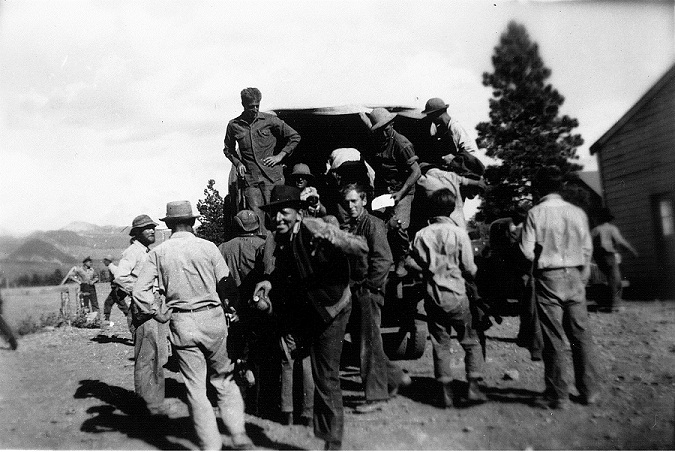

CPS Camp No. 111Loading up trucks to head back to the project. [John] Budd Steinhilber in foreground. Man behind Budd, George Barbarow[?]. Far left is Forrest Leever.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111Loading up trucks to head back to the project. [John] Budd Steinhilber in foreground. Man behind Budd, George Barbarow[?]. Far left is Forrest Leever.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012 -

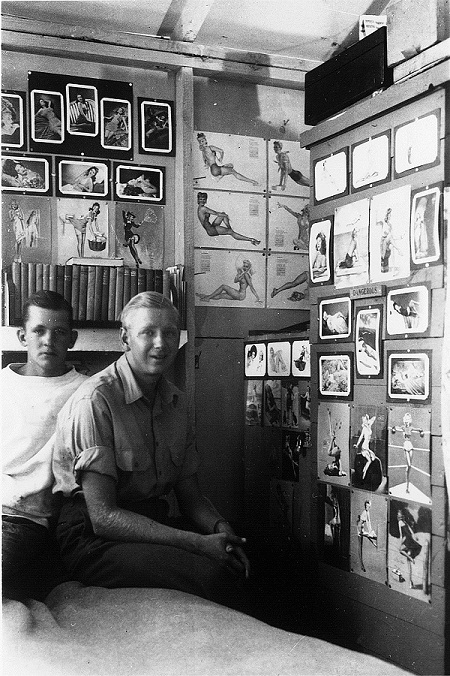

CPS Camp No. 111Bunk area of Lloyd "Tex" McManus (at left).Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111Bunk area of Lloyd "Tex" McManus (at left).Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012 -

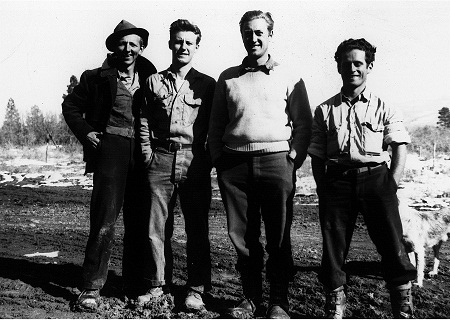

CPS Camp No. 111Budd Steinhilber, Carl Nocke, Carl Huber, and Trent May. All four had been in Petersburg before transfer to Mancos Camp 111.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111Budd Steinhilber, Carl Nocke, Carl Huber, and Trent May. All four had been in Petersburg before transfer to Mancos Camp 111.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012 -

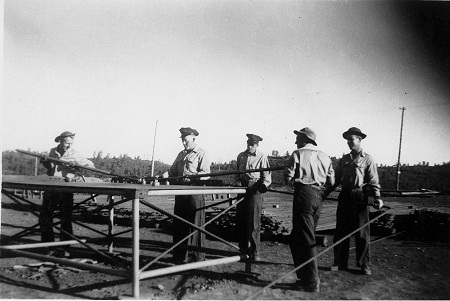

CPS Camp No. 111Steel re-bar bending crew. Budd Steinhilber is doing the heavy work on the bending lever (left), while the Amburgy brothers (Wayne and Claude) in the captain's hats, and others look on.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111Steel re-bar bending crew. Budd Steinhilber is doing the heavy work on the bending lever (left), while the Amburgy brothers (Wayne and Claude) in the captain's hats, and others look on.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012 -

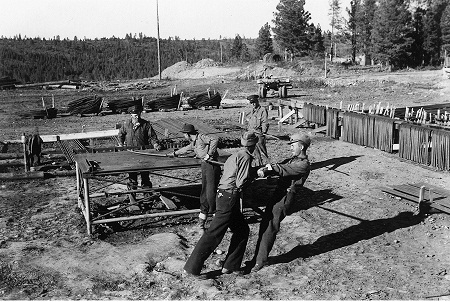

CPS Camp No. 111More reinforcing bar bending. This assignment lasted for months.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111More reinforcing bar bending. This assignment lasted for months.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012 -

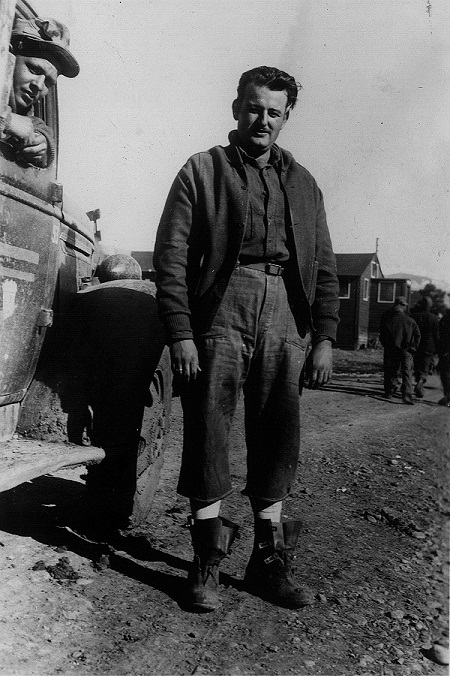

CPS Camp No. 111Mack Shellabarger demonstrates that government issue pants are rarely tailored for fine fit. Lloyd "Tex" McManus sticking his head out truck window.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111Mack Shellabarger demonstrates that government issue pants are rarely tailored for fine fit. Lloyd "Tex" McManus sticking his head out truck window.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012 -

CPS Camp No. 111Heading back to work through the snow after lunch break.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 20121945

CPS Camp No. 111Heading back to work through the snow after lunch break.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 20121945 -

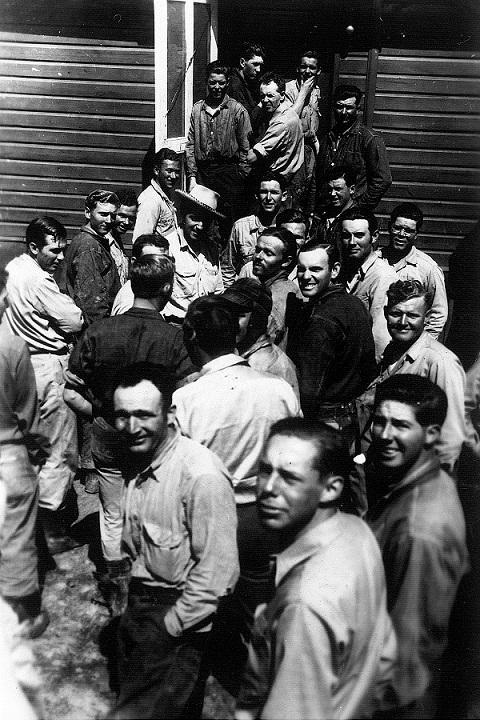

CPS Camp No. 111Waiting for mess to open for lunch. Foreground left: Hank Turek (Norman's old penmate). Center: Hank Baine (wide brim), just opposite him is Orville Wellman with the goatee.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111Waiting for mess to open for lunch. Foreground left: Hank Turek (Norman's old penmate). Center: Hank Baine (wide brim), just opposite him is Orville Wellman with the goatee.Submitted by Budd Steinhilber's daughter, Julie, on August 7, 2012

CPS Camp No. 111, a Bureau of Reclamation camp in Mancos, Colorado operated by the Selective Service System, opened in July 1943 and closed in February 1946. In this first government operated camp, the men performed work utilizing a variety of skills to construct a dam, clear a reservoir site, and improve irrigation systems to open ten thousand acres of farm land.

Mancos was the first of three government operated CPS camps, located at Jackson Gulch, four miles up a twisting dirt road from Mancos, Colorado in an isolated part of the state. Not far from the Four Corners area in southwest Colorado, the town lay in the Mancos River Valley at nearly seven thousand feet elevation.

Director: Charles Thomas

On July 1, 1943, eighty-one men transferred into the camp, some by their own choice and others without choice. If an assignee elected to serve at a “non-religious” camp, he was sent to Mancos. By 1945, one hundred and fifty-two men made up the camp.

With respect to religious affiliation, the men at Mancos reported a diversity of religious affiliation when entering CPS, with a significant number reporting no religious affiliation.

The work required a variety of skills, including the use of heavy machinery. The men constructed an earth dam, cleared a reservoir site and improved irrigation systems to open ten thousand acres of farm land.

The work had no connection with the war effort. Further, the work standards were more lenient than at church-related camps. The engineer director appeared friendly, eager to secure good project work, and willing to grant privileges within his power.

Men had originally requested an alternative to religiously-administered camps believing that they would enjoy more freedoms in the government operated camps. They further sought pay for work in addition to work that would more readily utilize their skills.

When the National Service Board finally urged Selective Service to operate one or more government camps, they did so with three main provisos:

- The men would receive pay in addition to maintenance

- The projects would not have military significance

- Men would have opportunity to use skills other than manual labor

Unfortunately, General Hershey did not approve pay for the men at the government camps since no CO in CPS received a wage for his labor. However, the men reported that the food was superior to food at other base camps with respect to both quality and quantity. The food budget at the Army garrison level was 60 cents per man, or about 50 percent higher than the amount budgeted for CPS camps.

The government paid for the men’s maintenance, medical and dental care, and clothing in addition to providing an allowance of $5.00 per month.

The men published a camp paper Action from July 1943 to June 1944. Men at CPS Camp No. 32 in Campton, New Hampshire, as well as men at CPS Camp No. 135 at Germfask, Michigan, published camp papers with the same title. Also, from November 1943 to December 1945, the men published a paper C.P.S. G.I. Men at CPS Camp No. 46 at Big Flats, New York, used the same title for a camp paper.

Tom Vaughan, researching this camp, observed "It interested me that almost nobody knew about the CPS experience in the Mancos Valley, although the community's public library was founded on the quantity of books in the CPS camp library that were dontated to the community when the camp disbanded". (Tom Vaughan, July 10, 2011).

Selective Service, in spite of the expressed secularism of some men, agreed with the Federal Council of Churches to appoint a full time chaplain. Any group of assignees, such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses, Mennonites or Disciples of Christ, held services as desired. Christian Kehl, a CPS assignee and chaplain available when the camp opened, was later replaced by visiting chaplains, after he had a policy disagreement with the camp director.

In the camp, Selective Service retained its full authority and control over policy, and when men challenged this underlying principle, camp authorities responded with immediate action to maintain control in a sometimes abrupt or arbitrary manner. This did not set well with those who distrusted the government or those “chronic objectors” to government authority. Some men had been moved into government camps against their will for the following reasons:

- Punishment for insubordination

- Unsatisfactory work

- Failure to choose service uner a religious agency

- Medical observation (Sibley and Jacob, p. 249)

Colonel Franklin McLean of Selective Service noted the deteriorating relations in between assignees and camp officials in The Reporter Supplement, Nov. 1, 1944, a publication of the National Service Board of Religious Objectors.

Inclined to judge men by their attitude toward the job and the way the work was done rather than by what they said or professed to be[,] they [the administrative staff] could not understand some of the people with whom they had to deal. Unfavorable opinions as to sincerity and motives were formed, which, unfortunately, were extended to persons entirely blameless. Confusion and antagonism were deliberately fostered and spread by certain individuals who claimed to be pacifists but who employed all methods of force and coercion except, possibly, physical violence. Various measures were adopted by the camp administration in an effort to correct the situation. Mistakes were made at times and there were errors in judgment, the result being that in some instances, the majority of assignees, who were sincere and well intentioned, were the ones who really suffered. . . . [T]here still remains as a result of these activities a lack of confidence and a certain amount of distrust between assignees and staff that it will be extremely difficult to overcome. (in Sibley and Jacob pp. 249-50)

Matters intensified as the men felt a deep sense of injustice over the government’s refusal to pay for compulsory labor, to give fair consideration to some men who had requested medical discharge, and to permit the opportunity to transfer to special service projects available to those in the church directed camps.

Camp officials tried two approaches. First, they put the sick to work, which worked in some cases. The men vigorously objected that some men were to have been under medical observation in preparation for medical discharge or were not given a thorough medical exam on entry, and protested the lack of medical care to Washington. When medical examiners appeared, their review produced a few discharges. However, the examiners generally concluded that not all of the men on sick leave were ill but rather were apparently avoiding work. The FBI was called in to collect evidence for charges against the latter. Upon arrival, the agent challenged the right of administration to overrule sick status, particularly when confirmed by a local doctor. Colonel McLean on a semi-annual inspection trip discovered that a man for whom the director had prescribed “fresh air and light exercise” on the project had actually collapsed several times from heart attack at the high altitude. McLean immediately arranged for the man to return home with an attendant. These incidents resulted in a review of medical examinations which might result in reclassification, and a loosening of practices compelling sick men to work.

The second approach attempted to isolate “the uncooperative”. Since the only privileges that could be taken away were furloughs, that action had little effect. The threat of legal prosecution for organized work slowdowns meant the administration would have to go through lengthy proceedings. Thus the administration chose to place men on “special assignments” apart from the main camp. Eventually, the government decided to add a third government camp at Germfask in northern Michigan and place “the uncooperative” men there.

Sibley and Jacob noted that authority, when joined in conflict with conscience, is no match with skilled resistance. Some observed that the experience took a toll on COs, who appeared to have lost their vision of protest against war in the face of protesting the immediate situations in camp. The frustration and antagonism continued at Mancos until the camp was demobilized in February 1946.

The compromises with government required to forge CPS in a time of national crisis, did not always satisfy many of the men the program sought to protect. The American Friends Service Committee withdrew from the program in March 1946, frustrated with the punitive aspects of the program and the struggles and objections of men in their camps and units. One Mennonite CO who had served three years in CPS observed,

Why not say—this was the best thing that could be worked out on short notice, with a government having no experience with alternate service and afraid to move, and worked out within the framework of adverse public opinion. In trying to improve it we have run up against the wall of government conservatism and lack of interest. Then when we have said this, we should say it again. (Paul Albrecht to Albert Gaeddert, 23 January, 1946 in Gaeddert Papers, Mennonite Library and Archives and quoted in Goossen, p. 27-28)

See Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Mennonite Library and Archives at Bethel College, North Newton, KS.

http://www.bethelks.edu/mla/index.php

See Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952, Chapter XI: Government Camps pp. 242-256.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.

See Tom Vaughan's work at: http://swcenter.fortlewis.edu

At the Center of Southwest Studies, Fort Lewis College, under WW II finding aid:

Collection M 189: *Civilian Public Service in Colorado printed materials.*

1 document case and 1 records box. Printed materials related to the

Civilian Public Service (CPS) camp #111, 1943-1946, at Jackson Gulch, four

miles up a twisting dirt road from Mancos, Colorado, 1943-1946. This was

one of 151 CPS work sites created in the U.S. during World War II, and one

of only 4 such camps in Colorado. According to Tom Vaughan, this camp "took

up the work of an earlier Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp at the same

location.